Invasives and overconfidence cloud early efforts to bring an Apache trout to hand

Daniel Ritz is fishing across the Western United States this summer in an attempt to reach the Master Caster class of the Western Native Trout Challenge, attempting to land each of the 20 native trout species in their historical ranges of the 12 states in the West. You can follow Ritz as he travels across the West by following Trout Unlimited, Orvis, Western Native Trout Challenge and Montana Fly Company on social media using the #WesternTroutChallenge.

After coming from the Mogollon Rim and Gila country of New Mexico, I must admit, heading into the White Mountains of Arizona, away from the fuel town of Alpine, felt somewhat tame.

In addition to what Zach Beard, native trout and chub coordinator for Arizona Department of Game and Fish, called the “non-soon,” Apache trout, much like Gila, are at high-risk for hybridization and habitat competition with invasive species like brook trout. Originally listed as an endangered species under the Endangered Species Act in 1967, Apache trout were downgraded to “threatened” in 1975.

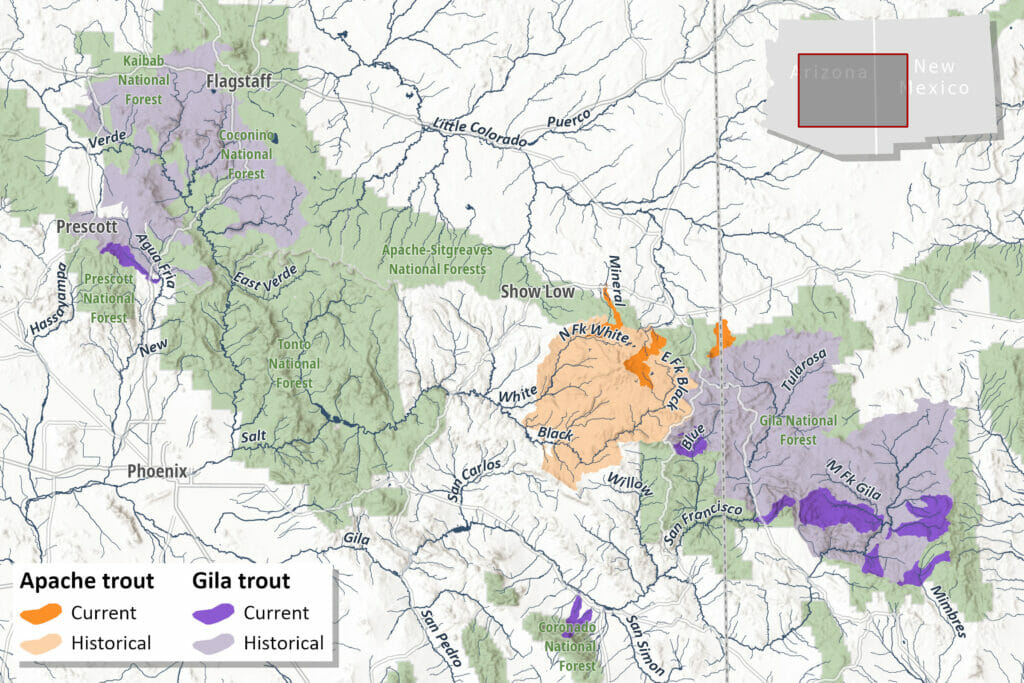

Historically, Apache trout only naturally existed in three waterways in the entire world: the White River, the Black River and the Little Colorado river systems of Arizona.

While all original, “relic” lineages exist only on Fort Apache reservation of the White Mountain Apache Tribe, Beard shared that Apache trout have recently achieved a milestone population mark. In the 1975 recovery plan accompanying delisting from endangered status, 30 sustaining populations were named as the goal signifying sustainable, healthy progress. Beard shared that as of recently, there were exactly 30 successful populations of Apache.

After the successful, but trying experience of the Gila trout in the burned landscape of New Mexico, I was excited for a less-stressful native trout experience in Arizona. Like the Gila, the Apache trout serves as the “canary in the coal mine” when referencing the watersheds here in the arid Southwest.

Arriving at the West Fork of the Black River, I was relieved to see a small, flat, meandering stream bending through ranch land up into the forests of the headwaters.

Maybe the hard work was behind me?

In the heat of the Arizona afternoon, I decided to rig-up and give the stream a go straight-away. Maybe I could make quick work of the Apache? After tying on a hi-vis parachute Adams variation, I crossed the half-mile or so from camp to the nearest bend with a deep pool.

