Catching westslope cutthroat trout and seeing the forest through the trees in north-central Idaho

Editor’s note: Daniel Ritz is fishing across the Western United States this summer in an attempt to accomplish the Master Caster class of the Western Native Trout Challenge. He will attempt to land each of the 20 native trout species in their historical ranges of the 12 states in the West. You can follow Ritz as he travels across the West by following Trout Unlimited, Orvis, Western Native Trout Challenge and Montana Fly Company on social media using the #WesternTroutChallenge.

In another chapter of life, I rode a motorcycle. As a struggling writer, I endured what I now affectionately refer to as my “personal recession,” by selling my perfectly good Chevy pickup for a 2011 Steve McQueen model Triumph Scrambler.

Each year, my best friend Mark and I would take a road trip on our bikes over the Fourth of July weekend. In 2019, we rode across Idaho through Jackson, Wyo., north through Grand Teton and Yellowstone national parks before enduring a hellacious 400-mile day to get home in the howling winds of central Idaho.

I’ll never forget riding through the fields of eastern Idaho with golden, ocean-sized mosaics of grain flowing in the wind just enough to make me wonder if my vision was going blurry and if maybe it was time to lay off the throttle.

Mark’s bike was unfortunately in the shop for some untimely repairs the next summer, so we decided to take my truck for our yearly tour. We had planned to leave Boise and head off in a counterclockwise circle, taking a few days and visiting some of his family in Colton, Washington, before crossing northern Idaho into Missoula, Mont. From there, we would travel down and through the famed Lolo Pass on US Highway 12, one of the most famed motorcycle road trips in the United States.

Then, as some may remember, a major rockslide occurred on US Route 95, closing all routes southbound to Boise. We were stranded in Missoula and made the difficult decision to forgo US Highway 12 and adjust our course and head south along the Salmon River before heading west.

“It will be better on the bikes anyway,” I remember Mark saying. “We’ll do it next year.”

One week before I was scheduled to fish for westslope cutthroat trout as part of the Western Native Trout Challenge, I visited Wisconsin to join a group of men from the Midwest to celebrate the end of Mark’s bachelorhood. While I had been out working to complete the challenge Mark and his to-be wife had already decided to up and move back to the suburbs of Chicago. As I documented (with a certain amount of discretion) the bachelor party and then the wedding, I silently suffered the loss of a dear friend who was understandably too busy soaking in his new life to recognize my turmoil.

I thought of Mark as I crossed Washington after my pursuit for coastal cutthroat. It was a temporary distraction, knowing all the while I was staring down the barrel of yet another disappointment.

In the days since returning from Mark’s wedding in Chicago and almost immediately departing for the Olympic Peninsula, a major fire complex had begun to burn along the St. Joe River in northern Idaho. I had been excited to fish the St. Joe for years. Shortly after I finalized my plans for this series with Trout Unlimited, one of my favorite fly-fishing authors and Trout Unlimited digital content editor, Chris Hunt wrote an inspiring piece on the St. Joe and its illustrious cutthroat that made me even more eager to go.

I was being refused, again. Not to mention, time was drawing short and my funds even shorter. The combination forced me from taking any of my planned out-of-the-way trips such as Kelly Creek, the North Fork of the Clearwater and others to remain unnamed.

When I reached Lewiston, Idaho, I was forced to make my decision. With my dreams of the northern route and the St. Joe shattered, and knowing I had an eventual destination of Missoula, I scoured my gazateer for a more direct route.

I called my own fiancé, needing to vent my frustrations in what I described as “settling.”

“This was supposed to be the best part of the trip,” I pouted, whimpering like a tall, sunburned, camo-clad toddler not getting his way. “I didn’t want this to be the species I just ‘go catch fish’ and be done with it.”

Minutes later, I called her back.

“I’m going to fish the Lochsa,” I said. “I’m sorry, and frankly, I’m embarrassed. I need to check myself. I’m going to spend the long weekend (it was Thursday) slowly making my way up the Lochsa, along U.S. Highway 12. You’ll hear from me by Monday at the latest.”

