Reflections on climate change and its impact on future generations

By Ann Foster

Our cottage sits wedged between a busy state route and Paradise Creek. Out in front cars whiz by in a steady stream as locals make their way into town to catch busses on the daily commute to jobs in the metropolitan areas of New Jersey and New York.

Most of the commuters are totally unaware of the piece of paradise that lies 300 yards behind the tree line bordering the road. Yet they will make no fewer than 10 stream crossings during that short drive — passing over and next to some of the most abundant and pristine coldwater fisheries in the northeast United States, all clustered here in the Brodhead watershed.

While many are unaware of the wonders just out of sight as they focus on getting to and from work, I’m proud my children and grandchildren are not among them.

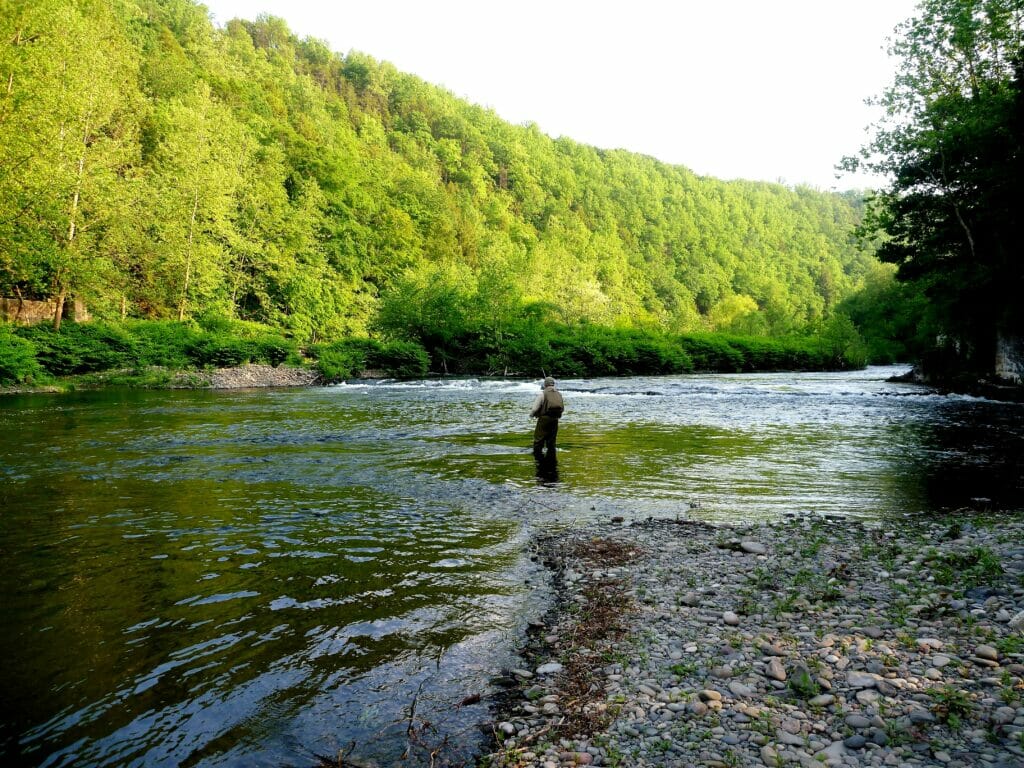

Unlike the busy commuters, my family has discovered the rushing waters of Paradise Creek, tumbling and cascading down in riffles and runs through rhododendron groves and stands of white pine and hemlock. We’ve explored its headwaters of Yankee Run, Tank Creek and Devils Hole Creek (an exceptional value wilderness trout stream) and stood on their banks discussing the stewardship and commitment that will be necessary to protect and sustain them.

As my grandchildren grow older we are having longer and more detailed discussions about the threats to our beloved waters and those around the planet.

After tumbling over spectacular step-stair falls, Paradise Creek gathers up waters from the Swiftwater and Forest Hills Run and continues its journey another five miles where it spills into the Brodhead Creek and the Delaware River beyond. Many of these waters have the highest water quality designation in the state; designations that afford them special protections.

Places like this aren’t unusual in the Pocono Mountains of northeast Pennsylvania. Whether you pass through on busy Interstate 80 or travel secondary state routes to avoid highway congestion, a plethora of exceptional value coldwater fisheries and pristine headwater mountain streams aren’t far away, often unbeknownst to the busy traveler.

