Fly fishing on lakes in late fall can be a crapshoot. Same thing for chasing trout in the early spring after ice-out.

Often, you’re mingling at the edges of the season where a lake “turns over,” or when surface water that’s been heated by the sun all summer begins to cool and becomes more dense. It drops and the lakes cooler waters that haven’t seen the sun then rise a bit. In the spring, the surface water is heated up again, and the lake’s denser, colder waters drop below the thermocline. Fishing at either time is generally pretty slow.

But on either side of a turnover event, the fishing can be really good for trout that are “suspended” and anticipating a change in water density. Unfortunately, for fly fishers, these fish suspend at varying depths, and while many might try and go after these fish with sinking lines, shooting heads or heavily weighted flies, I’m here to tell you there’s a better way.

Remember when you were kid and you were “fly curious?” I do. I remember tying little dry flies to the leader of my spinning gear and then attaching a bobber about two feet above the fly. I’d cast the rig out and then slowly retrieve it. The “float-and-fly” technique is pretty similar to the old fly and bubble rig you might have tried as a youngster, or before you completely converted fly fishing.

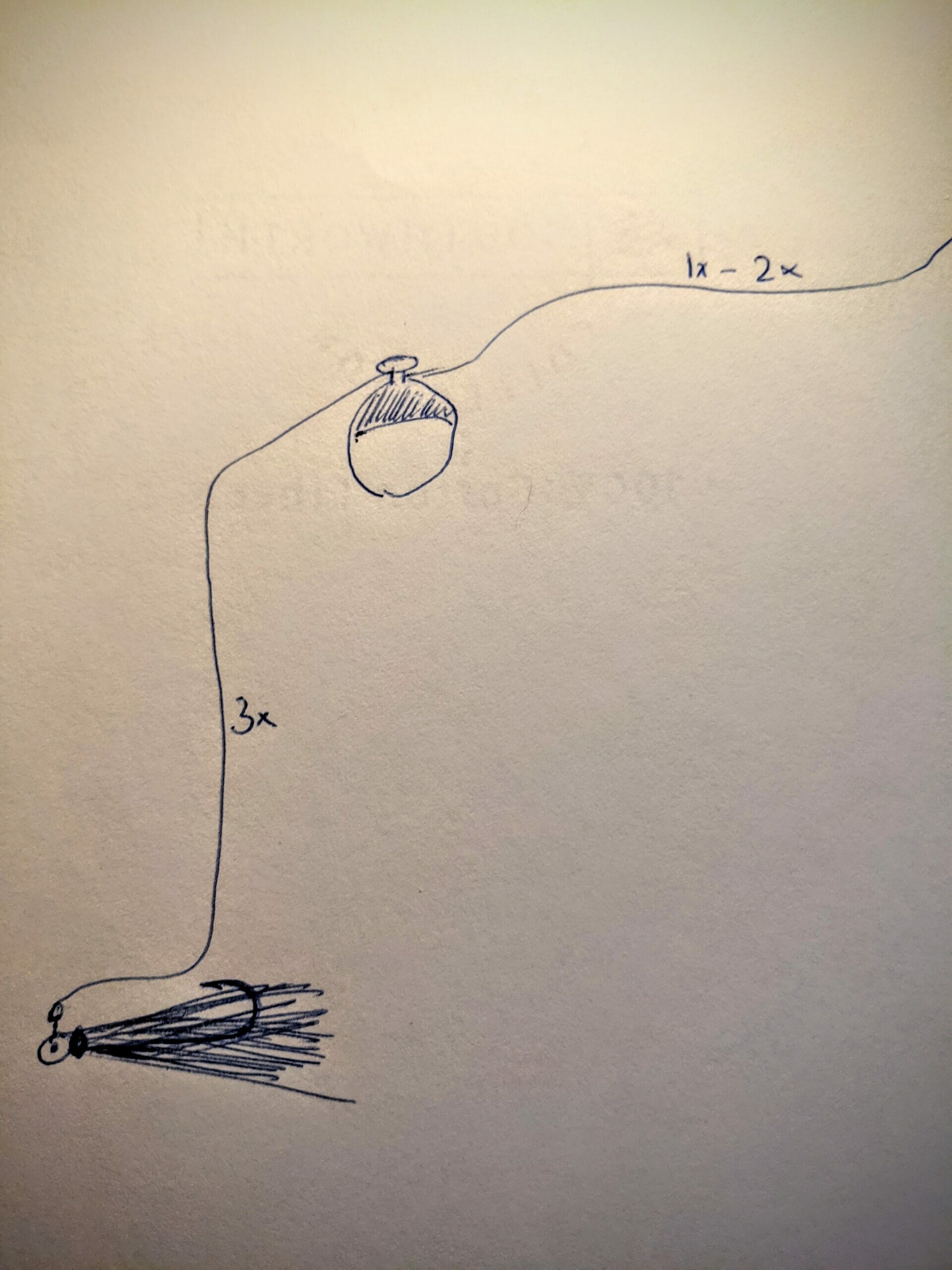

There are subtle differences, however. Today, when I tackle a lake with a float and fly rig, I rarely apply any action to my line at all. Rather, I let the lake’s natural currents and wave action give life to my fly. And the flies I use are different, too. They aren’t traditional trout flies or heavy streamers, but rather flies tied on jig hooks with thinner, wispier materials, like craft fur, or sparse marabou. They are, however, generally weighted, and the “float” I use is usually the biggest Thingamabobber I can find, or, perish the thought, a smaller bobber more commonly used by spin anglers. Some fly fishers use long, slender crappie floats that ride at a 90-degree angler, but tilt when a fish subtly grabs the jig. Preferably, your float will be adjustable — you may have to try several depths before you find suspended fish.

Most flies I use when I’m incorporating the float and fly method are small baitfish patterns — I’ve had good luck with Clousers and Deceivers. Matt Callies from Loon Outdoors ties a great baitfish pattern (see above) that he swears by for float-and-fly fishing in northern California for both winter bass and trout.

The float-and-fly technique works great from a boat, but it’s also a good method to try from a float tube, a pontoon boat, or even a kayak. While it works great for late-fall trout here in the Rockies, I’ve seen it used for winter bass in the South, and even for speckled trout and redfish along the Gulf Coast.

It’s not the most active form of fishing, but when you find the right depth and allow a lake’s natural motion to give life to a suspended fly, the action can turn on quickly. Most importantly, it’s hardly a technical method. Depending on the depth of your below the float, the cast is more of a chuck-and-duck endeavor. Once your fly is in the water, you just leave it there. Occasionally, if there’s no wave action, a little twitch might be necessary, but I honestly only find myself doing this when things are really slow.

Lots of fly fishers prefer moving water — I certainly do. But lakes are great places to chase trout, and they can be great shoulder-season destinations when runoff or skinny water make traditional river and stream fishing difficult. Next time you drag the tube or the pontoon boat out of the garage for some lake fishing, consider the float-and-fly method.