I had decided to fish the Lochsa and I was going to drive up U.S. Highway 12 to Lolo Pass in honor of my friend, recently swallowed by the suburban dream. We never got to do it together, and I sold my motorcycle to partially fund this trip, but damn it, I was going to do it for us both.

It felt therapeutic.

After midnight, I arrived at Knife’s Edge Campground, on the lower Lochsa. I could hear fish popping and thought I could make out ripples in the almost full moon. I thought of my friend and the nights when we stayed up too late drinking whiskey that we only slightly regretted.

The next morning, rain drizzled steadily, and the fog took it’s time drifting up and over the ceiling of the surrounding canyon.

It wasn’t long before I got my first cutthroat trout. I quickly realized while the Lochsa is a sizable river, maybe 40 or 50 yards wide at the widest parts of the lower and middle sections, the fish were densely congregated along the edges of the river in the seams between the quicker moving currents in the middle of the river and shallows of the rocky banks.

With time on my side, I enjoyed the fog and rain as I climbed the boulder-ridden bank of the river up, and back and up again. I consistently connected with eager 10- to 14-inch westslopes.

I camped that first night within spitting distance of the river. The silence was encapsulating, and fir, pine and spruce trees loomed overhead, shadowed by the glowing moon only enough to outline their intimidating height.

The Lochsa River plunges some 60-plus miles from Lolo, Mont., towards its confluence with the Selway River in Idaho where it combines to form the Middle Fork of the Clearwater. Originally described by European Americans by none other than the Lewis and Clark Corps of Discovery in 1805, the river rises more than 6,000 feet from its mouth to its headwaters within the Bitterroot Mountains. Importantly, the Nez Perce Tribe had lived and likely fished along the Lochsa for eons before the party of white “explorerss” were guided over the spine of the Rockies.

“The Lochsa’ wildness endures almost two centuries later,” authors Rocky Barber and Ken Retallic state in their book Flyfishers Guide to Idaho. “Chinook salmon and steelhead have not fared well, but fat, sassy westslope cutthroat abound in today’s fishing places.”

As I worked upriver, past the Wilderness Gateway where most anglers believe the true fishing begins, I began to find myself focusing more on premier holding spots, hoping to get the fish I was seeking. I wanted to catch a trophy. I felt as if I needed something exemplary to make this a memorable trip.

I began getting frustrated with the countless 10- to 12-inch fish that launched themselves at my flies, sometimes only seconds after landing on the water.

I began scaling up my flies to ludicrous-sized terrestrials to tempt larger fish. You would be impressed by the size chubby Chernobyls a run-of-the-mill westslope will hit.

At some point, now soaking in the blazing August sun directly overhead, I became disgusted with myself as I realized I was disappointed by catching what I was internally categorizing as “mediocre” fish. I was so focused on getting “the one,” and making up for all the loss and frustration I was feeling that I had totally lost perspective.

These thoughts continued to rattle through my mind as I came upon a sign on the southern side of the river notifying me that I was exiting the Wild and Scenic portion of the river.

I decided to turn back. I decided to do one more day, to enjoy my time and soak in the experience and hopefully exit my ascent of the Lochsa with some sense of closure on the loss of a friend and my still having not reached the north central Idaho mecca’s I had anticipated.

The next morning, in an effort to shake off my childish attitude from the day before, I tried a different tactic, I crossed a wide but shallow section of the river just before a bend. I was going to fish up one of the smaller tributaries that disappeared into the surrounding wilderness.

However, as I crossed, I saw a series of horseshoe shaped rock structures in the middle of the river, well below the emerald green surface. These rock structures were forming what looked like small islands of oil-slick darker green water.

I casted a smallish gray X-caddis pattern slightly upstream of the pockets, attempting to keep my line off the water to allow the fly to drift through inconspicuously.

From the depths of the second horseshoe, a large silver torpedo emerged and slowly rolled up towards the service, displaying its full girth. The largest westslope I had ever seen slowly and fearlessly gulped my fly with the confidence only apex trout have.

As I brought the fish to the net, I was overwhelmed with its weight, length and textbook coloring.

As I resuscitated this fish in the slow but moving waters along the side of the Lochsa, I thought of Mark, and I wished that he could have seen this.

