By Eric Crawford

If only it was as simple as an adipose fin.

The presence of an adipose fin is universally recognized as the mark. An individual with an adipose fin is, with a few exceptions, considered a wild steelhead. On the other hand, those marked, clipped, or ad-intact fish, they are the hatchery ones. Although it is but a small mark, the presence of the fleshy fin tells more about the steelhead’s story than you think.

The adipose fin tells us about where the fish was raised. In nature, or in a raceway. It also often signifies whether we can retain the fish or not. And, if you are a biologist, it will give you some insight into the diversity of the animal.

One reason we appreciate the diversity is that it allows us to fish for steelhead almost the entire year, depending on the region and watershed. Another reason is because of the resilience it conveys to the species.

There are a number of examples of the amazing resilience of wild steelhead, but none more so than the Toutle River. Take for example Washington’s North Fork Toutle River that was absolutely destroyed during the 1980 eruption of Mt. St. Helens, yet only a half dozen years later the Toutle River experienced one of the largest returns of wild steelhead in the lower Columbia. By 2014 the population had recovered to the point where it was designated as a wild steelhead gene bank by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Just how does that kind of turnaround happen? Diversity and resilience. The hallmarks of wild steelhead.

Let’s start with diversity. Steelhead display more diversity in life histories than any other salmon species, and it’s not really close. A life history is what a steelhead does to complete its life cycle and reach maturation. For instance, steelhead may rear in freshwater for one to five years and may spend less than one year and up to five consecutive years in the ocean before returning as adults. So, a steelhead that spends one year in freshwater and one year in saltwater is one life history, while a steelhead that spends one year in freshwater and two years in the ocean is another life history. And so on with the various combinations.

Further, there are both winter and summer runs of steelhead; some steelhead spawn more than once, and some steelhead offspring never go to the ocean and instead remain in freshwater where they mature as rainbow trout. Given all the possibilities, it is not surprising that steelhead may display up to 38 life histories within a single population, compared to perhaps a dozen for chinook salmon and one or two for species like pink salmon.

That diversity is what makes steelhead stand out from the other salmon species.

That staggering diversity conveys a very important benefit to steelhead. The diversity helps spread risk, much like a financial portfolio that includes an array of financial assets, like stocks, bonds and commodities. Some of those assets perform better than others over time, which is why a diverse portfolio is important: it helps stabilize performance.

The same is true with steelhead life histories. Some life histories survive better in certain conditions and years than others and different life histories tend to use different parts of a watershed at different times. Ultimately then, diversity helps reduce annual variability in run sizes and improves the resilience of the population as a whole.

For instance, pink salmon have very few life histories and they nearly all migrate to the ocean at a similar time in life. This is a very risky proposition, much like investing only in stocks. If you have a great ocean year, the fish do really well. But if one bad event hits those fish at any point in their life, the population is more prone to crashing.

Steelhead on the other hand don’t put all their eggs into one basket. They spread the risk. Smolts of different ages are in the ocean at all times and adults are returning at different ages and places. This is one reason wild steelhead were able to rebound so quickly after a dramatic event like the eruption of Mt. St. Helens.

Consider steelhead diversity in Asotin Creek, a small tributary of the Snake River in eastern Washington. Overshadowed by its neighbor the Grande Ronde River, Asotin Creek supports a robust summer run of wild steelhead. Unlike the Grande Ronde however, Asotin Creek is closed to fishing and serves as a refuge for wild steelhead in the Snake River basin. It is also one of NOAA’s intensively monitored watershed, which means that Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) and NOAA have closely researched the population and its habitat.

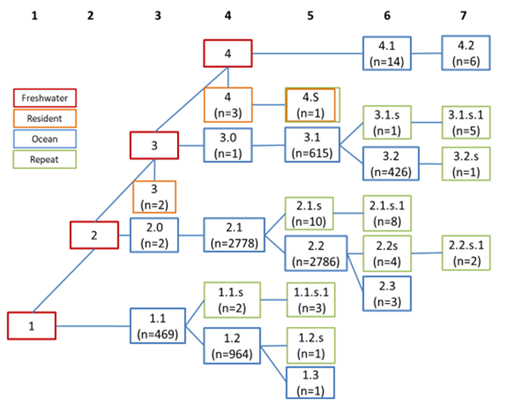

To illustrate the diversity in life histories we borrowed a diagram a WDFW annual report on steelhead (2002-053-00: Project Summary – CBFish.org).

