Owen Prettyman fishing a small creek while attempting to complete his Utah Cutthroat Slam with a Bonneville cutthroat trout. Daniel A. Ritz photo.

Making memories to last a lifetime in Utah

Daniel Ritz is fishing across the Western United States this summer in an attempt to reach the Master Caster class of the Western Native Trout Challenge, attempting to land each of the 20 native trout species in their historical ranges of the 12 states in the West. You can follow Ritz as he travels across the West by following Trout Unlimited, Orvis, Western Native Trout Challenge and Montana Fly Company on social media using the #WesternTroutChallenge.

In December of 2020, during initial research for another article I was working on focused on the native trout of my home state of Idaho, I began to notice one name seemingly tied to almost every native trout and “slam” project I could find.

Brett Prettyman, based in Salt Lake City, was the outdoor editor of the Salt Lake Tribune for 25 years before becoming a communications director at Trout Unlimited. While working for the Tribune, he became aware of the Wyoming Cutt Slam and began promoting a similar concept in Utah through regular newspaper columns.

After taking the job with TU, Prettyman began championing the concept in Utah with his new voice. He found an ally in Greg Sheehan. Sheehan was the director of the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources at the time and asked Prettyman to help Utah launch what is believed to be the first full partnership between a state and non-profit group on a fishing quest program. The Utah Cutthroat Slam was launched on April, 1, 2016. To say it has been a success would be an understatement.

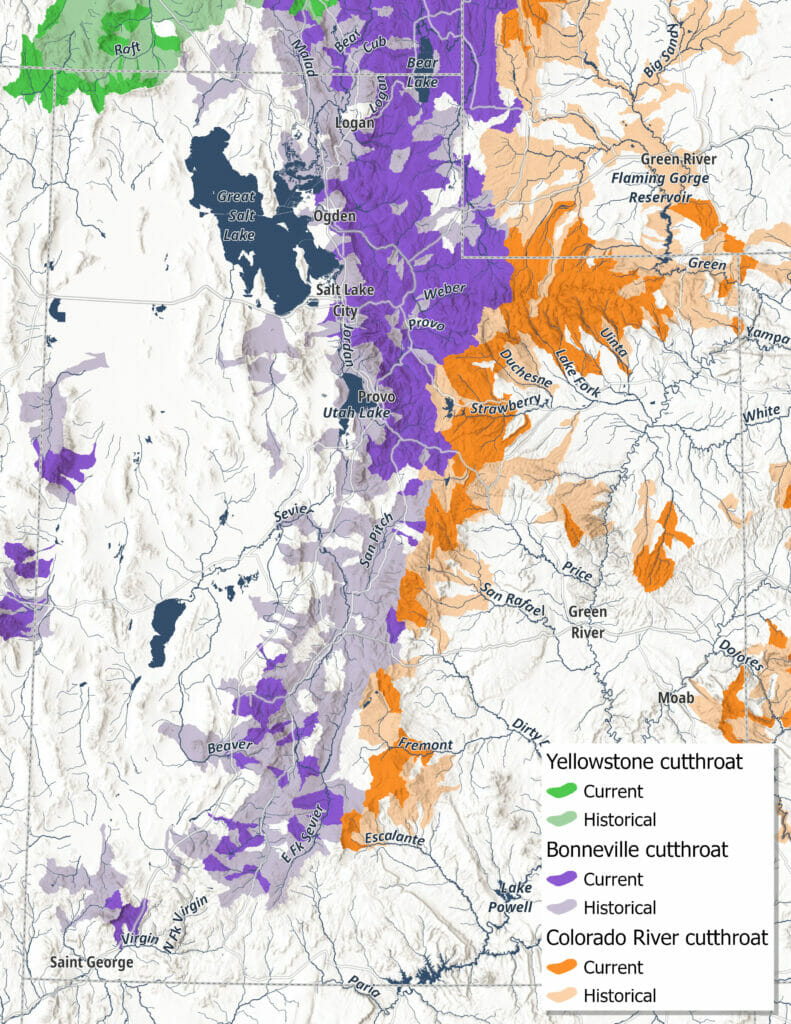

The Utah Cutthroat Slam consists of a challenge to catch the four unique cutthroat trout subspecies in their respective native historical ranges within the state.

“For me,” Prettyman said as we wrapped up some time on the water chasing Bonneville cutthroat, “the goal was not only to educate out-of-state anglers but to help Utahns understand the native fish we have here. Education is the most important part to me. The Slam inspires people to get to new waters. It forces them to get out of that comfort zone we all get in as anglers and try something different.”

Feeling motivated after our conversation I went ahead and ponied up my $20 entry fee and got to work on planning.

Why an entry fee? While neighboring Wyoming—which served as a model for the Utah Cutthroat Slam—doesn’t include an entry fee (excluding a fishing license), Prettyman said both Utah and Trout Unlimited supported charging the fee with and all but $1 from each slam registration going toward native cutthroat conservation work. Once a submitted slam is approved the angler is sent a certificate and medallion acknowledging the accomplishment.

