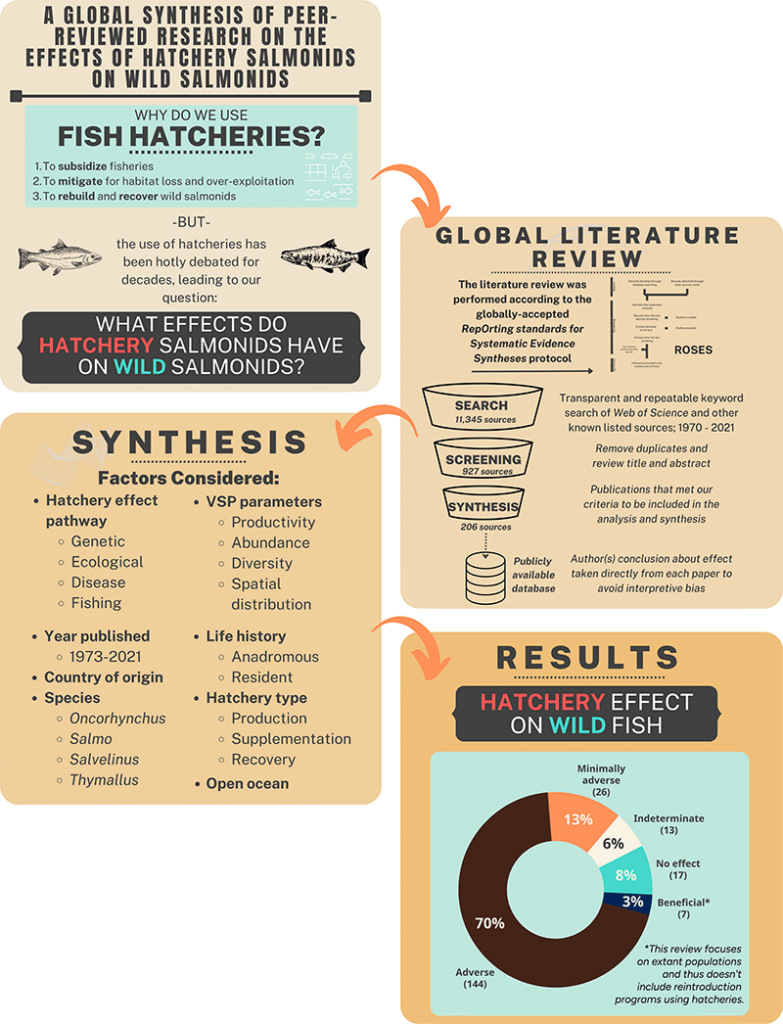

A literature Review led by Trout Unlimited shows over 80 percent of global, peer-reviewed research on the topic has found an adverse effect on wild salmonid populations in freshwater and marine environments.

Across the world, hatcheries have been used for over a century to produce salmon, trout, and char to support harvest opportunities in commercial, subsistence, and recreational fisheries; mitigate for habitat loss and overfishing; and aid in the recovery of wild salmonid populations. These programs vary widely in size and purpose, from targeted efforts to prevent extinction or reintroduce extirpated populations, to large-scale fishery-focused production programs releasing fish in freshwater or directly into the ocean. Some draw upon wild, native fish for broodstock and others have introduced non-native species or non-local stocks into watersheds.

While hatcheries can enable fisheries that were lost when dams were built and habitat degraded, or create popular fisheries where they hadn’t previously existed, they can also harm wild salmonid populations through genetic impacts on fitness and diversity, and ecological impacts such as increased predation, competition for food and spawning sites, and susceptibility to disease. Hatchery fish also have lower survival rates and produce fewer offspring in the natural environment than their wild counterparts, which over time diminishes their effectiveness.

While the risks and limits of hatcheries are broadly acknowledged in the scientific research, many communities have come to depend on these programs to support fishing opportunities where fisheries might not otherwise exist due to the loss of wild salmonid populations. The tension between the scientific evidence and reliance of managers and fishing interests on hatcheries has led to controversy and confusion around their widespread use.

To provide clarity to this critical conversation and serve as an important resource for decision-makers, resource managers and the public, a team of researchers brought together by Trout Unlimited recently published a new global review examining over 50 years of peer-reviewed scientific literature on the topic. The effort included development of a publicly accessible database of key research and a synthesis of the findings on the impacts of hatchery produced salmon, trout, and char on wild salmonid populations in both freshwater and marine environments.

Their new paper, “A global synthesis of peer-reviewed research on the effects of hatchery salmonids on wild salmonids” was published and is openly available in the peer-reviewed journal Fisheries Management and Ecology.