Not seconds after my fly hit the bank, a take!

A small fish launches itself from the bend, inhaling my fly. Eager but small in stature, I quickly brought it to hand, anxious to observe my success in the flesh.

This fish was a first, but not like I had anticipated.

In my net, a 4-6 inch vibrantly colored brook trout.

Beard and AZDGF had thought they had cleared the West Fork of the Black River of brook trout in the 1990s, but in the early 2000s discovered brook trout in the stream. Since then, a series of three fish barriers, the latest built as late as 2015, were meant to keep brook trout divided from the native Apache. The key phrase being “meant to,” of course.

For the next 45 or-so minutes, I proceed to catch maybe a half-dozen small brook trout in rapid succession. Each time I saw a small fish rise from its hiding spot to take my fly, my heart skipped a beat, wondering if it was the native Apache.

Finally, after meandering the slow bends and pools of the West Fork, I connected with my first Apache. Awash in relief, I looked forward to days of hooking a healthy mix for fish.

Unfortunately, that was the last Apache, in fact, the last fish, I would see on the West Fork of the Black River.

The next morning, I woke up shivering in my tent. Snow? There was a thin layer of crust on the ground and snow on the top of my tent. Maybe the White Mountains had a few curveballs up their sleeve after all?

Now, more than 2-½ miles into the headwaters, I was yet to see another fish, let alone a native Apache. I made my way back, pool by pool, wondering if my confidence had gotten the karmic better of me.

Someone wiser than me once advised me, “don’t leave good for better” so peeling away from the West Fork was a difficult decision.

Pulling up to the West Fork of the Little Colorado, you see a prominent sign for the Baldy Wilderness, the smallest wilderness space in the United States. The sign features a quote from Edward Abbey, author of, amongs others, the fierce defense of wilderness and anti-development Desert Solitaire.

“Wilderness is not a luxury but a necessity of the human spirit,” the sign quoted.

Here’s a map of Daniel Ritz’s summer travel plans, where he hopes to catch the 20 native trout and char species and earn his master class designation under the Western Native Trout Challenge.

I spoke with a gentleman fishing the pool next to the trailhead.

“Get anything?,” I asked.

He had not, he reported. He hadn’t even seen a fish.

“It’s a good day to be out here, though,” he said. “I think there’s some big ones up that way in those beaver ponds. A real bitch to get to, though.”

In my opinion, beaver ponds are also a necessity to my human spirit.

In a large back eddy, a pod of sizable trout were sticking close to the bottom. I decided to swing a wet fly, a variation of an orange hot-spot hare’s ear nymph. Some flies have a certain mojo, and this was a variation (a fancy way of saying sloppy and homemade) of a favorite of my personal fly-fishing hero, John Wolter of Anglers Fly Shop in Boise, Idaho. As the sun began to set behind the pines to the south and west, it was time to pull out my “Hail Mary” fly.

Waiting for a tug, the swings seemed to take hours as I ran back and forth upstream to my lookout point to check my positioning.

Finally, the line went taught and I saw a yellow flash on the surface. An Apache trout, easily twice the length and girth of the specimen from the Black, thrashed violently in the otherwise glassy beaver pool.

On bended knee, I brought the fish to eye level. Apache trout have a unique feature in their eyes, an easy giveaway of a genetically pure Apache. They appear to have a black stripe or mask through each of their eyes, due to two small black dots on either side of the pupil. Truly one-of-a-kind.

On my knees on Little Colorado, I thought of something AZDGF statewide Native Aquatic Program Supervisor Julie Meka Carter had told me.

“I think the story of the Apache, the story of the Southwest, is that this is the only place — these three small streams — the only place in the entire world where these fish exist. This is a rare and unique experience,” Carter said.

I thought of how, when speaking of previous trips through Escalante and Gila country, I had remarked at the unique beauty of these environments, going so far as to describe them as alien. They may seem alien, but maybe they are simply unfamiliar.

“I think the story of the Apache, the story of the Southwest, is that this is the only place — these three small streams — the only place in the entire world where these fish exist. This is a rare and unique experience.”

Julie Meka Carter, Arizona Department of Game and Fish

The Southwest and it’s Mogollon rim aren’t alien in the sense of “from another planet.” They, like the trout that inhabit them, are one-of-a-kind places on this very same planet.

It was me that was out-of-touch. But a little less so now.

As the wind continued to scream through the barren, burnt landscape of the White Mountains, I wondered if it sounded anything like the warning offered by the canary.