“Suddenly, there was an explosive rise not ten feet away, and an eight-inch trout came up out of the water to take one of the airborne mayflies. In all my life, it was the most memorable rise of a wild fish…” — Jimmy Carter

While I’ve never met President Jimmy Carter, he’s been a part of my life for a long time. I came of age politically in the early 1970s when the end game in the Vietnam War still stoked furious debate and the constitutional crisis of Watergate brought down the Nixon presidency. Historians, presidential scholars, and politicians fell over themselves to decry the excesses of what Arthur Schlesinger, Jr famously termed “the imperial presidency.” And young minds like mine were entranced with sorting it all out.

Part of the fallout from those shifting tectonic political plates was the 1976 presidential candidacy of Jimmy Carter, whose death this week, a few months beyond his 100th birthday, has sparked reassessment and tributes to the man whose one term in office as our 39th President often has been deemed a “failure.”

A little-known governor of Georgia, Carter campaigned as a breath of fresh air ushering in a new era after the twin debacles of war and scandal. “Why Not the Best?” asked the title of his political autobiography. A peanut farmer from Plains, Georgia, his biggest claim to fame prior to his presidential run may well have been being Georgia Governor in 1974 when Henry Aaron hit his 715th home run for the Atlanta Braves.

As a young journalism major and editor of my college newspaper, I covered Carter’s campaign speech at Moravian College in Bethlehem in the lead-up to the 1976 Pennsylvania Democratic party primary. He won that primary and went on to defeat incumbent President Gerald Ford, who assumed office upon Nixon’s resignation. Years later I would be the second scholar to visit the newly opened Carter Presidential Library in Atlanta to do research on a book about the presidencies of Carter and his successor, Ronald Reagan.

An open-minded president

In today’s climate of political polarization and rampant cynicism, it may sound hopelessly nostalgic to think that a Presidential candidate could campaign on a platform emphasizing the positive aspects of political life. Today a candidate Carter—America’s first born-again Christian President—might be eviscerated by his political opponents as nothing short of a “radical leftist.” In his day, Carter was criticized for, among other things, expending his early political capital on the Panama Canal Treaty, his handling of a struggling economy, the widening energy crisis, and of course, the seizure of U.S. hostages in Iran as a result of the Iranian revolution. Indeed, Carter was scorned (and challenged in the 1980 Democratic primary) by the likes of Massachusetts Senator Ted Kennedy, the liberal lion who distrusted someone with so little experience in the hardball world of Washington politics. Carter, the moderate Democrat, took it from all sides.

Carter was open-minded, not a doctrinaire. His penchant for picking policy advisors with contrasting liberal and conservative viewpoints—think Cyrus Vance as Secretary of State and Zbigniew Brzezinski as National Security Advisor—paved the way for Reaganism in his final two years in office, as he instinctively moved to the right on economic and national security policy. He was capable of rethinking his earlier positions, even on one of his most significant accomplishments, the 1978 Camp David Accords, signed between Egypt and Israel. The Accords were specific on Israeli withdrawal from the Sinai Peninsula, but vague on how to achieve recognition of the “legitimate rights of the Palestinian people.” Decades later he would revisit the Middle East conflict, writing Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid, a book that won him acclaim but also incurred the wrath of many supporters of Israel, including fellow Democrats and board members of his own foundation.

Much more than just a President

Carter, of course, lost his reelection bid in 1980. Yet America’s longest-lived President reasonably can be thought to be the nation’s greatest, most exemplary “ex-President.” Author of more than 30 books on a wide range of topics, Carter returned to Plains and embraced his post-presidency as an engaged citizen, mostly shunning the pomp, power and lucrative corporate speaking engagements that await contemporary former chief executives.

Along with his wife Rosalynn, he devoted himself to decades of humanitarian work, much of it under the auspices of the Carter Center they co-founded in Atlanta. Long an advocate of and volunteer for Habitat for Humanity, Carter immersed himself in worldwide humanitarian causes, including advocacy for women’s rights and serving as an international election monitor in troubled regions around the world. Among the many accolades he received after leaving the White House, his ceaseless efforts to find peaceful solutions to international conflicts earned him the Nobel Peace Prize in 2002.

Presidential angling

Beyond the tumult of political controversy, he took time to regain his bearings and immersed himself in the quiet of nature, most notably with a fly rod in his hand. He invited many luminaries in the world of fly fishing to Camp David in for what he called his “fly fishing summit” where, as a willing student he initially learned how to fly cast and tie flies. He enjoyed fishing Hunting Creek just down the road from the presidential retreat in Maryland. He became famous for his recreational stealth, landing at Camp David, slipping the Press, and taking off again in a helicopter to land 40 minutes away in the field of his friend Wayne Harpster along Spruce Creek in Pennsylvania. Of his clandestine trips to fish with Harpster, he wrote: “These jaunts were among our best-kept secrets in Washington.” In fact, he made sure to fish the green drake hatch on Spruce Creek with Harpster for some forty years thereafter.

His 1988 book An Outdoor Journal: Adventures and Reflections chronicles his life as an avid outdoorsman. In his typically factual, unadorned prose he tells stories of learning to hunt and fish in rural Georgia, and later grouse hunting in northern Michigan, turkey hunting in his home state, fishing with wet flies and streamers in Wales, and hiking in Nepal.

