Roger Phillips photo.

By Roger Phillips

They’re big, they’re hard-fighting, and they’re one of Idaho’s most overlooked trophy fishing opportunities, but many anglers are still confused about whether they can target bull trout for catch-and-release fishing.

The short answer is yes.

When bull trout were listed as threatened under the federal Endangered Species Act in 1998, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service determined state fishing regulations provided sufficient conservation benefits. In Idaho, that meant bull trout fishing was allowed, but harvest was not.

Those regulations are still in place, so bull trout can be caught, but they must be immediately released unharmed. While they’re not as abundant as other types of trout, Idaho’s bull trout populations are generally in good shape and capable of supporting some great catch-and-release fishing opportunities.

Though you can’t take them home, fishing for bull trout can be exciting because they’re large fish and aggressive by nature, and they can be caught on flies, lures and bait, if the body of water is open to bait fishing.

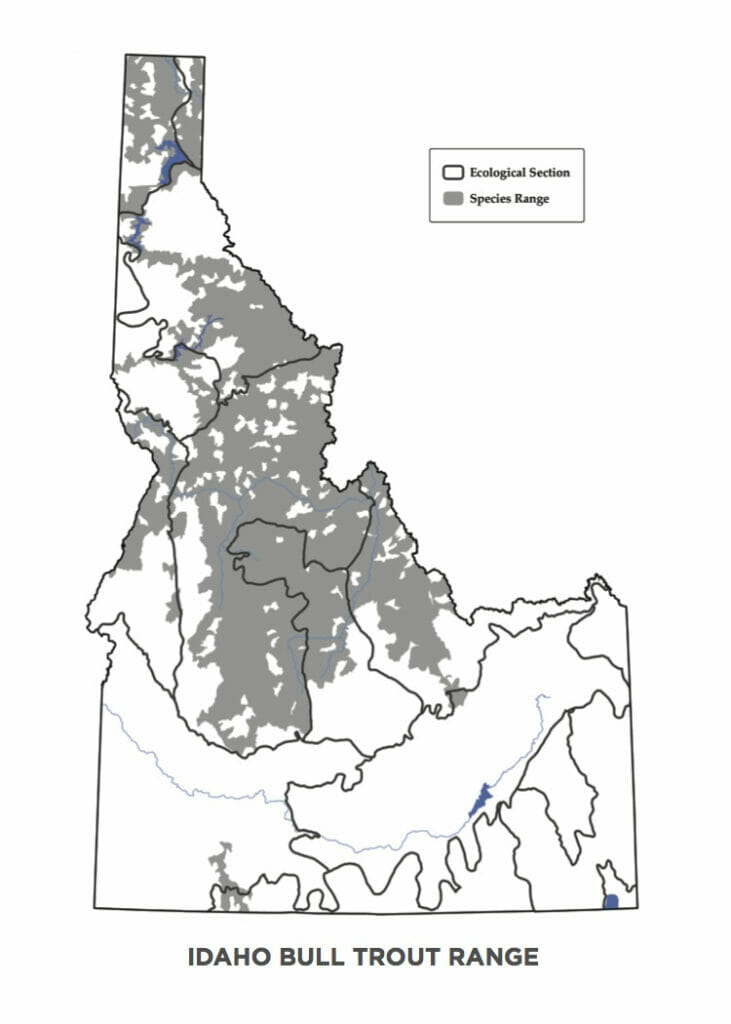

Bull trout are widespread in Idaho, mostly in rivers and streams, but they can also be found in lakes and reservoirs. They are in most river drainages in central and northern Idaho that flow into the Snake and Columbia rivers. They’re most common in coldwater rivers, which in summer often means upper-elevation streams. Bull trout need water that’s 60 degrees or cooler, and water that’s around 54 degrees is ideal habitat for them.

Many bull trout will seasonally migrate through watersheds. Some will winter in a large river, or lake or reservoir, then move into tributaries and headwaters during summer. They spawn in early fall and then slowly migrate downstream to complete the cycle. In some systems, this round trip can be 50 miles or more.

Because of their migratory nature, bull trout can be a challenge to locate, but if you know their seasonal patterns, especially as they move into the high country during summer, they can congregate in relatively small streams.

When young, bull trout eat insects, but as they grow larger, they shift their diet to other fish. Bull trout evolved with whitefish, sculpins and other trout, and consume them as food.

How large a bull trout grows depends on where they live and how much food is available, but even in relatively small streams, they can dwarf other resident trout species. The state-record bull trout is 32 pounds, which was caught in 1949 from Lake Pend Oreille when harvest was legal. The current state record for catch-and-release is 23.5 inches from the Salmon River.

The bull trout’s relatively large size and the water clarity where they often reside means anglers can spot them in holding water. But they’re remarkably well camouflaged and become almost invisible, even in shallow, clear water. You can often spot the white tips of their fins, and the shadow of a large fish might give away its location.

Anglers targeting bull trout should focus on their predatory nature by using lures or streamer flies that imitate their prey, especially imitating a wounded fish that makes an easy meal.

The bull trout’s relatively large size and the water clarity where they often reside means anglers can spot them in holding water. But they’re remarkably well camouflaged and become almost invisible, even in shallow, clear water. You can often spot the white tips of their fins, and the shadow of a large fish might give away its location.

Anglers targeting bull trout shouldn’t expect high catch rates. The fish are often solitary and well dispersed throughout the river systems, but they can occasionally be found in small schools.

While landing one can be a challenge, their size and weight can sometimes rival salmon and steelhead, and catching a large bull trout in one of Idaho’s cool, clear mountain streams can be an unforgettable experience.

Catch and release tips for bull trout:

- If possible, don’t play the fish to total exhaustion while attempting to land it.

- Keep the fish in the water as much as possible when handling it, removing the hook and preparing it for release.

- When removing the hook, don’t squeeze the fish or place your fingers in its gills.

- If the fish has swallowed the hook, don’t pull it out. Instead, cut the line as close to the hook as possible, leaving the hook inside the fish.

- If a fish is exhausted, hold it in a swimming position in the water and gently move it back and forth until it is able to swim away.

Roger Phillips is the public information supervisor for Idaho Fish and Game.