Sure, there are more majestic places to fish; places with snow-capped mountains and clear rivers flowing for hundreds of miles far removed from any town of notable size, but it is the location that makes this place so special.

Within 100 miles of 45 million people and just over an hour drive from one of the largest metropolitan areas in the world, these waters, reasonably accessible from the densest population centers of our country, have drawn tourists and anglers for the past 150 years. They continue to do so today.

In the mid-19th and early 20th centuries, these rivers beckoned many early notables in the sport of fly fishing — anglers, presidents and celebrities alike. They came when our sport was young and the clear mountain streams were teeming with native brook trout. Inns and fishing clubs were built; houses turned into seasonal lodging to accommodate the many anglers flocking to “The Brodheads” as they were known back then.

When my granddaughter is her grandmothers age, there may be no trout for her to catch in these Pocono waters, and to me that’s a sobering thought. This historic trout fishery may well be remembered as an icon of a past era, a tale she tells her grandchildren as a memory of her youth.

“The Brodhead Creek is arguably one of the most historic sites in the development of American fly-fishing techniques and traditions,” Trout Unlimited member and author Don Baylor, wrote in his book The Brodhead: An Historic Trout Fishery. “Throughout the 19th and first half of the 20th centuries, virtually all notable anglers and angling writers visited the Brodhead, a stream that was instrumental in fostering the experimentation that advanced the art, sport and science of fly fishing for trout.”

These historic waters have faced their fair share of challenges from both man and nature. The late 1800s brought deforestation by the lumber industry, warming the waters and degrading the stream’s ecosystem with silt laden runoff. Brook trout populations waned and European brown trout were introduced. Then a devastating flood in the 1950s sent a wall of water barreling down from the headwaters into the Brodhead denuding it of the habitat necessary for stream life to survive and flourish. But it recovered from both, demonstrating its resiliency and once again becoming a world-class fishery.

“Recent biological studies attest to the exceptional water quality of the Brodhead watershed. Currently, 80 percent of Pennsylvania’s Exceptional Value streams — the commonwealth’s very best — are in the northeast corner,” Baylor wrote in his book. “In the Brodhead watershed, 13 tributary streams are classified, or are pending classification as Exceptional Value. Anglers from distant areas make pilgrimages to the Brodhead much as did those fly fishing pioneers in previous centuries.”

Bigger challenges face these waters today, ones that may appear more insidious but are just as threatening to the sustainability of this coldwater fishery.

Scientist tell us the impacts of climate change — warming waters, increased flooding, fire, and droughts — can lead to the loss of more than 50 percent of our coldwater fisheries by 2080, including the waters here in the Brodhead watershed. When my granddaughter is her grandmothers age, there may be no trout for her to catch in these Pocono waters, and to me that’s a sobering thought. This historic trout fishery may well be remembered as an icon of a past era, a tale she tells her grandchildren as a memory of her youth.

There’s a lot we can do to change this course and bring about a different outcome. Efforts to make our streams and rivers more resilient to the impacts of climate change is a good start. Local Trout Unlimited chapters are working hard to restore riparian buffers, carefully choosing tree species that are more tolerant of warming temperatures, conducting stream restoration projects to restore and strengthen aquatic ecosystems, and removing barriers that may impede aquatic organism passage into cooler headwaters.

But adaptation alone won’t be enough. TU’s continued support of programs and policies geared toward carbon reduction and climate change mitigation will be critical in keeping our coldwater fisheries of today, coldwater fisheries of tomorrow. Our practice of using sound science in decision making has made us among the most respected environmental organization in the nation – when TU speaks, decision makers listen. We’ll need to continue to flex our voices.

My 312 square-mile watershed with its plethora of coldwater streams is a special place to me, but we all have special places. Places to relax, reflect, think and pray … places to fish.

Hundreds, maybe thousands, of them scattered throughout our country and sometimes right in our backyards. Each place with a history all its own, telling a tale of anglers who came before, a history we contribute to today, a tomorrow we’d like to see continue. Places we’d like to safeguard and protect for future generations of anglers, places where we hope our grandchildren, when they are their grandparents age, can still experience the thrill of catching a wild trout.

Ann Foster is a board member for the Brodhead Chapter of Trout Unlimited in Pennsylvania. She also serves as a volunteer on Trout Unlimited’s Climate Change Working Group, part of the National Leadership Council.