We’d just finished hiking out of a steep canyon after an afternoon of pretty solid fishing. The hike itself was a bear — straight up a rugged ATV trail several hundred feet. By the time we got to the top, we were sweaty and hot, and the little trout stream was a ribbon of silver shining in the early evening sun.

And the mosquitoes were on to us. Big time.

Chad quickly reached into a pocket of his sling pack and pulled out a little bottle of bug spray. He quickly doused in his exposed arms in the oily concoction and then passed it around. Johnny did the same — a few pumps and then he handed the bottle to me.

“Careful, that’s 100 percent Deet,” I remember Chad saying. At the time, he might as well have said, “I once saw an eagle take a baby rhino and drop it into a snowbank.” I was covered in mosquitoes, and all I cared about was getting them the hell off of me, baby rhinos be damned.

I took the bottle and liberally applied the chemical — known to scientists as N,N-Diethyl-meta-toluamide — and rubbed it haphazardly over my arms and legs. Say what you will about the potential health impacts of Deet (and you might be surprised at how few people have ever actually gotten ill from it), this was not a moment for pondering some far-off disease that might set in because I was careless with bug spray years before. I applied the chemical and gratefully enjoyed a lull in the mosquitoes as we walked the road back to our camp.

Fast forward two weeks.

My son and I were putting fly rods together on the Gibbon River in Yellowstone National Park. As I strung up a rod, the fly line started to disintegrate in my hands.

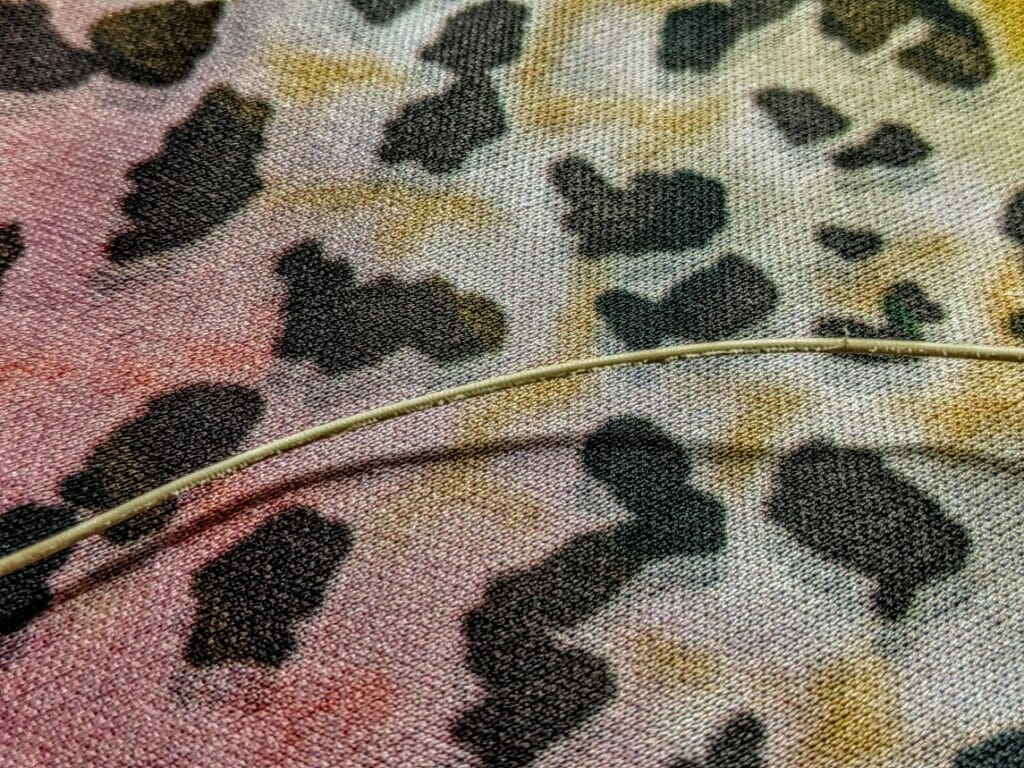

“What the … ” I said, as I pulled more line off the reel. More fly line coating just kind of settled at my feet in a powdery pile of refuse. Then I remembered. Deet may not present the oft-heard health issues we all hear about from our crunchy friends who slather on rosemary oil like butter on an ear of corn, but it does, indeed, take a bite out of fly line. I’m sure, in our haste to rid ourselves of mosquitoes a couple of weeks back, we inadvertently sprayed the repellent on our fly reels. Even a small dose will, over time, eat through the line coating and begin to break down the nylon fly line core.

I was fortunate — I tend to keep a backup fly line for most of my fly reels, and while it was inconvenient to spend time changing out a fly line, it beat having to do stream-side triage on a line that might have quit on me while fighting a fish. But fly lines aren’t cheap, and while I knew Deet could cause problems for them, I’d never actually seen it happen, likely because I’d always taken care to keep the chemical away from my gear.

It was a tough reminder.

There’s not much debate as to the efficacy of Deet when it comes to repelling mosquitoes and other biting insects. Sadly, the best insect repellent on the market is also hell on fly lines. If you’re going to use Deet, apply it well away from your gear, and wash your hands before you touch your fly line.