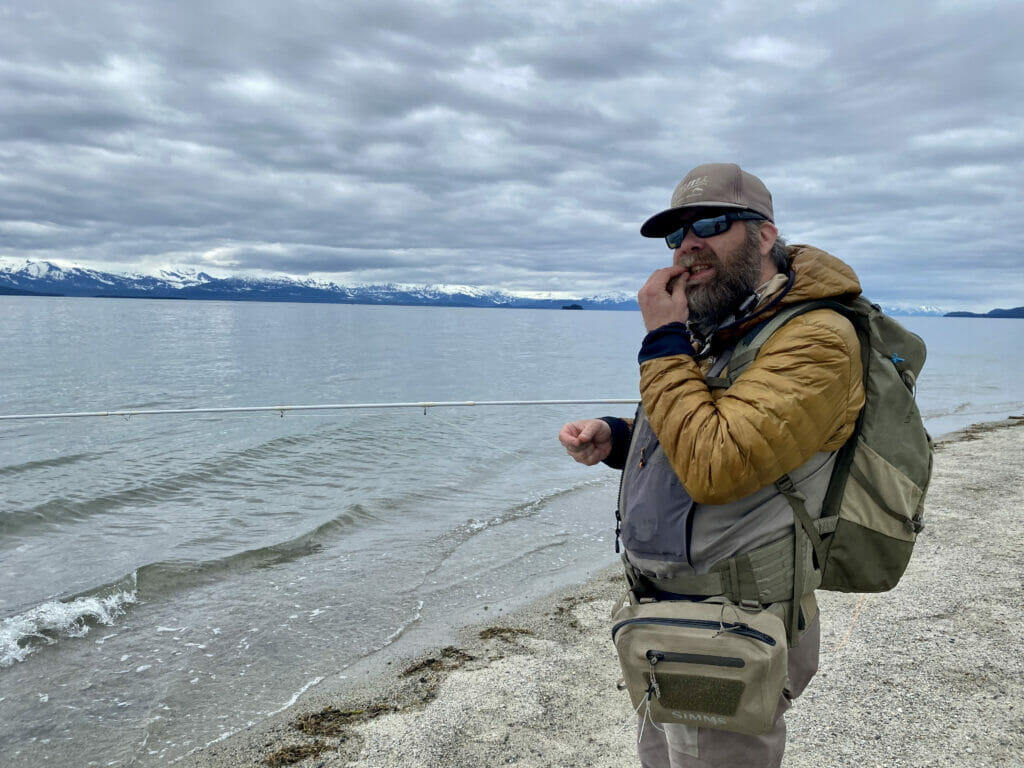

The author traveled to the end of the road in his pursuit of Dolly Varden. Daniel A. Ritz photo.

Searching for Dolly Varden in southeast Alaska

Daniel Ritz is fishing across the Western United States this summer in an attempt to reach the Master Caster class of the Western Native Trout Challenge, attempting to land each of the 20 native trout species in their historical ranges of the 12 states in the West. You can follow Ritz as he travels across the West by following Trout Unlimited, Orvis, Western Native Trout Challenge and Montana Fly Company on social media using #WesternTroutChallenge.

We embarked for Alaska the day before my 34th birthday, only days after leaving my corporate editing job and hours away from asking my partner for her hand in marriage. For these reasons, not to mention the pursuit of the challenging species that lay ahead, I was unprecedentedly nervous and equally excited.

I headed to Juneau, in southeast Alaska to meet Mark Hieronymus and pursue coastal cutthroat trout and Dolly Varden, the first two of six total native trout and char species of Alaska I was targeting for the Western Native Trout Challenge.

Hieronymus is well known in commercial and recreational circles having owned a seafood processing company before becoming a fulltime fly-fishing guide for Bear Creek Outfitters in Juneau.

It wasn’t Hieronymus’ MVP resume that interested me in partnering with him in pursuit of coastal cutthroat and Dolly Varden, both of which have anadromous life histories. In Trout Unlimited’s recent film ‘Anadromous Waters’, Hieronymus, who works as the community science coordinator for Trout Unlimited Alaska, shared how he has been leading the charge in expanding the state’s Anadromous Waters Catalog in order to recognize and protect valuable habitat for the salmon and steelhead, largely on Alaska’s Tongass National Forest. It was fascinating to me.

According to Alaska Department of Fish and Game, the catalog “currently lists almost 20,000 streams, rivers or lakes around the state which have been specified as being important for the spawning, rearing or migration of anadromous fish. However, based upon thorough surveys of a few drainages, it is believed that this number represents a fraction of the streams, rivers and lakes actually used by anadromous species. Until these habitats are inventoried, they will not be protected under state of Alaska law.”

When we first spoke via a video call in early March, our initial plan was to take a small plane to a not-yet-inventoried stream in order to document the existence of Dolly Varden and coastal cutthroat trout. This, we theorized, would meet the needs of my Western Native Trout Challenge series project as well as showcase the AWC nomination process.

After arriving in Juneau I was deflated as Hieronymus informed me a dismal weather forecast and a broken water gauge made him skeptical of our success if we ventured off into the wilds.

There went my chance to make Alaska fishing history. It didn’t seem fair.

Hieronymus asked where I was staying. I told him I was staying at a bed and breakfast just north of downtown Juneau.

“Ha!” he laughed, as I continued to try to mask my now spiraling disappointment. “Tell you what, there’s a fantastic cutthroat creek not far from your place and I know of a Dolly beach that can be nuclear on the outgoing tide if you want to do that. We can still try to fly out, but it could be really expensive and I can’t guarantee success. Want to just stick around town?”

Staring down a four-month project on a fixed income, that was a risk I couldn’t take.