Summiting Lolo Pass, I stopped along the side of the road, taking in the wilderness below me, now to the east and south, and thought about all that I was leaving behind.

I thought of a conversation I had with Martin Koenig, Sportfishing Program coordinator at Idaho Fish and Game months before.

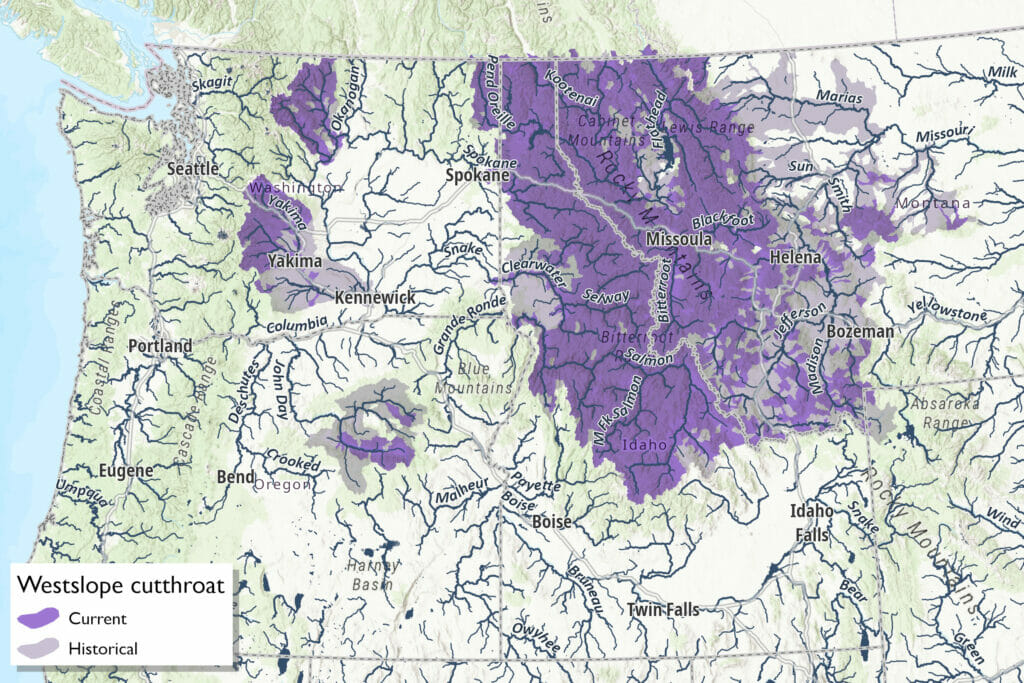

“Westslope might be in the best shape of any of the natives,” he had said. “The majority of their native range, which was the largest of all of the native trout of the West, is largely still intact and doesn’t really coincide with development.”

As I reflected on Koenig’s comments, I began to realize the error of my ways.

I was so disappointed with the loss of my friend, at least in the bachelor kind of way, and the inability to fish at these highlight-reel, bucket-list locations, that I had focused on the losses of singular exemplary moments as opposed to recognizing the beauty of the abundance.

Staring out into the checkerboard landscape beneath me, I smiled to no-one as I thought of how I had just enjoyed three days of world-class fishing for a native species on one of the least disturbed and iconic rivers in America — as my third or fourth option.

It has been said that westslope cutthroat trout can be difficult to identify as compared to their more distinctly colored cousins like the Yellowstone or Colorado River cutthroat trout. Maybe westslopes aren’t as easy to identify because we often don’t choose to focus on what is bountiful and readily available.

I had been so focused on not being able to ride Lolo Pass on a motorcycle, I no longer owned with my best friend that moved more than 2,000 miles away, that I had forgotten all the miles we had literally and figuratively logged together.

As wonderful as that single trophy fish was, and believe me, I plan on framing a photograph of it on the wall in my office one day, the true beauty is that westslope cutthroat trout are still abundantly available.

That isn’t always the case, with dear friends, motorcycles and especially with native trout, and as the rumble of a trio of leather clad, middle-aged bikers climbed towards me, I finally saw the forest through the trees.

They may not always be there, and if they aren’t, the westslope may not be either.

This essay is dedicated to a dear friend. Mark. May your life always be as dense as you desire.