Why folks at Trout Unlimited care so much about a shad fishery up the road from the Washington monument

Everyone has a special place.

When I was going to high school in Jersey City, one of mine was the abandoned docks below the Hoboken train station. To get there, I had to sneak past darkened Amtrak offices before dropping down a hidden series of decrepit stairs to a series of abandoned docks. The water was right at my feet, and I would wonder what I could fish for if I snuck in a rod. It was a scene out of “Planet of the Apes.”

For the past 30 years, my special place has been Fletcher’s Cove in Washington, D.C. As with that abandoned port in Hoboken, every time I go, it is both a coming home and an entry into a place time seemed to have forgotten.

A “Batcave” tunnel leads underneath the C&O Canal and into the Fletcher’s parking lot. When they were younger, my sons loved to roll the windows down and scream as we drove through. I will admit I still do that, sometimes.

Fletcher’s sits on the banks of the Potomac River, and every spring, hundreds of thousands of herring and shad make their way up the river from the ocean to spawn. We have done extensive work with over 400 farmers in the headwaters of the Potomac where trout thrive, but in D.C., it is not a coldwater fishery. That said, it figures heavily into the relationship-building Trout Unlimited does in the nation’s Capital.

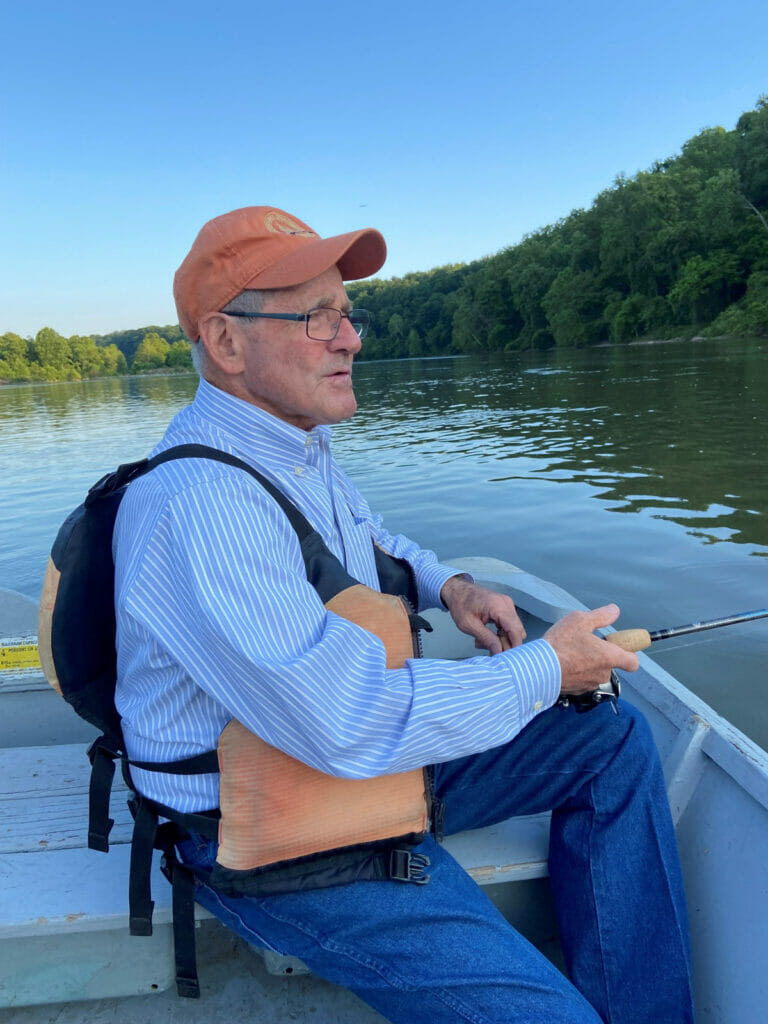

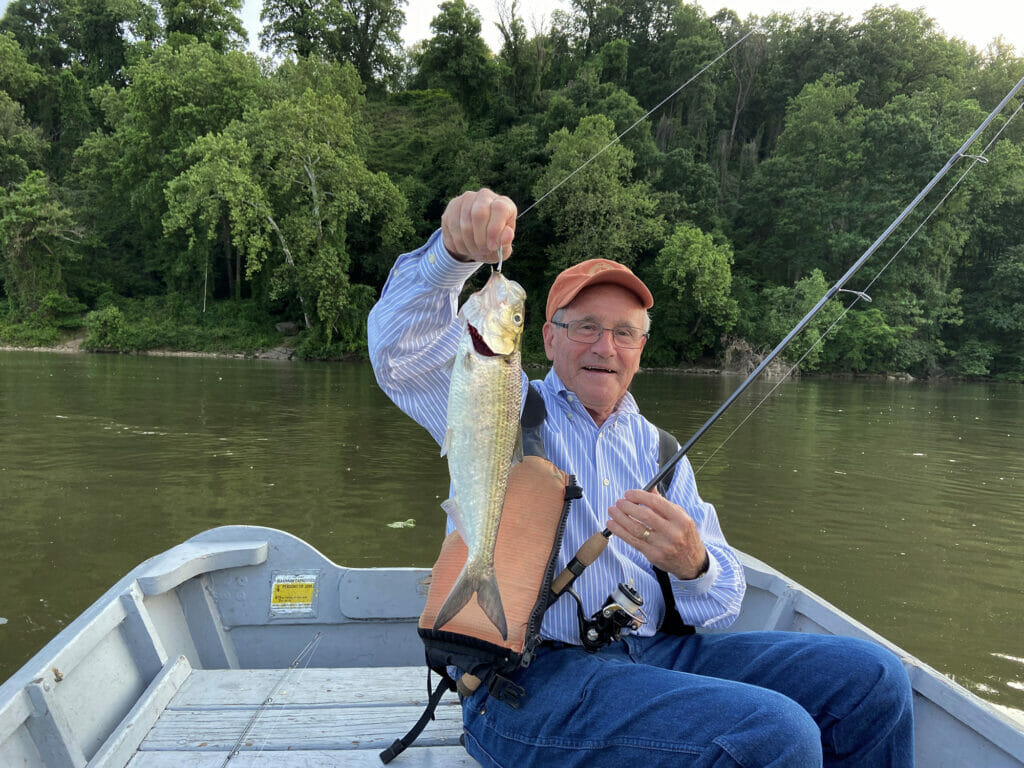

Every year, I take agency heads, partners, volunteer leaders, and other VIPs out to fish for shad. TU staff call it “rowboat diplomacy.”

Just this week, I was out with U.S. Sen. Jim Risch (R-ID), who in 2009 worked with a group of us to protect nine million acres of wilderness lands in his state, and who today is working with TU and U.S. Sen. Martin Heinrich (another Fletcher’s veteran) to pass Good Samaritan abandoned mine cleanup legislation. Sen. Risch was blown away that such a fishery existed within the city limits.

“Everyone comes here,” Ray Fletcher, the last of three generations of his family to run the concession, once told me. “Presidents, senators, cabinet members, they all come to the river, eventually.”

Ray used to work out of the concrete block boathouse. Marks painted on the walls designate the height of floods from famous hurricanes and provide a measure of the history of the place.

Jim Cummins is the biologist to thank for this amazing fishery. He helped to bring shad back to the Potomac. From 1995-2002, he led a program that netted spawning shad near the mouth of the Potomac, raised shad fry and reintroduced them upstream of Fletcher’s at Great Falls, Maryland, the end of their migration in the Potomac from the Atlantic Ocean.

Schools of striped bass and avian predators such as cormorants, bald eagles and osprey follow the shad and other smaller fish. One morning this spring, five ospreys began hunting the waters below as soon as the sun rose over the trees.

There are three types of shad. Gizzard shad make quite a ruckus on the surface of the water. Many trout anglers get fired up when they see the “gizzies” break the surface, but they generally will not hit a fly or lure. The hickories and Americans, on the other hand, hit lures and flies, and they hit them hard.

We cast full sink lines with shad darts to these “freshwater tarpon.”

We fish for the shad from a fleet of largely wooden boats. In recent years, Alex Binsted, who runs the concession, has been forced to supplement the fleet with some aluminum boats. The Friends of Fletcher’s Cove has also donated several boats to supplement the fleet.

