What’s next in tackling abandoned mine pollution

It’s been 20 years since the New York Times wrote about how Trout Unlimited, by working with unlikely partners, surmounted hurdles to cleaning up abandoned mines. That story highlighted the ways that federal laws hold Good Samaritans liable for pollution they want to clean up—as if they were the ones who created the pollution in the first place.

Today, we are closer than ever to changing that.

This week, the U.S. House of Representatives finally passed the Good Samaritan Remediation of Abandoned Hardrock Mines Act. The bill allows for 15 pilot projects over a seven-year period to clean up mines that were built a century ago or more and have no owners responsible for cleaning up the waste left behind, including toxic metals like zinc, cadmium, arsenic and lead that leach into our rivers and streams.

The bill, which passed with overwhelming bipartisan support, now heads to the President, who is expected to sign it.

Passage of the bill reflects long-held TU values. We are driven by science. We are resourceful. We meld volunteer advocacy with on-the-ground field know-how and Beltway policy expertise. Most important, we never give up. All of that played a part in getting Good Sam legislation to the President’s desk.

Today, I would like to reflect on what the future holds now that we have (nearly!) concluded our 20-year fight to pass Good Samaritan legislation.

Good Sam on-the-ground

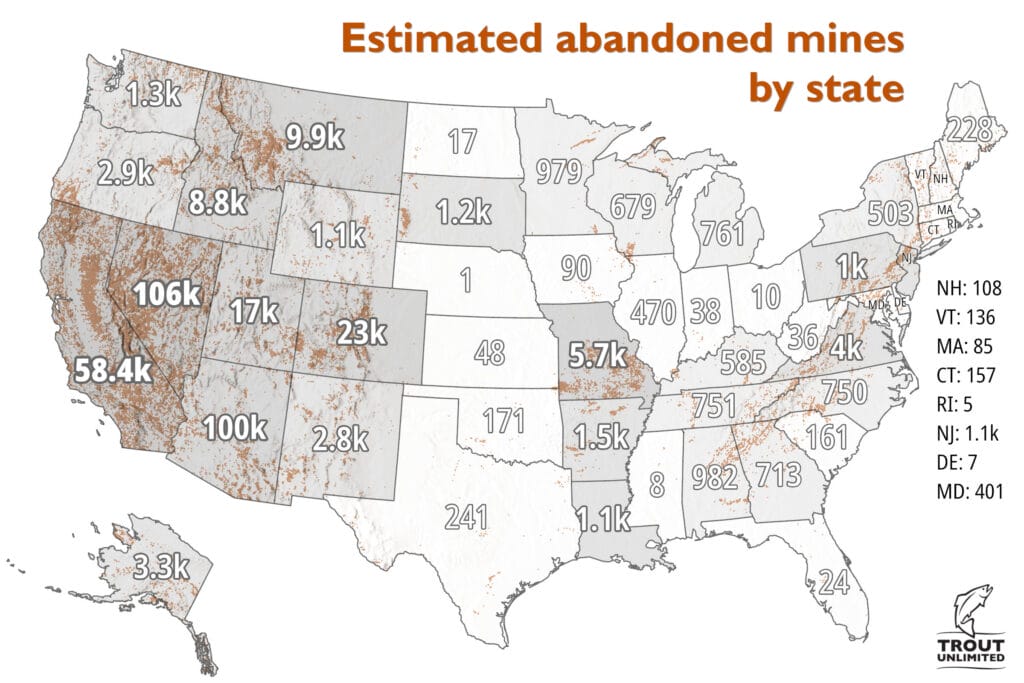

To be clear, 15 low-risk pilot projects over a seven-year period will most definitely not make a material dent in the hundreds of thousands of abandoned mines that dot the American landscape.

What these projects will show is that abandoned mines are a solvable issue. Many people think of abandoned mines as if they are large-scale, multi-million-dollar Superfund sites. As a result, they throw their hands in the air and walk away. The reality is that many, if not most abandoned mine clean-ups, are relatively small-scale construction projects.

The majority of abandoned mine waste, for example, comes from tailings piles. These are the piles of rock that are exposed to oxygen and water, and then their minerals oxidize and leach out in acid mine drainage. The solution is often simply to dig a deep hole, line it with an impermeable barrier, plow the waste into the hole, line it, cover with dirt, replant with native vegetation, and perhaps dig a French drain around the site.

The greatest challenges to cleaning up low risk abandoned mines are not technical. They are financial. Unlike every other commodity that is produced off public lands in the United States, gold, copper, silver, and other hardrock minerals do not have an associated tax or royalty that is used to clean up legacy pollution.

Consider the case of coal. Since passage of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977, and its creation of an Abandoned Mine Land Fund, royalties on the production of domestic coal have allowed for the clean-up of more than $6 billion worth of unsafe and environmentally damaging abandoned coal mines.

Next steps for hardrock mining

America needs domestic hardrock mining to support carbon-free energy production. Critical mineral and rare earth elements such as lithium help charge electrical vehicle batteries. Cobalt helps our cell phone batteries last longer. Tellurium helps promote electrical conductivity through solar panels.

Today, China controls about 60 percent of rare earth minerals, even though the United States has ample supplies on its public lands.

The General Mining Law of 1872, passed when Ulysses S. Grant was President, makes the transition to a clean energy future complicated.

Congress can take obvious steps to ensure robust production of domestic minerals by:

- Establishing a royalty on minerals so we can clean up historic mine pollution, and

- Allowing federal agencies to determine—up front—whether a mine makes sense, and encouraging speedier permit decisions for those that do.

Under the mining law that passed over 150 years ago, professional public land managers may not deny a hardrock mine that its owners can demonstrate will make a profit—even if it would affect a sacred site, community drinking water supply or important fish and wildlife habitat.

Because federal agencies cannot say “no” to a profitable mine, they stall. Professional land managers should be able to deny a mine if it is in a special place, but that denial should happen early in the process, before a mining company has invested tens of millions of dollars in exploration and development.

Now that it has passed Good Samaritan legislation, Congress should take up a combination of mining and permit reform for critical and rare earth minerals.

It is past time for a comprehensive reform that modernizes our mining laws, allows us to provide the minerals necessary for a clean energy future and helps clean up the mistakes of the past.

We should be able to meet the needs of our country while also protecting the social, cultural and ecological values that make America great.