The relationship between fish, people and water in Nevada is a sordid tale, with Walker Lake, nestled in the western corner of the state, as a particularly interesting character.

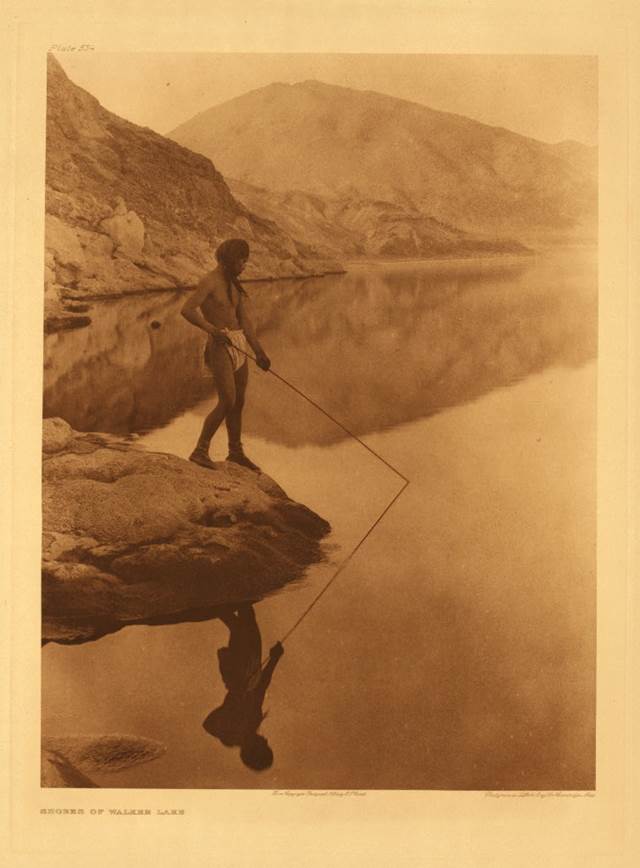

Walker Lake historically sustained one of the few lake-form populations of Lahontan cutthroat trout, growing large predatory trout similar to the much-famed Pyramid Lake just to the North. Native Americans fished here with gill nets, bone hooks and spears; in the late 1800s the lake supported a commercial trout fishery, which later turned into a prized recreational fishery.

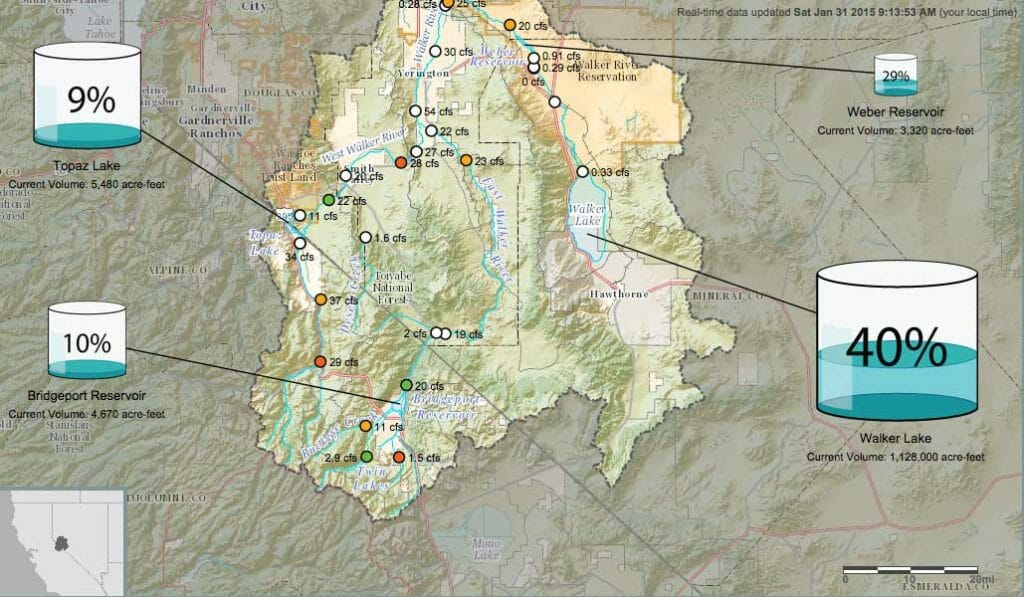

Since ranching and agriculture took hold in the valley in the mid-to-late 1800s, much of the water from the Walker River – which drains two major basins of the rugged eastern Sierra Nevada Mountains before meandering through several flat, wide agricultural valleys and into this desert terminal lake – has been diverted to irrigation, to the extent that in some years no water actually reaches the lake. The water level of the lake has declined so drastically (over 150 feet!) that as of a few years ago the lake can no longer support trout due to its high salinity.

Climate change is also taking its toll. Drought has hit this part of the west so hard it can be seen by NASA satellites, and the latest Drought Monitor data for January have this corner of Nevada parked soundly at ‘extreme’ and ‘exceptional’ drought.

Walker Lake is now only 40 percent full, and the two reservoirs to the west are at only 9-10-percent capacity. Not surprisingly, hydrographs for the two agricultural valleys in the basin have declined by an average of 8 and 12 feet per year, due to a combination of reduced stream flow from drought and an increased reliance on groundwater pumping – i.e., more straws in the ground.

In response to this crisis, the Nevada State Engineer just ordered a 50 percent curtailment of supplemental irrigation rights in the basin, meaning many people relying on farming for their livelihoods are in dire straits. But there are several glimmers of hope, even in this Draconian situation.

For one, partners like the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, which oversees the Walker Basin Restoration Program established by Congress in 2009 (thanks in large part to Sen. Reid), are developing innovative tactics like leasing or buying water rights from willing landowners and switching fields over to more water-friendly crops. They are making slow-but-sure progress in a highly contentious cultural environment, to improve the situation for the people while inching more water toward the lake.

Three thousand feet up, in the high-elevation headwaters of the Walker River, Trout Unlimited is working with partners to restore Lahontan cutthroat trout to high-quality habitats in their historic range; our hope is that these areas may serve as refugia where the fish can persist as climate change gets worse.

If drought conditions continue along the current trajectory there is no easy fix in sight. The goal of providing water and income security for the human population of the region, while increasing flows into the lake to restore Lahontan cutthroat trout will require increasingly complex negotiations. But hopefully these collective efforts will one day restore the lake back into its once magnificent state, where it can again support Lahontan cutthroat trout.

Helen Neville is a senior scientist for Trout Unlimited. She works from Boise, Idaho.