Due to concerns about water levels and temperature, my own Utah Cutthroat Slam adventure began in early May. Deep in the Raft River Mountains of northwestern Utah an isolated population of Yellowstone cutthroat trout still exists.

Long, expensive story short, my initial effort was a failure to launch. Rains forced me to evacuate before becoming trapped in the slick clay and impassable backcountry. All in all, this wasn’t an entirely terrible event considering the stream I had brought my family too barely held any water anyway, even in early May.

I did manage to get into my first Yellowstone on my second trip a few weeks later after promptly quitting my life-draining day job in order to focus on this series.

Weeks later, I drove into the high Uinta Mountains from southern Wyoming aiming to complete the remaining three catches for Utah Cutthroat Slam.

As I passed by Flaming Gorge Reservoir above the Green River, I noticed I had a few bars of service and decided to pull over at a small, battered roadside interpretive sign.

Reading the sign, I noticed a small photo of a Colorado River cutthroat trout and a note about how they still lived in some of the headwater streams on that side of the mountain.

I decided this serendipitous moment was too much to pass up. There would be time to write later.

Stopping by a well-known fly shop in nearby Dutch John to confirm the sign’s information, a friendly young man at the counter proceeded to insistently tell me that there were no Colorado River cutthroat trout in Sheep Creek (the stream noted on the sign.)

“I went way back there a few weeks ago. Brookies one after another. If you want something easy to access and full of fish, check out this lake, though. They just stocked it,” the young man earnestly told me in an attempt to diffuse my obvious disappointment.

I still drove right to Sheep Creek. I was a day ahead of schedule and in the worst-case scenario it would be a nice place to camp.

Shortly after I arrived at camp, I suited up and tromped upstream. Almost immediately after stepping into the stream only mere meters from the closest occupied campground, I spooked a large fish.

“Well, either way, this could be fun,” I thought to myself.

No more than a few casts later, a very small but beautiful colored Colorado River cutthroat was in the net. The roadside premonition had proven true.

With time to burn, I continued upstream coming across a deep drop-off that entered a bend and had formed a deep pool.

I casted a dry-dropper rig into the run and let it slip over the ledge into the depths of the pool. I almost lost my footing in the slick stream when a large, darkly colored and intensely spotted fish lunged at the dry and attempted to pull me into the depths.

Everyone knows the moment I’m about to describe. Chaos ensued. My 1-weight rod, obviously overpowered, struggled to keep the strong fish from the main current. As soon as I brought it out of the current, I realized I had forgotten my net at the truck. When I finally got this fish below me, the reel fell off into the grass beneath my feet. As I grabbed the line with my hand, the fish, easily 17- to 18-inches and full bodied, made one last, exhausted run, and pulled the line taught and broke off the fly.

Thankfully, he, or another like him, was ready for seconds. It was as if I had been led to a unicorn of sorts by a small sign on the side of the road in downtown South Nowhere.

Continuing north, I entered the Cache National Forest after passing Bear Lake in pursuit of Bear River cutthroat trout on a tributary of the Logan River. The Bear River/Bear Lake cutthroat trout is an interesting subspecies with an even more interesting history. Even though the present-day Bear River terminates in the Great Salt Lake within the Bonneville Basin, these cutthroat trout actually evolved on a separate path from other Bonneville cutthroat trout.

At one time the Bear River was actually connected to Bear Lake and the Snake River drainage. The Bear River and Bear Lake cutthroat trout probably shared ancient ancestors with the cutthroat trout in the Snake River and Yellowstone drainages. After a long afternoon of spooking skittish Bear River’s in the plentiful beaver ponds along the upper section, I managed to bring a beautiful specimen to the net just as the sun disappeared beyond the far end of the valley.

I awoke on the Right Hand Fork of the Logan feeling as if it was in the bag. The only remaining species to complete my Utah Slam, the species that “counts” under my larger framework of Western Native Trout Challenge, was the Bonneville trout.

Thought to be extinct, pure strain Bonneville cutthroat populations were discovered in Utah in 1978. State and federal wildlife officials started working to bolster populations across the native range. In 1997, a group of grade school students petitioned the Utah State Legislature to change the state fish from the non-native rainbow trout to the native Bonneville cutthroat trout. Their enthusiasm and historical knowledge of the native fish convinced the politicians.

“Family and friends getting out and living this experience together is my favorite part. Hearing the stories of folks making memories that will last a lifetime. That’s what it’s all about.”

Brett Prettyman, Trout Unlimited

On the suggestion of a state biologist, I aimed to pursue the purest population of Bonnevilles I could in a tributary of the Ogden River. Paul Burnett, Utah Water and Habitat Program lead for TU, joined me on the river.

“This place pretty much shuts down when the sun gets high in the sky,” Burnett shared, as if I needed the extra pressure. “But, there’s a cutthroat in every one of these pockets.”

