From stream restoration to species recovery, science drives Trout Unlimited

Three of the greatest days of my professional career spanned from a Friday afternoon to a Monday morning.

On the Friday, Jack E. Williams, one of the pre-eminent aquatic scientists in the country and at the time the head of the fisheries program for the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), called and offered me a job as an entry level fisheries biologist.

Jack had, and has, a lot of science chops. In addition to becoming TU’s first senior scientist, he is one of the co-authors of the seminal Salmon at the Crossroads paper (American Fisheries Society, 1991) that documented the extent of the decline of Pacific salmon in the lower 48.

The three best days

I hung up the phone with Jack and jumped up and down. I then called my parents, brothers, and spent the weekend bragging to my roommates and my girlfriend. This was awesome. Fisheries biologists were cool dudes. Think Nick Nolte in Cannery Row.

Monday morning, Jack called back. “Chris?”

“Hey Jack.”

“Chris, the BLM personnel people called today, and said you never took a science course in college.”

Pause.

Jack: “Is that even possible?”

Silence on my end.

Hey, if the BLM was willing to hire me as a fisheries biologist without my having taken a science class, who was I to argue?

In the end, to the agency’s credit, I became a “policy analyst” instead.

The application of science to conservation

I still geek out on science, and I am an unabashed advocate of TU’s incredible scientists and their work. A few weeks ago, I joined TU staff in listening as our inimitable senior scientist, Helen Neville, and TU scientists from all over the country talked to us about the conservation implications of their work.

Helen kicked things off by describing the immense value of TU’s work in helping to recover the natural resilience of our rivers and streams to the sort of floods, fire, and drought that will only intensify through a changing climate.

One of TU’s top priorities is removing the four lower Snake River dams to recover wild salmon and steelhead in a region that, in a warmer future, is likely to contain most of the coldest stream habitats available to them in the lower 48). John McMillan, now the former science director of the TU Wild Steelhead Initiative, explained how hatcheries and hatchery fish can confound efforts to recover native salmon and steelhead.

Utah fisheries biologist Paul Burnett explained how he and his interns deployed temperature loggers (read: thermometers) to develop a new flow/temperature model to recommend instream flow recommendations that would be sufficient to sustain wild fish in the face of proposed new water withdrawals from a ski area in Utah. This type of work could readily be done by community scientists as well.

Erin Rodgers, a TU stream ecologist in New England, talked about how using restoration techniques that mimic natural processes helps to relieve and reduce flood pressure on infrastructure. Erin is working in western Massachusetts and pointed out, for example, how allowing a river to access its floodplain helps to reduce the potential flood damage to downstream communities and bridges and roads.

Matt Barney, TU’s senior programmer, and Jake Lemon, our Monitoring and Community Science manager, talked about their use of so-called EnviroDIY Monitoring Stations that imitate the work of United States Geological Survey (USGS) monitoring stations. The EnviroDIY Stations collect streamflow, turbidity, and other data the USGS collects, but at a fraction of the cost. A TU chapter, for example, can obtain Mayfly stations for approximately $1,500 and begin to better understand changes to their home rivers because of climate and development pressures.

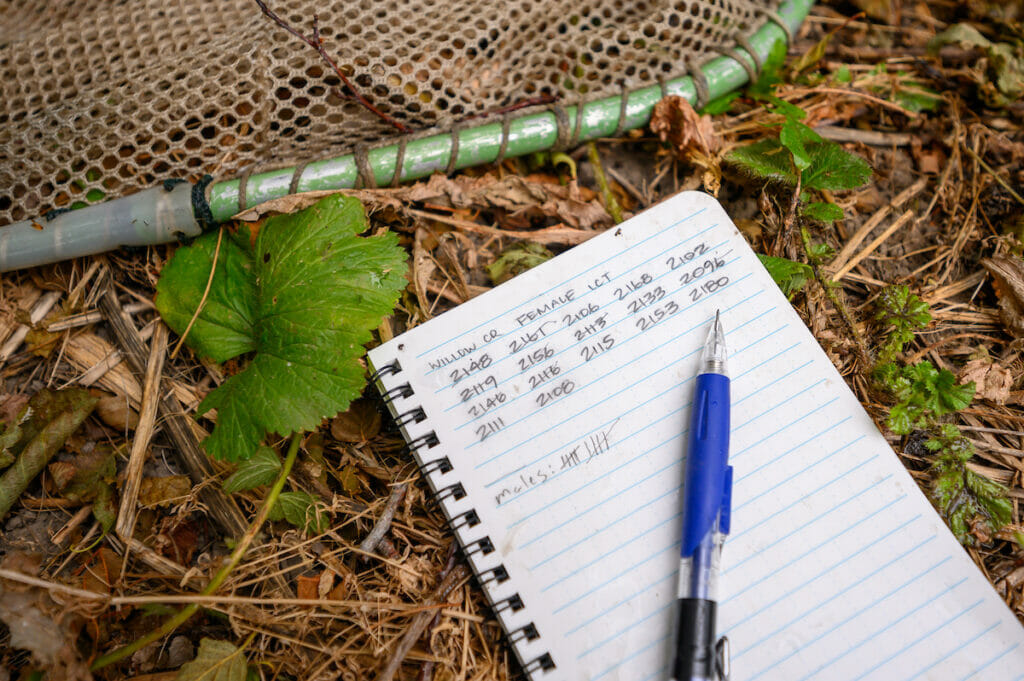

Keith Fritschie, the Upper Delaware River Restoration coordinator in my home state, the Great State of New Jersey, described how he trained and worked with 25 volunteers across 325 monitoring sites in the Garden State to standardize ways that community scientists collect data. This can improve our understanding of stream temperature and help cash-strapped state and federal agencies make better decisions.

There was still more. Tommy Cianciolo, a water quality project coordinator, discussed “low-tech, process-based restoration” in Oregon. Tommy and his partners are building the equivalent of beaver dams to help recover the role that beavers once played in restoring natural stream function, such as storing stream runoff in a watershed.

A few weeks later, Helen invited Caroline Nash, a hydrologist with C.K. Blueshift, to talk with us about the benefits (and potential limitations) of natural water storage to help make stressed watersheds more resilient. Nash affirmed TU’s basic approach but also helped us understand the complexities of this fast-emerging field.

Science driven

When I first began my career at TU, 20 years ago, we would talk about being science-based. Today, science drives how we set priorities.

Science drives how we advocate for the Clean Water Act.

Science drives our campaign to remove the four lower Snake dams to recover Pacific salmon.

Science undergirds our efforts to identify a shared agenda of caring for and recovering Priority Waters.

The thread that connects all the above is TU’s work to help communities and fisheries persist through a changing climate. Most of our science (and restoration) work is focused on recovering the basic purposes of a watershed: to catch, store, and then slowly release water over time. A healthy watershed is a sponge. Building beaver dam analogues, replanting riparian areas—these types of projects help protect communities and fisheries from the effects of flood, fire, and drought.

TU science drives results that help us to better care for and recover wild and native trout and salmon. I’m pleased to say that TU is no longer science-based. We are science driven.

Trout Unlimited supports the EPA’s new rule reinstating Clean Water Act protections for small streams and wetlands, and we can help push it across the finish line by showing a groundswell of support. Please take a moment to show how much you care about headwaters.