Confusing? Yes! This is diversity and resilience in its purest numerical form. Data came largely from scale samples. Asotin Creek has a weir and many juveniles are implanted with Passive Integrated Transponder (PIT) tags. Scales are taken from adults captured at the weirs, which provides data on time spent at sea and in freshwater, and PIT tag data helps provide additional data on the timing and movements of juveniles.

The figure displays the different life histories adopted by steelhead. The top row of numbers, ranging from 1 through 7, refers to the total age of each fish sampled. On the left vertical axis there are four red boxes labeled 1 through 4 that specify smolt age. For instance, the number one box indicates a fish that spent one year in freshwater and smolted at age 1. It also includes the number of years spent at sea, represented by the blue boxes, which range from one year at sea up to three years at sea. We then have the orange box, which tells us the age of fish that matured as residents in freshwater without ever going to the ocean, and then the yellow boxes, which display fish that were repeat spawners.

You will notice each box has a number, like 2.1, and below that is another number by the letter “n.” The number before the decimal is the age at smolting and the number after is the time spent in salt. So 2.1 refers to a 2-year old smolt that spent a single year in the ocean.

The “n” is the number of fish that displayed that specific life history. The blue boxes refer to the different life histories of first-time spawning adult steelhead. The yellow boxes refer to the different life histories of repeat spawners and the red/orange box refers to the age of resident rainbow trout. What you will notice is total age appears older than the individual years spent in freshwater and saltwater. This is because anadromous summer steelhead enter freshwater in summer and don’t spawn until the following spring, so this diagram adds in those missing months.

Overall, there are a total of 25 boxes, or 25 life histories (which by the way is comparable to the number of life histories documented in a small coastal stream in Washington). Among those, most returning adults were four to five years old. The two most common life histories were 2.1 and 2.2 steelhead, which spent two years in freshwater and the one or two years in the ocean, respectively. The next most frequent life history were one year old smolts that spent either 1 year (1.1) or two years (1.2) at sea. The least common were the 7-year-old fish and the handful of resident rainbows that were captured matured at three and four years of age.

The story is quite different for steelhead without the adipose. All the fish reared in a hatchery are released at the same time. So there is only one smolt age. And, most adults return at similar ages, usually after one or two years in the ocean.

By my count that is one adipose fin and two dozen options relative to a handful of life histories and no adipose fin for the hatchery fish.

Of course, it isn’t really about the adipose fin. It’s about their environment and genetics. Wild steelhead rear and spawn in highly variable environments differing in everything from water temperature to geology. For a fish to persist it must adapt to those local conditions and because the conditions vary, so do the solutions for the fish (e.g., their life histories).

The diversity in Asotin Creek steelhead perpetuates their ability to survive in an otherwise very difficult situation. The adults and juveniles must pass through eight dams in the main-stem Snake and Columbia Rivers. While the population has struggled in recent years along with other salmon and steelhead in the Snake River basin, it has not blinked out. It is not near extinction. And like the Toutle River, that should not surprise us.

In fact, Asotin Creek steelhead provides hope. Scientists working in the watershed are collecting long-term data on adult and juvenile abundance and diversity. Those types of data sets are rare. Kudos to all that have worked so hard to make that data set a reality. Many of us at Wild Steelheaders United have spent time in the field for various purposes, so we know the level of commitment that it takes to collect such data.

They are also experimenting with different habitat restoration actions. This information will be invaluable to better understanding how fish respond to climate change and other changes in our environment. As importantly, it underscores the extent of diversity in wild steelhead, and highlights the need to conserve this diversity as a means of conserving the species and the fisheries steelhead provide.

At the end of the day, we love wild steelhead not because they have an adipose fin. We love them because they are so diverse and resilient. We love them because that diversity generally conveys longer fishing seasons than for other species. And because we never know whether it will be an 18-inch or 30-pound fish on the end of our line.

Simply, we love steelhead.

Eric Crawford is the north Idaho field coordinator for TU’s Sportsmen’s Conservation Project.