Restoring a piece of fly fishing history

New bamboo fly rods often command hefty prices and long waiting lists appropriately reflecting the time and craftsmanship put into them, but there was a time when even anglers of modest means could fly fish with bamboo.

Mass-produced bamboo fly rods from the 1920s through the 1950s are known as “blue collar” bamboo, made by companies that might be better known for their baitcasting reels and lures than their fly rods. Many of these rods could be purchased at the local hardware store at prices that put fly fishing within reach of hard-working people on limited budgets, helping to usher in the outdoor recreation boom of that era and helping to dispel the myth that fly fishing was only for the wealthy.

Even today, those old rods are abundantly available at prices comparable to new midlevel and budget graphite rods, and even cheaper if they need refinishing or a full restoration. With some glue, thread, and elbow grease, they can often be restored to a fishable condition at little cost.

Mass Produced in America

Back then, before fiberglass and later graphite rods hit the market, almost all fly rods were made of split Tonkin bamboo, except for a few experiments with steel rods. South Bend, Shakespeare, Union Hardware, Winchester, Montague, Granger, Horrocks-Ibbotson, Phillipson, Heddon, and Wright & McGill were some of the makers of what are now considered blue collar bamboo fly rods.

While the rods were mass-produced and didn’t use the same top-end materials – and sometimes fewer guides or intermediate wraps – than found in more expensive and finely, individually crafted rods like a Payne, Leonard, Dickerson or Garrison, they were American-made by hand by shop workers and often designed or supervised by the top rod makers of the era.

Wes Jordan, who later designed fly rods for Orvis, designed the rods for South Bend (in South Bend, Indiana) which was probably better known for its “level-wind” baitcasting reel. It was one of his rods that spurred my interest in blue collar bamboo when I bought a South Bend bamboo fly rod in poor condition for $25 from a fellow member at the Ann Arbor Trout Unlimited Holiday Gear Swap in December.

Evaluating the South Bend

The rod had all the ferrules, and they fit snugly and “popped” when pulled apart, but the glue had dried out on the butt section ferrule. The cork grip and reel seat looked good. It had two tips, taped up with masking tape, but one was a couple inches short and missing a tip-top, having broken off. Multiple guides were missing and the ones that were present had a bulky home-epoxy winding holding them in place. Finally, every section was delaminated, meaning the six strips of bamboo glued together to form the rod were dried out and separated.

It would need to be completely restored, but if I could restore this rod to a fishable condition, then along the way I would learn all the basic steps of both rod restoration and building a rod from a blank. And at the end, I’d either have a fishable bamboo fly rod for less than $50 or I’d have a good-looking wall decoration for my fly-tying room. And in its condition, I wouldn’t feel too bad about disfiguring an antique if I messed up the restoration; there wasn’t much left to damage.

