Scientists often use models created by others to do conservation work, but sometimes they create new methods to obtain specific information for their needs. Trout Unlimited scientists recently collaborated with a group of outside scientists to estimate abundances for trout populations across the entire range of a threatened Lahontan cutthroat.

It’s safe to say no one thought the model created for trout would end up estimating human populations in remote areas of Africa.

“We always emphasized in our descriptions of our work that these weren’t just trout models,” said Helen Neville, Trout Unlimited’s Senior Scientist. They could also be used for estimating the populations of other species living in isolated populations. “At the time, we were thinking of organisms like pika – a small rabbit-like animal that lives in talus in the mountainous western United States – or sage grouse. Never did we imagine they would be used in Africa, to help with humanitarian planning.”

The modeling framework called Multiple Population Viability Analysis (MPVA) was a collaboration between Trout Unlimited and scientists from Georgia, Montana and Nevada universities, as well as the U.S. Geological Survey and the U.S. Forest Service. The work was funded primarily by NASA, with additional support from the Bureau of Land Management, Fish and Wildlife Service and Trout Unlimited.

Dr. Doug Leasure, then a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Georgia, was the primary modeler for the collaborative project. Leasure’s advisor at Georgia was Dr. Seth Wenger, formerly a postdoctoral researcher with the Trout Unlimited Science team in Boise. Wenger is currently an assistant professor at the Odum School of Ecology and the Director of Science for the River Basin Center at the University of Georgia. He has continued his collaboration with Trout Unlimited in his new roles.

The models use information from field collections of trout, captured over several decades by TU or state agencies and university partners during electrofishing surveys, paired with remote sensing and other data to estimate abundances for population across the entire range.

After his work with TU was completed Leasure landed a position as a research fellow working on the WorldPop GRID3 (Geo-Referenced Infrastructure and Demographic Data for Development) project — a research consortium at the University of Southampton in England.

Leasure realized the models he and the others had created for inland trout could be modified to estimate population densities throughout large regions of Africa. The real value is being able to provide reliable estimates even in areas where there is little data.

“I never imagined I would go from working on a threatened trout in the interior west to using the expertise I developed in that project to help with the types of things we’re doing in Africa, for people,” Leasure said from his office in England.

GRID3’s focus is to “generate, validate and use geospatial data on population, settlements, infrastructure, and subnational boundaries”. This information helps achieve sustainable development goals, providing a foundation for smarter infrastructure development, disaster relief planning, and deploying essential services like vaccine programs, across a region where censusing is limited and it can be difficult to estimate where to prioritize humanitarian resources.

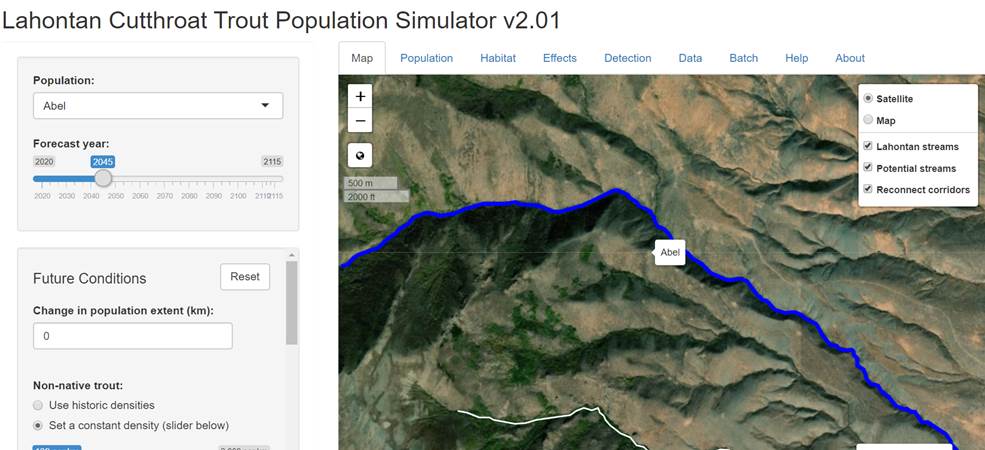

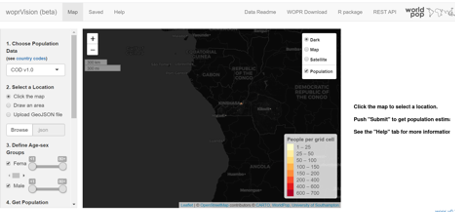

An important part of the collaborative work on trout was providing an interactive tool, the Lahontan Cutthroat Trout Population Simulator, which allows end-users to evaluate model results and even perform new simulations by changing certain influences on the model, like removing non-native trout or increasing stream temperatures. Now, inspired by this trout simulation tool, Leasure and his collaborators have built a similar interactive tool, the woprVision tool. This tool allows end-users to interact with population estimates in Nigeria, Zambia and five provinces in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and explore statistical uncertainty on a geographic map.

The trout work is also being recognized internationally elsewhere. The final paper from the project, focused on estimating extinction risks across all populations of the threatened Lahontan cutthroat trout, was published in the international journal Conservation Biology. In April it was chosen as the “Editor’s Pick” and was made accessible to the public for free.

“It is just awesome to see that this novel approach we developed with this broad group of scientists is being recognized for its usefulness in demographic modeling on the other side of the world, for such important needs,” Neville said. “This whole project has been the most inspiring collaboration I’ve ever worked on. It’s so fulfilling to see it continue to get traction in such surprising ways.”