“It is our collective opinion, based on overwhelming scientific evidence, that restoration of a free-flowing lower Snake River is essential to recovering wild Pacific salmon and steelhead in the basin.”

So reads a remarkable letter recently sent to the governors of Oregon, Washington, Idaho and Montana by 10 of the finest and most-respected salmon and steelhead scientists in the world.

The letter continues, “Every Snake River salmon and steelhead population is listed under the Endangered Species Act (ESA), with recent returns consistently below the threshold needed to avoid extinction. Pacific lamprey, another anadromous species of major significance to tribes and the freshwater and marine ecosystem, have also declined precipitously.”

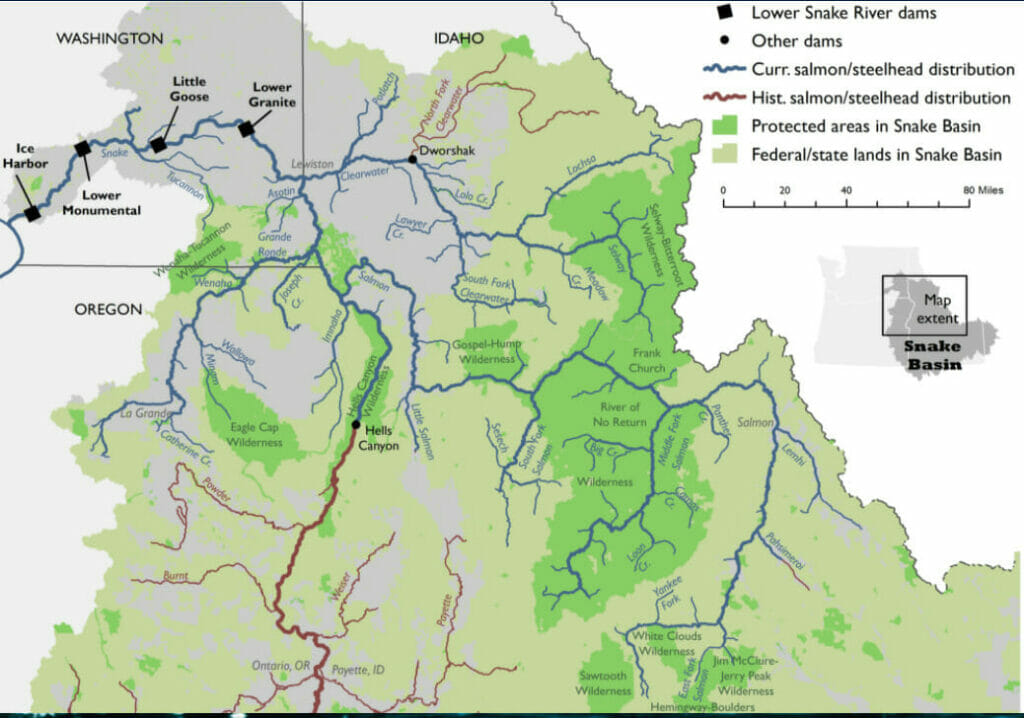

The salmon populations in Idaho were so abundant that in the 1950s, before the construction of the four lower Snake River dams, recreational anglers on the Middle Fork of the Salmon River could catch and keep up to two salmon a day over a season that stretched months. That all changed when we inserted the concrete monoliths that are the lower four Snake River dams smack dab in the migration corridor of these remarkable fish that connect the mountains of Idaho to the waters of Pacific Ocean.

Today, populations of salmon in the Middle Fork—some of the finest salmon habitat in the world—are at about 1 percent of their historic numbers. This is even though we have spent over $17 billion as a nation to help recover Snake and Columbia river steelhead and salmon.

The dams’ advocates often argue the salmon’s problems are overharvest, poor habitat and hatcheries. Harvest, however, has been sharply curtailed. Idaho brags five-star wilderness-quality habitat. Hatcheries can manufacture fish in concrete tanks but create a false sense of abundance (comprising 80 percent of the fish in some years) and hurt wild fish.

Lately, some have tried to point to ocean conditions as the reason for the decline of Northwest salmon. Climate change is affecting the ocean, and conditions are deteriorating in both fresh and salt water. As the scientists’ letter says, “Ocean conditions fluctuate” and salmon have evolved with changing ocean conditions for eons. And while modifying the ocean is not within our immediate control, we have modified their migratory path. The Snake River Basin in Idaho contains the best remaining spawning and rearing habitat for salmon and steelhead in the lower 48. The fish need safe access to these habitats so that populations can thrive when conditions are good and survive poor ocean conditions.

The scientists say that “dam breaching is the essential cornerstone of a comprehensive, effective recovery strategy.” They also point out that “the weight of scientific evidence demonstrates there is no chance of restoring abundant, healthy and harvestable Snake River salmon and steelhead with the lower Snake River dams in place.”

As with most conservation issues, we do not have to choose between recovering salmon and maintaining and improving the socio-economic well-being of those whose livelihoods depend on the dams.

The scientists conclude their letter by asking for the four governors’ “leadership to develop a comprehensive solution that includes removing the lower Snake River dams so that the extraordinary potential of the Snake River Basin for people and fish can be realized.”

With a little leadership and creativity, we can extend irrigation infrastructure to withdraw water from a free-flowing river. We can replace barge traffic on the reservoirs behind the dams with rail. We can find replacement power to make up for the relatively small amount provided to the region by the four lower Snake River hydropower dams. We can create economic opportunity for the towns dependent on the reservoirs. We can make improvements to the power grid to assure the reliability of affordable power to cities and towns across the Northwest.

We can use our creativity and ingenuity to make whole all the various communities of place and communities of interest dependent on the four lower Snake River dams. The one thing we cannot do is expect Snake River salmon to flourish when they have to pass through 140 miles of predator-filled slackwater reservoirs and over four concrete walls to get to home. For millennia, salmon have reared in the mountains of Idaho, been pushed by spring flows to the ocean, grown, and then returned to the very streams where they were born to continue the cycle.

The science is clear. The lower four Snake River dams must come down.

Chris Wood is the president and CEO of Trout Unlimited.