The next morning, on my birthday, Hieronymus met me at the bed and breakfast and we ventured, as he mentioned, no more than 500 yards to a small creek outlet where he hoped to “knock out a few cutthroat before we head to the beach.”

“How was your flight?,” he asked.

“Shockingly smooth,” I said honestly. “Hard to believe you can get to the ‘Last Frontier’ before breakfast.”

After an unsuccessful hour or so trying to get cutthroat at the confluence of the inlet creek — he had mentioned that coastal cutthroat trout are famously more active in the early and late low-light hours — Hieronymus assured me we should head out to make sure we hit the tide.

“Should be good. We have a big tide today. A 3-foot low to a 16- or 17-foot-high tide today,” he said. “The tide pushes those salmon fry and smolt out of the river and off the beach and the Dollies just cruise the pockets and feast.”

As a lifelong waterman — I was pretty heavy in the surfing scene for a while — this was a tidal event first for me.

“Mark, it seems Dolly Varden get a lot of bad press. That they eat all the precious salmon eggs, they out populate and take food from more favorable sportfish. Is that true?” I asked as we walked the path from the road to the beach.

“I call Dolly Varden ‘the people’s fish,’” he said, smirking. “They have a wide range, are super adaptive, have multiple life forms and never get any credit.”

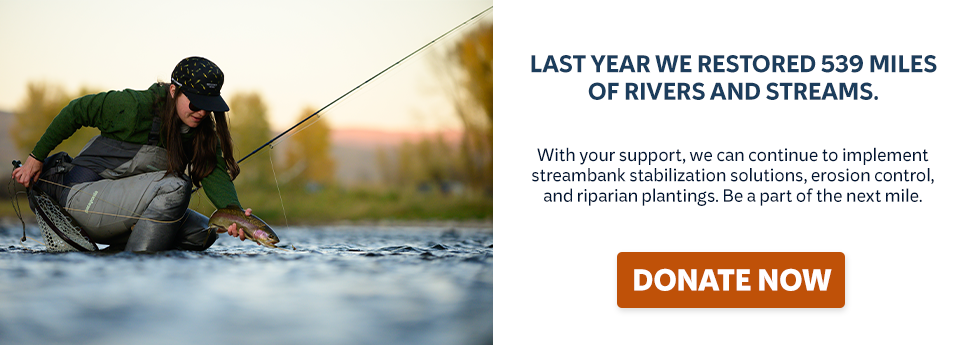

After a multi-mile hike through dense hemlock and spruce along a glacial river, we arrived at a sandy beach where we were delighted to see Dolly Varden exploding from the surface of the water.

‘Charrrrrrrrrrrrrrr!” Hieronymus exclaimed in his best pirate imitation. Fully bearded and shielded head-to-toe from the occasional rain and constant wind, I never saw him any other way.

For hours we walked the beach, casting and stripping fry imitations of Hieronymus’ own design into the surf. We pulled in one 15- to 18-inch chrome sided Dolly Varden after another.

“People love to talk about how Dolly don’t fight,” Hieronymus yelled from down the beach, rod bent and pulsing. “Sure, they’re not a steelhead, but they’ve got no quit. The people’s fish!”

Walking back toward the beach I asked him what he sees as the major issues specific to trout in southeast Alaska.

“The way of the salmon is the same as the trout in Alaska, and I think the most important thing is that people begin to recognize that all of this is habitat. All of it. Not just that river (pointing to the main river leading to the salt water we just finished fishing) but also the tributary up there (pointing toward mountains) and that over there (pointing to the small path side string of water running alongside our trail).”

When Hieronymus says that habitat isn’t just the superhighways, I ask what he means.

“When we think about people, and the ‘habitat’ people utilize, we don’t just look at the superhighways where they can easily be seen traveling,” he said. “People don’t live on the freeways, people don’t ‘spawn’ on the freeways or on their commute.”

The next day, we continued a bit further toward the “End of the Road,” and got into fewer, but larger, Dolly Varden on another beautiful creek that runs into the sea. One deep bend after another, I found myself distracted by what Hieronymus had said the day before. Instead of the prime lies and pristine logjam pools and deep bends, I found myself paying a bit more attention to the small side-tributaries or the stream side meadow that reinforced the almost vertical banks of some of the pools.

I found myself thinking about what might affect where the trout live, wondering where they spawn, where they travel and feed. Where does their food find food? I wondered what the world would look like and what sort of misguided decisions we’d make as a society if we just observed our own human culture from the nightly news traffic helicopter.

Our initial highlight reel plan of flying out and documenting never before recognized streams is something I hope one day to have the ability, know-how and means to do, but while there is great value in Hieronymus’ pursuit of recording history in order to preserve it, I was happy that my journey led me down another path.

True discovery, for me, and understanding of a bit more of the blue collar char, “the people’s fish” was right down the road. It was right under my nose the whole time.

Returning from our pursuit of Dolly Varden late in the afternoon, I rejoined my soon to be financé, thanking her upon my arrival for finding such a wonderful place to stay. She had no idea that the next day, deep in a remote forest in southeastern Alaska, she would agree to be my partner forever.

Before I did that, under the still-waning midnight sun Alaska offers in June, I geared up and took a little walk after she had fallen asleep. Emerging from the brush at nearly 11 p.m., onto the small island where Hieronymus had assured me fish would be waiting for the fry to be pushed out of the creek, I proceeded to catch coast cutthroat trout, 11 casts in a row.

As much as the unknown was “out there,” everything I needed to understand was right there the whole time.

It took traveling 2,150 miles for me to realize protecting the future of our native trout likely begins with looking under our own feet. The same thing can be said about my future wife.