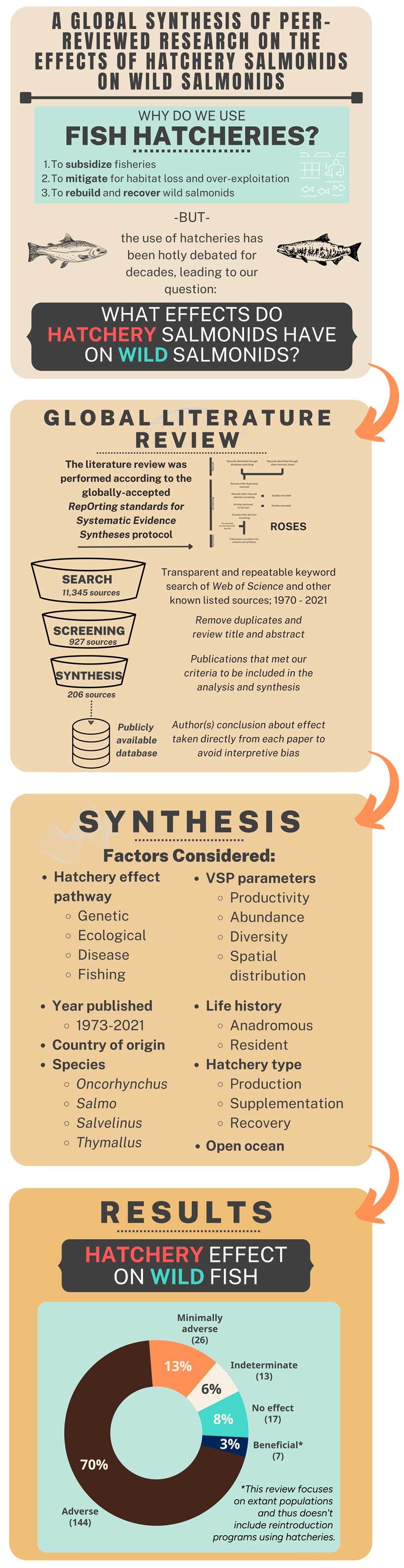

In their examination of the global literature, the coauthors found that over 80% of peer-reviewed research concluded that hatchery releases have had an adverse effect on wild salmonid populations, while just 3% showed a positive impact.

A Comprehensive Approach

The new literature review and synthesis was led by fisheries scientist John McMillan and TU’s senior scientist, Dr. Helen Neville. McMillan began the work four years ago while he was the Science Director for Trout Unlimited’s Wild Steelhead Initiative, building on work by fisheries biologist Brian Morrison, one of the review’s coauthors. (Since February of 2022, McMillan has been the science director for The Conservation Angler). McMillan and Neville invited a team of prominent American and Canadian fisheries scientists to contribute and ensure a thorough approach, including leading experts in salmonid genetics, ecology, and ocean food web impacts.

“It is important to take stock of the totality of existing information from time to time, particularly for complex topics that span several species and multiple continents,” explains McMillan. “Considering the volume of research and the tendency of managers and scientists to operate in regional or species-specific silos, we thought there was value in conducting a global literature review to fully evaluate the body of literature and determine what the weight of evidence says about effects of hatchery salmonids on wild salmonids, and ultimately, to create a database that allows people to easily access information they may not have been previously aware of.”

From the beginning, the team took a transparent, comprehensive approach. Following a globally accepted framework for scientific literature review and synthesis, they first established a rigorous protocol to guide the evaluation of 11,320 peer-reviewed publications captured through a broad key-word search.

The coauthors then used a decision tree to screen the research papers for relevancy based on whether the studies focused on hatchery salmonid influences on the viability (i.e. VSP – Viable Salmonid Population – parameters) of wild populations via genetic, ecological, disease or fisheries effects, including the impacts of large-scale hatchery releases into the North Pacific Ocean. Using these criteria, they eventually narrowed down to 206 key articles published between 1970 and 2021 for inclusion in the literature review.

These representative publications were assembled into a new, publicly available database that will continue to be updated by science staff at Trout Unlimited. Helen Neville explains, “Our goal was to provide an open and transparent resource summarizing the global research that others could draw from and that could be updated in the future as new science comes out.”

The selected papers were grouped by year, country, salmonid species, life history (migratory vs. resident), and habitat type. The coauthors then reviewed the results of the research, classifying the outcomes as “adverse,” “minimally adverse,” “indeterminate,” “no effect,” or “beneficial.” Importantly, these conclusions were based solely on the results as stated by the author(s) of each original publication.

These results were further divided by the hatchery program types, which included production, supplementation, and recovery programs; the effect type: genetic, ecological, fishing, disease, or a combination; and whether this impacted the productivity, diversity, spatial distribution, or abundance of wild populations. Finally, the authors also reported on publications evaluating hatchery effects in the ocean and summarized the general findings.