We jig for stripers and white perch in the late winter and early spring and fish for shad through May. June brings a fine schoolie striper bite, and then the frighteningly fun gar fishery commences. For those wanting to go deep, invasive blue catfish abound throughout the year. Another invasive species, Snakehead can be caught with surface lures later in the summer.

A few weeks ago, at the height of the hickory shad run, I was fishing with my friend, Chris, who works for the Forest Service. After about 30 minutes, he looked at me and said, “I think that is the first cast I haven’t had a fish.”

As good as the fishing is, and it can be truly epic, it is the people who make Fletcher’s so special. Alex took his first steps at Fletchers and is among the fishiest people I know. Many of his present and former employees are also hard-core anglers. Bobby Smith, for example, is known to sleep in his car in the parking lot to get on the water by 3 a.m.

Former Fletcher’s employees often get involved in conservation. Josh Cohn, for example, works for the Ocean Conservancy. Chris Campo is a biologist for Washington, D.C., and leads efforts to introduce the river and its angling opportunities to residents. Dan Ward has worked at Fletcher’s since 1969 and is the resident historian and friendly face behind the counter.

On a recent morning, I saw Gordon Leish and Paula Smith heading downriver for white perch, and recalled the time when I first moved to Washington and was trying to figure out how to fish the Potomac. Gordon made me a chart that listed where to go, and what to fish for at every month of the year in the D.C. area. It remains a prized possession.

Mark Binsted and Mike Bailey may be the best American shad and striped bass anglers, respectively, on the river. They recruited me and Rob Catalanotto, a former Fletcher’s employee who now works for the Trout Unlimited government affairs team, to join Friends of Fletcher’s Cove (FFC).

FFC works to ensure that Fletcher’s remains accessible to the public. In the 1960s, thousands of truckloads of fill were dumped upstream of Fletcher’s as part of the Dulles airport expansion. What had been a series of wetlands became a wide, half-mile long earthen impediment to the river. During high water, the river used to flush out the sediment in the cove. Today, during a flood, the water rises, and the sediment drops out and piles up in the cove. If it continues, this prized access to the river will be cut off.

FFC is working with a host of partners to fix the problem. In the short run, we need to dredge out the cove to maintain access to this premiere fishery. In the long run, we are working with an array of state, federal, and non-profit partners to develop a long-term ecological solution to recover the natural functions of the river. (FFC is also working to introduce kids from Washington to one of the best kept secrets, in a city not known for keeping secrets).

Anglers are notorious liars and exaggerators, but it is not an overstatement to say that the Potomac is the best urban fishery in the nation, and it is not a lie to say that recreational fishery is at risk if we are not able to recover the access to the river.

For many years, TU has been a fiscal sponsor to Friends of Fletcher’s Cove. Given its proximity to our home office and its role in helping us introduce the wonders of fishing to the nation’s decision-makers, it remains a special place for us. It may not be a trout or salmon fishery, but I hope you will join me in supporting Friends of Fletchers Cove and help to maintain this magical place that time forgot.