A 41-year-old promise is yet to be met in the Columbia River basin

Back in 1980, Congress promised that salmon and steelhead would receive “equitable treatment” with the operation of the Columbia River basin hydropower system.

What we are seeing today is far from “equitable.” The fact that wild salmon and steelhead in the Snake River basin are at 1 to 2 percent of their historic numbers demonstrates the need for dramatic reform that must include removal of the four lower Snake River dams. It does not matter what else we do in the Snake River basin; if we do not remove those dams, we are condemning wild Snake River salmon and steelhead to extinction.

To be certain, the federal agency that markets power produced by the Columbia River hydro-system, the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA), and its employees, have made possible a great deal of excellent fish and wildlife work in the basin. Stream-side habitat has been restored, fish passage barriers removed, and some intact habitat has been protected.

For example, Trout Unlimited has worked for over a decade with BPA and a host of other partners to restore the Yankee Fork of the Salmon River (pictured above). This is not so much a stream restoration project as it is a valley reconstruction project. The Yankee Fork was turned upside down by dredge mining from 1940 to 1952. Trout Unlimited and our partners are rebuilding floodplains, river wetlands and stream channels, and restoring the watershed processes that create and maintain habitat for everything from elk and black bears to ospreys, river otters and bull trout.

Chief among the beneficiaries will be steelhead and salmon — but only if we remove the four lower Snake River dams that currently block their ability to migrate to the sea and then return to the Yankee Fork to spawn.

Trout Unlimited and our partners are rebuilding floodplains, river wetlands and stream channels, and restoring the watershed processes that create and maintain habitat for everything from elk and black bears to ospreys, river otters and bull trout.

Or consider the case of Manastash Creek, in Washington’s Yakima River Basin. The Manastash was historically home to imperiled steelhead. Decades of water over-allocation and diversion structures blocked fish passage to over 30 miles of high-quality headwater habitat. Starting about 15 years ago, with funding from several sources — including the BPA, TU and our partners, such as the Kittitas Irrigation District and Kittitas County Conservation District — began to consolidate diversions and acquire water to reconnect the Manastash.

The work culminated with flows being restored throughout the summer in 2015 and the final fish passage barrier being removed in 2016, reopening 30 miles of habitat. Steelhead are now spawning in the stream, and already this year 13 adult steelhead were detected upstream of former barriers.

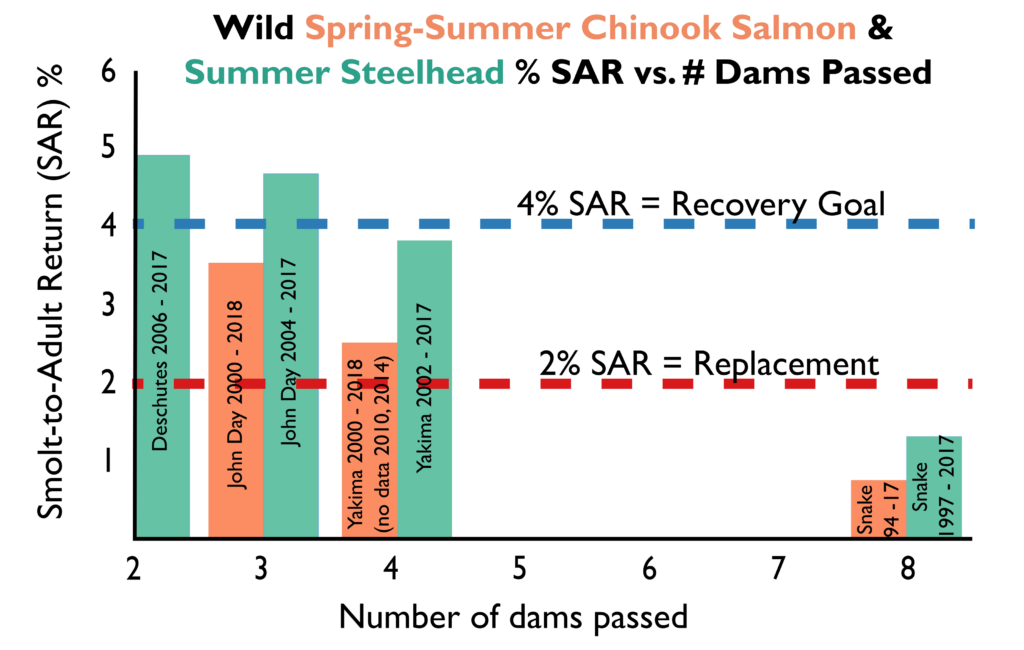

It is fair to assume that steelhead numbers will increase over time in the Manastash, because salmon and steelhead will only have to traverse four dams to return to spawn in the Yakima.

In the Snake, however, the fish must traverse eight dams. The cumulative effect of those additional four dams are devastating to salmon and steelhead, and the mortality caused by the dams effectively negates the potential salmon and steelhead benefits of habitat restoration in places such as the Yankee Fork.

To be certain, there are tremendous benefits to projects such as the Yankee Fork for bull trout, and other resident fish. But, for salmon and steelhead, restoration is less valuable if the fish cannot reach their spawning habitat.

Scientists talk about smolt-to-adult return ratios (SARs) to describe how many adult fish return measured against the number of out-migrating smolts (young fish heading to sea). Recovery goals suggest that 4 percent SARs are essential for healthy populations. After passing four dams, Yakima steelhead approach 4 percent SAR. A 2-percent SAR represents what scientists call “replacement” value. Meaning if you go below 2 percent, you are essentially trending toward extinction. SARs for Snake River salmon and steelhead are well below 2 percent.

If we want salmon and steelhead populations to recover—if we want a return on the significant habitat investments to restore habitat in the Yankee Fork as well as other Snake River Basin watersheds—we will need to increase the SARs of Snake stocks to at least 4 percent.

Make no mistake, BPA’s fish and wildlife program has greatly improved habitat in many places in the Columbia River Basin. But, if the four lower Snake River dams are not removed, the promise of “equitable treatment” will remain unmet, and those wild Snake River salmon and steelhead will become extinct in our lifetime.