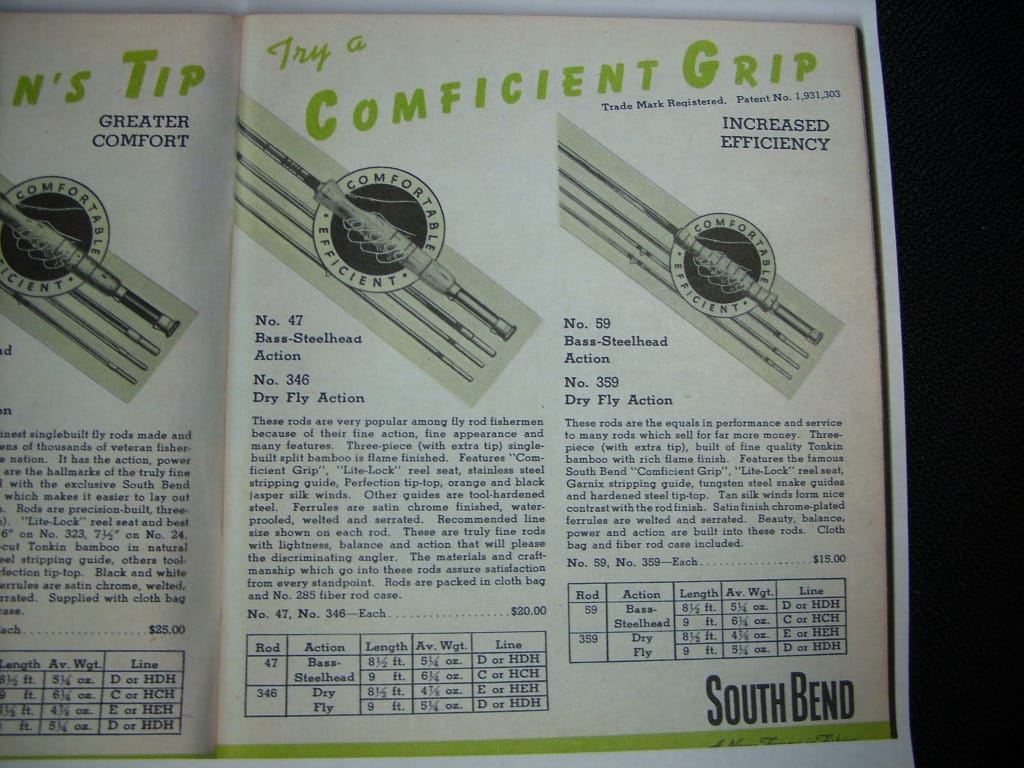

I wanted to know as much as I could about the rod model, though. The Classic Fly Rod Forum provided the answers, from multiple threads on South Bend rods to actual images of their catalogs from the era. The script on the butt section read “359-8 1/2.” It was a South Bend 359, made with a “Dry Fly Action” and a “Comficient” cork grip. Wes Jordan had left South Bend for Orvis in 1939, the year that the South Bend Model 359 debuted.

Judging by the hardware and the underlying tan thread color and matching catalog descriptions, I estimated that it was probably made between 1948 and 1950. In those years, the 8 ½ -foot Model 359 was rated for E and HEH or HDH line (HEH in 1949, HDH in 1948 and 1950), equivalent to a 5wt (E and HEH) or 6wt DT (HDH) today. It would have retailed for $15 – a little under $200 today.

Restoration

Following video tutorials from Proof Fly Fishing, I ordered new guides, built a rod-winding jig from scrap lumber and glued strips of felt to the “V’ notches that would cradle the rod using adhesive felt from the Outdoor Life Book Club out of my grandpa’s old rifle cleaning kit. I set it up on my fly tying bench.

Next, I stripped the rod by cutting off all the remaining guides and winding, but marking the side of the rod the guides went on with tape on the ferrule and mapping the guide spacing on a sheet of paper. I glued the delaminated sections back together with Titebond III wood glue applied with toothpicks, and spiral-wrapped them with old backing. After the glue dried, I sanded off the thread, glue, and varnish, careful to maintain the hexagonal edges. Then I re-varnished the rod by wiping on multiple coats of marine spar and letting it dry. I glued back on the loose ferrule and a new tip-top.

Finally, I wound on the new hook keeper, stripping guide and snake guides, using a yellow and black silk jasper thread from a fly tying kit my uncle had given me of his dad’s a couple years ago.

Here, I made a mistake.

Rather than use a color preserver, I tried the varnish on the thread on a broken tip section of bamboo, and I liked how it turned the yellow and black jasper thread to bronze and black, which matched the metal reel seat well. However, when I varnished the thread wraps directly on the rod, they came out much darker. Though it still matches the reel seat and looks good on the rod as dark brown and black thread, it obscured the cool yellow and black jasper thread pattern more than I wanted.

Casting

The final varnish dry, my restored rod was ready to try out on the lawn. With an unseasonably warm New Year’s Day and no snow in my backyard, I rigged up a matching dark brown Martin 62 vintage reel with Scientific Anglers Amplitude 5WF line and a 7 ½ foot leader. I tied on a No. 14 Royal Wulff, which felt appropriate.

And I cast.

It didn’t take long to find the sweet spot, and I was able to cast the Royal Wulff crisply and accurately at the distances I expect to fish for brook trout on smaller streams and rivers in Michigan when most of my favorite streams open at the end of April.

Overall, I was happy with the restoration. I certainly need more practice on all phases of the process, but it was a good first attempt. I wouldn’t sell it, but I’ll fish it.

Fly Fishing is for Everyone

Throughout the restoration, I couldn’t help but wonder about who fished the rod before me, and the experiences it had on the stream. What fish did it catch, what flies did it cast, and – more importantly – what memories did it create for its anglers in the decades since it was made?

To me, blue collar bamboo represents the egalitarianism of fly fishing more than anything else: a symbol often associated with the more snobbish aspects of the pursuit but made for people to enjoy the outdoors on their day off from the mines, or in a factory, upon returning from the World Wars of the first half of the last century or the Great Depression in between them, when all that a day on the stream can offer was needed most.

With a little elbow grease, some glue and some thread, today’s anglers can access the aesthetic grace, slow action, and delicate presentation of a bamboo fly rod for not much more cost than the original price that made these rods affordable for anglers several decades ago.

Fly fishing now, as then, is for everyone. Even with bamboo.