The Literature Review’s Findings

In the end, the coauthors found that 83 percent of the publications reviewed reported some level of adverse effects on wild salmonids from hatchery salmon, trout and char. A small percentage of the literature reviewed found beneficial effects (3 percent of the publications included), which were primarily associated with recovery hatcheries aimed at providing a short-term boost to highly depleted wild populations threatened with extinction.

The coauthors note that the new paper does not consider instances of successful reintroductions of extirpated salmonid stocks, as the focus of the literature review was on research documenting impacts to existing wild populations. For example, research on the hatchery programs being used to reintroduce salmon above Grand Coulee Dam on the Columbia River would not have been included or evaluated.

When sorting the literature, the authors found the majority of studies focused on Brown Trout, followed by Steelhead, Chinook Salmon, and Atlantic Salmon, with publications spanning 22 countries across the globe. Most of the studies reviewed focused on migratory species in freshwater habitat, while 23 studies focused on the impacts of hatchery fish on wild salmonids during their time spent in the ocean.

Research focused on large-scale, production hatchery programs dominated the literature, while less than a quarter of the studies focused on supplementation and recovery programs.

“We found that the vast majority of studies reported some level of adverse hatchery effects, which echoes similar prior reviews by Miller et al. (1990) and Araki and Schmid (2010),” explains McMillan. “The consistency in results over time suggests the science has matured to a point where we have a true, long-term understanding that hatchery salmonids harm wild salmonids much more often than benefit when they interact in nature.”

Unsurprisingly, impacts from fishery-focused production programs, which typically release large numbers of fish and use highly domesticated broodstock, had a high rate of adverse effects on wild salmonid populations, with 91% of the papers evaluating these programs falling in the adverse or minimally adverse categories.

Most publications considering supplementation hatchery programs, which integrate wild fish into the broodstock to varying degrees and typically have smaller and more controlled release groups, also found negative impacts on wild salmonid populations, though not as high of a percentage as the production programs. The literature reported 64% as having adverse effect, 17% with no effect, and 7% concluding a beneficial effect on wild populations.

Recovery hatchery programs, which are typically managed under a strong scientific framework and tend to be highly monitored, unsurprisingly reported the lowest levels of adverse effects on wild populations: 30% were found to have adverse effects, while 41% were either indeterminate or had no effect, and 29% provided benefits to wild populations.

Looking at the literature broadly, the coauthors found that the vast majority of studies focused on genetic effects between hatchery and wild fish, and that these papers primarily focused on impacts to diversity of wild salmonid populations. Of these, 84% of genetic studies focused on diversity reported adverse effects on wild populations while only 3% reported beneficial effects.

In addition to these studies of ‘traditional genetics’, the coauthors discussed, but did not include research on the emerging field of ‘epigenetics’—where changes occur through environmental influences on how genes are expressed, not through the genetic code itself – which is increasingly recognized as an important pathway of influence on salmonids in hatcheries (Koch et al. 2023).

Following the papers on genetic effects, the ecological impacts of hatchery salmonids received the most attention in the literature. These impacts were the sole focus of 60 studies, with 73% of these finding adverse effects on wild populations. These ecological effects were most often expressed through hatchery fish preying on wild salmonids or competing with wild salmonids for food or spawning sites.

Ocean Hatchery Impacts and Further Research Needs

There is a growing awareness among scientists that the ecological impacts of large-scale hatchery releases of Pink and Chum Salmon in Alaska, Russia and Japan are affecting wild salmonid productivity in the Pacific Ocean. The literature review included 23 publications on marine hatchery impacts and the coauthors identified the topic as one needing further research. The included papers focused primarily on the increase in competition in the ocean food web, which impacts wild salmon populations in the form of reduced growth rates, body size and fecundity, delayed maturation, lower productivity and survival, and fewer returning wild fish.

The included studies focused on hatchery effects on local populations in marine waters and the total salmon density effects in the ocean. Similar to the overarching results of the review, 77% of these studies showed adverse effects on local wild populations, while an overwhelming 90% of the studies looking at total salmon density in the ocean found adverse effects on wild salmonids.

Dr. Greg Ruggerone, one of the literature review’s coauthors and a leading researcher on the ocean impacts of hatchery releases, explains, “The key question is: does the ocean have a limited capacity in terms of numbers of salmon it can support? If so, then industrial scale hatchery production can have unintended effects on wild salmon. About a quarter of the total number of salmon returning from the ocean are hatchery salmon (mostly pinks and chum), but 40% of the immature and mature biomass of salmon in the ocean are hatchery origin (again, mostly chum and pinks). Unfortunately, nobody has manipulated hatchery production as an experiential approach to test the hypothesis, but the alternating-year pattern of Pink Salmon abundance provides a natural experiment and strong evidence for competition and food limitation at sea.”

