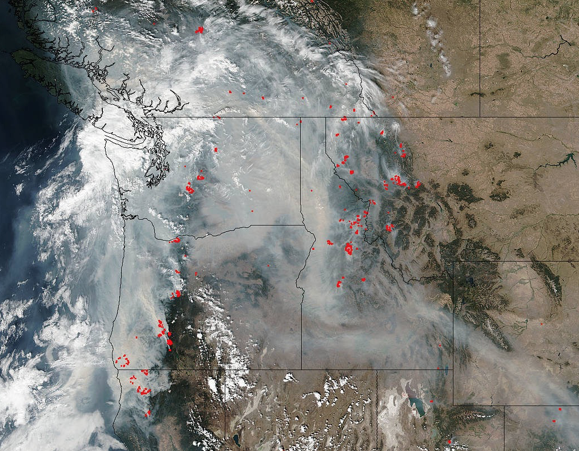

NASA satellite image showing smoke over of the Northwest as of Sept. 5.

By Jack Williams

This past winter was a wet one where I live in southwest Oregon. “Atmospheric rivers” brought record rain and snow storms to the region. We were not alone. Rains and snows drenched California and built big snowpacks in the Sierra. Forecasts called for a relatively mild wildfire season due to all the moisture.

But snowpacks melted early and record heat built up across much of the West. We now find ourselves in the midst of heat, wildfires, smoke and ash. As of September 8, 2017, the National Interagency Fire Center reports 82 large, active wildfires in the West currently burning on nearly 1.5 million acres with a total of just over 8 million acres burned so far this year. Our neighbors to the north in British Columbia are suffering their worst wildfire season in recorded history with more than 140 active fires, nearly 3 million acres burned and thousands evacuated from their homes. And, this wildfire season appears far from over.

So, what happened? How does such a wet winter translate to an uncontrolled wildfire season just six months later?

Our July was hot and dry. Not a single day of measurable rain. Then August made July seem mild. We had multiple days above 110 degrees here in Southwest Oregon. Montana, Washington and other western states were in record heat as well.

The reality is that we are getting hotter each year. Recall that 2016 set a global record for heat. It broke the previous records set in 2015. More heat means earlier snowpack melt, greater evapotransporation from plants, earlier forest drying, and hot summers.

Wildfires in the West are increasing. During the past decade, the average annual acreage burned in the U.S. has increased to 5.5 million acres. This year is more than 8 million acres and counting. But how much of this increase is due to past wildfire suppression practices, or simply weather variability, as compared to climate change? In a paper published last year in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, scientists from the University of Idaho and Columbia University determined that since the 1970s, climate change has accounted for more than half the increase in forest drying which approximately doubled the extent of forest fires in the U.S. beyond that expected from natural climate variability alone between 1984 and 2015.

That is huge and beyond our ability to address through changes in forest management.

Another factor contributing to increasing western wildfire is the greater number of dead trees in our forests. The U.S. Forest Service estimates that there are about 6.3 billion dead trees in western forests as a result of some combination of drought and insect pests. Both factors have a strong climate connection. For pine and bark beetles, warmer winters means less overwintering mortality and faster generation time, which signals greater population sizes for forest insect pests. Extreme cold knocks back these pine and bark beetles and we just don’t see those cold spells like we used to. The U.S. Forest Service says that since 2010, massive infestations of beetles have been the leading cause of tree mortality in the West.

That means it’s a relatively simple equation to describe our future. Warmer temperatures combine with drier forests and longer fire seasons to create more and bigger wildfires in the West. It’s something that both fish and people will have to deal with. A good start would be to recognize what is driving the problem—climate change—and start dealing with it head-on. That is a call to action on national policy. In the meantime, let’s continue to do what we do best at TU: protect the best remaining habitats, reconnect fragmented habitats, and restore our stream channels and riparian areas. This not only will increase the ability of trout and salmon to survive the extreme and rapid pace of environmental change that now confronts us, but also help human communities cope with drought, floods and wildfires.

Climate change is a huge problem whether policymakers choose to address it or not. But we can take specific steps today that lead to a better tomorrow.

Jack Williams is TU’s Senior Scientist who lives in the Rogue River Valley.