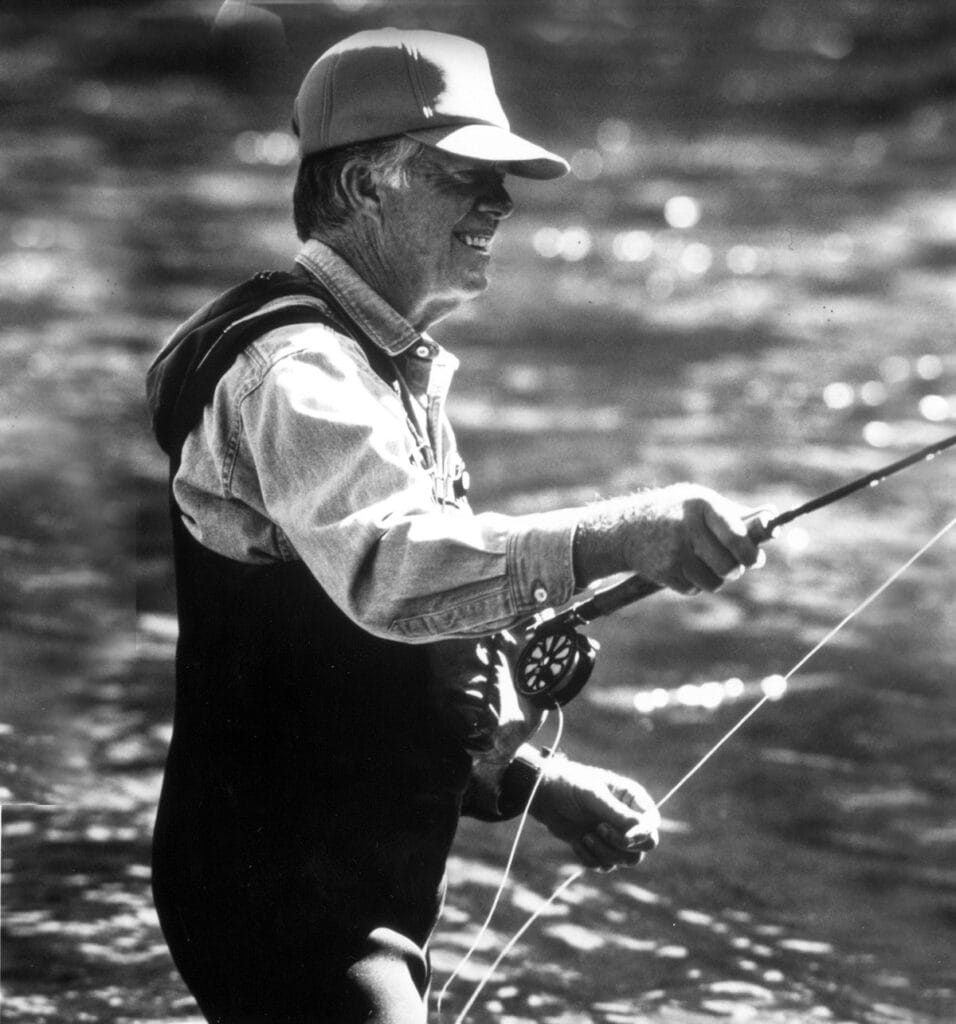

But I find his reflections on fly fishing especially poignant. He recounts stories of angling around the Yellowstone area, notably fishing for grayling on Grebe Lake in the Park and Poindexter Slough near Dillon. He fished the Madison River and Hebgen Lake outside of West Yellowstone, the Snake River in the Tetons, and the Henry’s Fork in Idaho. And to capture it all, the cover of the book shows a smiling post-president Carter fly fishing on the Boulder River near Big Timber [see picture below].

These venerable waters take a back seat, though, to the fly fishing he did in the north Georgia mountains. Upon leaving the presidency in 1981, the Carters were looking for land on which to build a small cabin to escape the frenzy of their official lives. They settled on a spot in the woodlands along a small stream called Turniptown Creek. The now-former President consulted Georgia Fish and Wildlife biologists about the fishing prospects, and he was told that the creek could not support a wild fish population, but officials would have it stocked if he wanted.

Disappointed but not deterred, months later Carter found himself sitting on a rock at the base of the creek’s modest pool, watching mayflies emerge and flutter on the surface. In a sudden, unexpected flash a small wild rainbow rose to devour a fly: “In all my life, it was the most memorable rise of a wild fish, exceeding in my mind even the soaring leap of a mighty blue marlin off the coast of Aneġada Island in the eastern Caribbean.” To glorify what many would consider at best a modest occurrence—that little trout would not be gracing the hallowed “wall of fame” in Livingston’s iconic Dan Bailey’s Fly Shop—takes a keen a sense of proportion, an appreciation for the wonder and awe of simple acts of nature.

As a cultural bonus, Carter would be in tune with the Livingston music scene as well. A longtime friend of Willie Nelson’s, he once remarked that “Greg Allman and the Allman Brothers just about put me in the White House” with fundraising concerts during his presidential campaign. It doesn’t take a great leap of imagination to see him whooping it up while Jimmy Buffett sang “Livingston Saturday Night” at the former Wrangler Bar for the 1975 film Rancho Deluxe.

In short, may I suggest Jimmy Carter be remembered as a Livingstonian at heart. Fishing into his 90s, he was kind, unpretentious and an authentically decent human being who embraced the small-town community spirit of tolerance and civic participation. Moreover, the man could lose himself in the pursuit of an eight-inch trout on a supposedly fishless creek.

I know when I find myself knee deep on the Shields, the Boulder, the Yellowstone or various waters within the Park, you can be sure he’ll be out there casting alongside me.

William Grover teaches at Montana State University, Bozeman. He is Emeritus Professor of Political Science at Saint Michael’s College in Vermont. His books include The President as Prisoner: A Structural Critique of the Carter and Reagan Years (1989) and The Unsustainable Presidency: Clinton, Bush, Obama and Beyond (2014, with Joseph G. Peschek). His fly fishing stories have been published in the Big Sky Journal, The American Fly Fisher, the Livingston Enterprise, and the Yale Anglers’ Journal. He lives in Livingston.