“In a new publication cited in the hatchery literature review, we examined studies of Pink Salmon interactions with other salmon and marine species and found consistent and strong support for food limitation at sea, indicating that industrial scale hatchery production has unintended effects on the growth and survival of all Pacific salmon species. These adverse effects on wild salmon, including those from the Pacific Northwest, are widespread because salmon migrate thousands of miles at sea and interact with distant hatchery populations.”

Beyond the need to further consider the impacts of increased competition in the marine environment, the literature review highlighted the need for further research into the impacts of diseases and parasites carried to wild salmonid populations by hatchery fish, and the impacts on depressed wild stocks in fisheries targeting plentiful hatchery fish. While both factors are broadly understood to have negative impacts on wild fish, they are poorly represented in the literature. Only two studies and a review focused on disease and parasite effects and three studies looked at fishery effects.

The coauthors also identify a recognized need to better understand how the hatchery environment itself changes the expression of genes in the salmonids reared in these programs. As mentioned above, the field of “epigenetics” may be the key to understanding many of the physiological, physical, behavioral and life history changes observed in hatchery fish.

Dr. Louis Bernatchez, a coauthor of the literature review and Canadian research chair in Genomics and Conservation of Aquatic Resources at Laval University in Québec, Canada, explains, “For more than a century, hatcheries have been used as a major management tool with the main goal of enhancing population abundance of salmonid fishes worldwide. But as demonstrated in this synthesis, decades of research have now made it clear that the mere benefit of increase in census size is, most of the time, more than offset by adverse effects of interbreeding between wild and stocked fish on the ecological and genetic integrity of native populations.”

“Among the main documented adverse effects — loss of genetic diversity and therefore of evolutionary potential — is of major concern given the fast pace of environmental changes that wild populations must cope with. To enhance our knowledge of the full extent of hatchery impacts and improve their practice, new research must focus on less investigated aspects, such as the impacts of hatchery rearing on how genes are expressed, or the role of different kinds of genetic variation on the adaptive potential of wild populations.”

A Critical Scientific Resource for Managers and the Public

The results of this global scientific literature review clearly affirm that salmon, trout, and char hatcheries present a significant risk to wild salmonids through ecological and genetic impacts, even when using more modern supplementation hatchery programs and practices.

Their use can hinder wild salmonid recovery efforts and harm wild populations when programs aren’t designed or managed properly. In particular, the research points to the outsized negative impacts of large-scale production programs and raises serious concerns about the food web impacts of large numbers of hatchery fish in the ocean.

The review also points to key examples where a small number of recovery programs guided by the best available science and rigorous monitoring have been shown to minimize negative impacts, or even benefit, wild (i.e. natural origin) salmonid populations. These programs are notable exceptions to the review’s broad findings, but their inclusion is important because they offer insights into how hatchery management practices can be improved to be more effective and reduce adverse impacts on wild populations.

The use of hatcheries is a complex topic, one that must balance social, cultural, ecological, and economic factors. Ideally, this literature review, synthesis of findings, and public database becomes an evolving resource to help inform worldwide wild salmonid management, protection, and recovery efforts as these populations struggle with the growing impacts of climate change and try to take advantage of ongoing efforts to reconnect and restore habitat.

“Our findings closely mirrored, and thus corroborated, earlier, more geographically limited reviews. They also reveal several key areas where more recent science, particularly related to competition in the ocean and the fast-moving field of genetics, has advanced our understanding of how hatcheries impact wild salmonid populations,” Helen Neville explains. “Informed by the global science, we hope this work will motivate and support a deeper consideration of when and where hatcheries may or may not be an acceptable or effective tool, and how we can minimize harmful impacts to wild salmonid populations when they are justifiably used for compelling reasons.”

“Although this report is global in nature, we recognize that hatcheries play a significant role in specific regions where wild salmon and steelhead remain on the brink of extinction because of habitat degradation, including places where dams have drastically reduced wild production,” Neville continues. “In such places, hatchery salmon and steelhead, for instance, often serve as a vital lifeline to the lives, cultures, and well-being of Tribal Nations, and Trout Unlimited looks forward to continuing to work with Tribes and others toward essential actions, including dam removal, that can recover healthy and harvestable populations of wild salmon and steelhead. But, as this global research synthesis makes clear, we must take care to operate hatcheries in a manner that does not prevent wild salmonids from recovering.”

Acknowledgement: The vast majority of project funding for the lead author was provided by Trout Unlimited, with additional funding via the Wild Steelhead Coalition and The Conservation Angler.

Author Bio: Gary Marston is the science advisor for Trout Unlimited’s Wild Steelheaders United. He completed his master’s degree at the University of Washington studying the ecological interactions between rainbow trout and steelhead on the Olympic Peninsula. Before joining Trout Unlimited, Marston spent eleven years working for the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, focusing on hatchery/wild interactions, steelhead marine survival patterns, life history diversity, and food web dynamics between juvenile steelhead and rainbow trout.