Why I was so concerned and what I hadn’t told Burnett, or Prettyman, or anyone else, was that this wasn’t my first time to this particular stream. After being forced out of the Raft Rivers weeks prior, I had unsuccessfully attempted to check off Bonnevilles at this same stream. The water had been off-color and obviously too high for its confined banks.

As we walked the heavily overgrown stream, we were nipped by small fish on our even smaller flies. Staving off admitted frustration Burnett and I talked about the role of native fish in his work.

“I hold native fish in high regard,” he explained. “I don’t think people really understand the threat native species are under. There are plenty of success stories surrounding Bonnevilles, sure, but, this stream contains healthy populations because it is largely county owned public lands that are mostly untouched.”

Suddenly and admittedly to my dismay, Burnett casually hooked his first fish, a small Bonneville while he explained what TU is doing along his main point-of-focus, the Weber River system. I was trying so hard and he literally kept talking while he hooked, reeled and released this beautiful native.

“We are focused largely on mid-elevation streams like this one,” he says. “Up high, cold water is relatively assured when we have plentiful snowfall. But in these mid-elevation streams, this is where fish should be able to migrate through and hold in the warmer temperatures and low water seasons.”

As is usually the case, while I was listening to Burnett explain how his team is actively monitoring and collecting data on more than 20 locations of the Weber, I felt a tug on the line and I was finally connected with my first Bonneville cutthroat trout. Letting it rest in the net, I examined its spotting and beautiful grayish body that seamlessly faded into subtle reds and oranges around the gill plates that made it perfectly camouflaged it with the streambed. Just like that, my Utah Cutthroat Slam was complete.

Not long after, as Burnett projected, the action slowed and we decided to take a short drive to check out one of his major projects.

Strawberry Creek, a tributary of the mainstem Weber River near Ogden, was one of the least likely fish conservation scenes I have ever visited.

Underneath the major highway, a large culvert/drainage corridor covered in colorful and ornate graffiti surrounded a massive metallic structure.

That metal structure, built in the fall of 2016, is a 385-foot long, 5 percent grade fish ladder responsible for 18-feet of elevation gain aimed to assist cutthroat from passing from the Weber to their spawning grounds in the tributaries.

“It naturally runs dry each year, usually not this early, but we’ve been able to track tagged cutthroat passing through the ladder during spawning runs,” Burnett shared with obvious pride.

The fish ladder was the first native cutthroat project funded through money generated by the Utah Cutthroat Slam. In the spring of 2017 native cutthroat were documented using the ladder and reaching headwaters for the first time in 60 years.

It was then that Prettyman and his 12-year-old son Owen joined us at the fish ladder site. Together, we set off for a nearby creek containing Bonnevilles in their native habitat where Owen was intending to finish his first Utah Cutthroat Slam. Turns out I wasn’t the only one having trouble finding the most “available” cutthroat of the bunch.

With the pressure of my own slam behind me, I focused on taking in the powerful scene of a father and son participating together in something obviously deeply important to both of them.

“Family and friends getting out and living this experience together is my favorite part,” the elder Prettyman told me. “Hearing the stories of folks making memories that will last a lifetime. That’s what it’s all about.”

True to his word, I watched the enormous smile erupt on Prettyman’s face when his son hooked into a Bonneville on a fly that he had picked and then tied on his own line.

“To be here when Owen completes his first slam,” Prettyman said, “is profoundly personally and professionally fulfilling.”

“It’s not all about the fish,” Owen Prettyman said to me in an interview after getting off the stream, saying that his favorite trip of his Slam was one on which he didn’t even get his desired fish. “It’s about who you are with. Instead of just catching fish, you have a goal and something to look forward to. Completing the slam is kind of a relief and it makes me want to start again.”

Many have started another slam. Brett Prettyman has completed this slam twice, and noted that there are several people who have completed the full circuit eight times over.

“A few people are trying to get their fish at a different stream every time,” Prettyman senior shared. “There are so many ways to do it. Yellowstone is restricted to maybe six streams, but other than that the possibilities are virtually endless.”

All of those entries add up. Thanks to that meager $20 entry fee, the Utah Cutthroat Challenge has been able to raise more than $62,000 to aid of each of Utah’s four native trout species. More than 3,300 people have signed up from all but four states.

It wasn’t until I was driving away, south into the Dixie National Forest on my way to Colorado, that I realized I myself had begun my own second Utah Cutthroat Slam. While casually fishing, after Owen had connected with his Bonneville, Prettyman and I of course had to wet our lines and I had caught a few myself.

As I headed south into the winding dirt roads of the aspen soaked Boulder Mountains, I said to myself, “I can’t believe I am still in Utah.”

But, now I did understand. I understood much more than I did before. I had made memories, with family (even if it’s not mine) that will last a lifetime and I suppose I’ll have to be back to finish out my second Slam.

You got me, Utah. You got me.