Working to change minds and save wild salmon in the Pacific Northwest

Last week, I visited Lewiston, Idaho, where visitors are greeted with a sign proclaiming, “Thank you for visiting Idaho’s only seaport.”

Lewiston is some 345 miles inland from the Pacific Ocean. What makes it a “seaport” are the reservoirs formed by a series of dams—especially on the Snake River—that turned a wild river into a series of impoundments that make it possible to move grain from Idaho and eastern Washington downriver to true port cities.

But these bathtub-warm, predator-laden reservoirs also decimate wild salmon populations.

Before he became a TU employee, Eric Crawford worked for 20 years as a game warden with Idaho Game and Fish. With the benefit of insights and perspectives from all corners of the state, Eric is working to organize people in Lewiston and the rest of Idaho around the idea that we can create a better future in the Pacific Northwest. We can do that by taking out the four lower Snake River dams to recover the basin’s imperiled salmon and steelhead while also making major investments in transportation, agriculture, water supply, and power.

No one should be left behind in the Pacific Northwest—not the fish that the dams kill, nor the people and communities who depend on the dams. At Trout Unlimited, we understand that, because our members and staff are part of these communities. We have thousands of people in our ranks who live and work in the Northwest and are deeply invested in the region’s quality of life.

Last week, I made the rounds with Eric thanking partners and trying to change minds. First, we met with Dan Johnson, the mayor of Lewiston, a thoughtful person who when the city council advocated for a resolution in support of the dams, asked for one that advocated for dams and salmon.

Later, we met with the staff of U.S. Sens. Jim Risch (R-ID) and Mike Crapo (R-ID). Many years ago, Senator Crapo led a collaborative effort to protect vital habitat in the Owyhee canyons. More recently, Senator Risch was the maestro of an effort to protect nine million acres of wilderness-quality land in Idaho. But both have remained silent on a bold proposal from their colleague, U.S. Rep. Mike Simpson (R-ID) to remove the Snake River dams and make all affected interests whole.

We visited a grain co-op that depends on the reservoirs created by the dams for perhaps 50-65 percent of its traffic. Understandably, its owners want to move their product to downstream markets in a cost-effective and reliable manner.

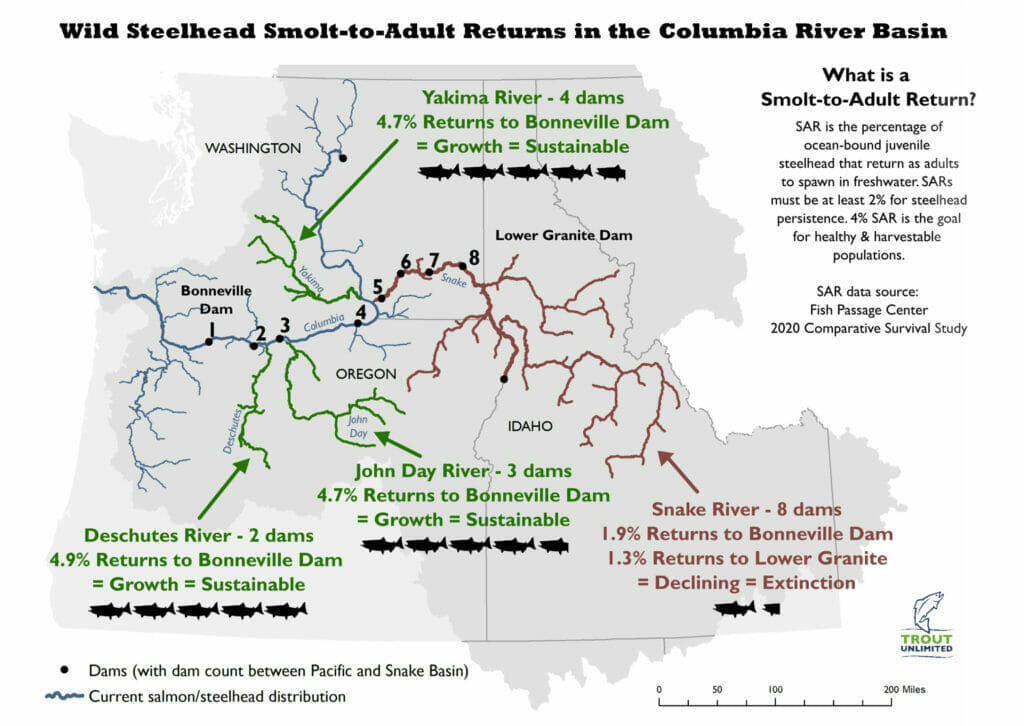

We talked with Shannon Wheeler, vice-chair of the Nez Perce Tribe, who reminded us, “Salmon feed our people and sustain our lands. As the salmon go, so do we.” An old friend of mine who lives in Lewiston and is connected to the dams met me over a few beers, and he tried to blame ocean conditions and predators for the fact that Snake River salmon and steelhead are at one to two percent of their historic numbers. We need only look to two other Columbia tributaries—the John Day and Yakima Rivers—to see that salmon and steelhead can thrive even in current ocean conditions if they are not burdened with passing eight dams.

Through all these conversations, I noticed a remarkable thing.

At the beginning or end of every meeting, we would talk about the pending spring Chinook fishing season. The season can last a few days to a few weeks, depending on how many fish make their way past the four mainstem Columbia River and four lower Snake dams. The fishery is 100 percent hatchery salmon, as wild Chinook harvest ended in the 1970s.

I marveled that no matter how challenging our conversations, the fishing discussion was met with the same amount of excitement and enthusiasm. And yet in the 1950s, before the four lower Snake River dams were built, the Middle Fork of the Salmon River boasted a fishing season that ran not for days or weeks, but for several months, and anglers could keep up to two fish per day. It was a 100 percent wild salmon fishery, with no hatchery fish needed to mitigate losses to the dams.

Recovering salmon and steelhead to the Snake is TU’s highest conservation priority. It will not be easy, as most elected leaders in the Northwest would prefer to avoid the issue. By so doing, they allow wild Snake River salmon and steelhead to circle the drain toward extinction.

As is the TU way, we will work with partners, employ science, and engage all interests—especially those opposed to dam removal—to recover wild Snake River salmon and steelhead.

The reason TU has been so successful at protecting Bristol Bay, taking down the dams on the Penobscot, and protecting places such as the Wyoming Range, is because we bridge differences. In Bristol Bay, we helped unite Alaska Native villages and commercial and recreational anglers. In the Penobscot, we worked with state and federal agencies, tribes, and other conservation organizations to remove two dams and bypass a third. In the Wyoming Range, we connected union workers to hunters and anglers and protected several million acres of habitat for native cutthroat trout.

Restoring the Snake will require that we bridge differences with the people and communities who depend on the dams. We know we can replace the agricultural, energy, and water benefits provided by the system. But the salmon need a free-flowing lower Snake River.

We need Congress to help, and Congress is a reactive body. So, please take a moment to send this action alert to your representatives in Congress. Please also share this QR code with your family, friends, and social media so they can also weigh in on behalf of Snake River salmon and steelhead.

There is little doubt the lower four Snake River dams will come down. They have already outlasted their planned service life and will only grow more obsolete in the coming years. The only questions are, what will replace them, and will it be in time to save salmon for salmon.

It will be a long haul, but these remarkable fish deserve our best effort. We will give it to them.