Most of us working on behalf of wild steelhead love our jobs. Still, after a long week we are ready to hit the water — and share some more steelhead knowledge.

This week we touch on a study conducted by Andrew Brown at the University of Washington, along with several co-authors. The paper can be found here.

This study focuses on the question of why hatchery salmon, trout and steelhead don’t survive as well as wild fish do in nature. More than 40 years of research on the subject has thus far not yielded a definite explanation.

Specifically, Brown et al wanted to know whether hatchery- and wild-reared juvenile steelhead developed morphological defects in lateral line structure, otolith composition and brain weight. Why? Results of research to date suggest that hatchery rearing significantly impairs the motor and sensory systems of fish.

The lateral line is a system of sense organs used to detect movement, vibration, and pressure gradients in the surrounding water. It runs along the side of the fish, from the back of the gill plate to the start of the tail. It is critical to fish in some of the same ways ears and hands are to humans.

Otoliths are small, bony, oval-shaped structures in the inner ear of the fish, and they are used to sense gravity and movement.

The brain is…well, we are going to assume we all understand more or less what the brain does for higher-order living organisms.

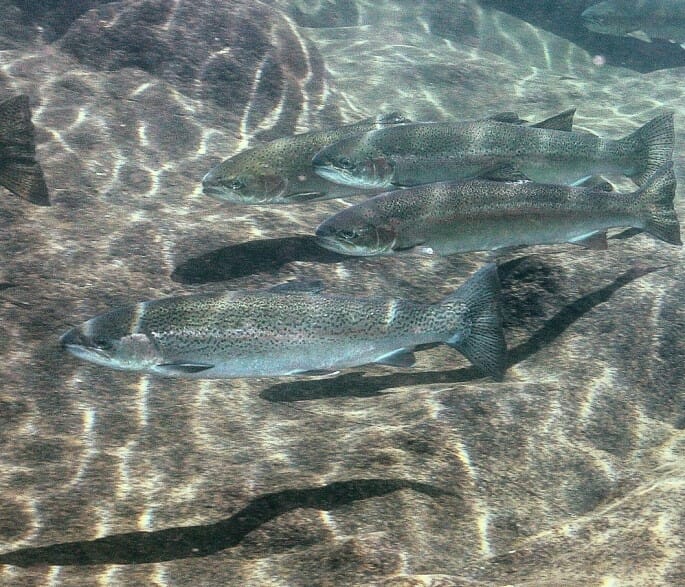

A post spawn hatchery female…with a little extra jewelry.

The rationale for the study in question is pretty straightforward. Hatcheries are known to alter important attributes in salmonids, which can result in hatchery fish displaying reduced swimming performance, predator avoidance, and altered migratory behaviors. While some research has been done on hatchery impacts on the motor and otolith-related systems of fish, less attention has been paid to the lateral line and its sensory system.

That is the goal of the Brown et al study: To determine if there were differences in the development of lateral lines, otoliths and brains in steelhead that were reared in a hatchery compared to wild steelhead that were not reared in a hatchery.

Here is what they found.

First, wild juveniles possessed significantly more superficial lateral line neuromasts than hatchery-reared juveniles. Neuromasts are sensory organs that form part of the lateral line system.

Second, wild juveniles also possessed primarily normal, aragonite-containing otoliths, while hatchery-reared juveniles possessed a high proportion of crystallized (vaterite) otoliths.

Aragonite is a carbonate mineral, one of the three most common naturally occurring crystal forms of calcium carbonate, CaCO3 (the other forms being the minerals calcite and vaterite). It is formed by biological and physical processes, including precipitation from the ocean and freshwater environments. This is important because otolith crystallization – deposition of lower-density vaterite in place of high-density aragonite – has been associated with reduced auditory sensitivity (i.e. poorer hearing) in hatchery-reared Chinook salmon.

Lastly, and consistent with the findings of other studies to date, wild juvenile steelhead had significantly larger brains than fish reared in a hatchery.

What does all this mean?

Well, these differences described in this study suggest hatchery-reared juveniles have reduced sensitivity to biologically important hydrodynamic and acoustic signals from predators and food sources. It may also reduce their ability to sense physical non-biological factors, such as flow and current speed.

Further, the results also suggest there is possible atrophy of brain areas associated with processing sensory information (i.e. lateral line systems) in hatchery fish.

This study did not look into the reason these changes occurred nor whether it impacted their survival and ultimately, their reproductive success. Nonetheless, this seems like an important difference between fish that is likely created by the very different rearing environments.

These results may have meaning in the real world, especially for anglers — if you want a fish to sense and be able to evade a sea lion, the lateral line, otoliths and brain size in wild fish may give them a distinct advantage over hatchery fish. Further research on this topic could provide more insight into how these differences influence survival of wild and hatchery steelhead.

As we have discussed numerous times in this and other forums, Wild Steelheaders United and Trout Unlimited are not opposed in principle or practice to hatcheries, except in waters which have the habitat quality and wild fish stocks to be managed as wild fisheries.

We believe hatcheries continue to play an important role in steelhead fisheries management, especially in watersheds with degraded habitat values. But virtually all research to date, including the Brown study referenced here, indicates that wild steelhead are cheaper to produce, survive better, and fight better at the end of an angler’s line than hatchery fish, and we should prioritize management of rivers for wild stocks whenever possible.

That’s why we are promoting what we call the Portfolio Approach to steelhead management: hatchery supplementation in watersheds where this is necessary to provide angling opportunity, and, in watersheds where habitat quality is high and wild stocks are abundant, diverse, and provide angling opportunity, we should not stock hatchery fish.

Wild steelhead conservation, and provision of sustainable steelhead fisheries, are not mutually exclusive if we are careful to prevent hatchery steelhead from degrading wild populations. The Portfolio Approach achieves a workable balance between these two big-picture goals — especially if we want the next generation of anglers to have the opportunity to fish for wild steelhead, and to do their part to keep alive that distinctive heritage.

John McMillan is the science director for TU’s Wild Steelhead Initiative and an accomplished author and steelhead angler. This article was originally posted on the Wild Steelheaders United blog.