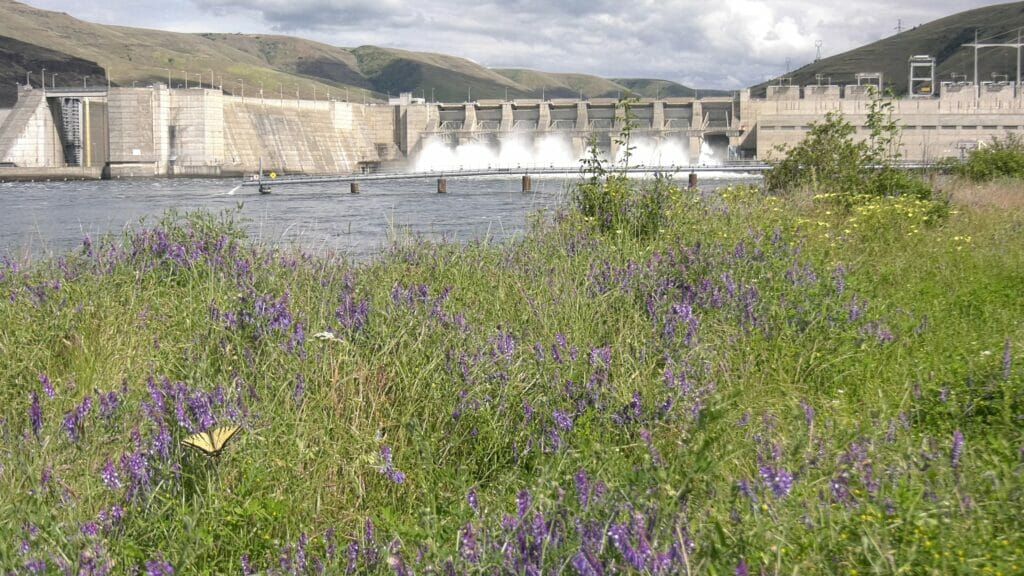

Salmon in the Snake River Basin must navigate eight major dams between the Pacific Ocean and Idaho.

Four on the Columbia River and four on the Snake. Removal of the four Snake River dams could help quickly declining wild salmon populations recover, which is why there is significant momentum behind the growing effort to remove those dams.

But all eight are worth recognizing because they mark a significant turning point in America. The chain of eight represents our decision to turn away from the wild so we could turn on our lights.

When you visit a dam, look at it, then look up. Power lines web high over the water. At the conversion of man and Mother Nature, there’s a massive amount of energy. That energy turns into hydropower used by public utilities in the Northwest.

The watts that keep our world rotating are cheap, but they are not free. Nearly 30 percent of ratepayers in the Northwest light up their life with power provided by Bonneville Power Administration. BPA designates a portion of every power bill for its source water and the wildlife living in that water. We’ve spent more than $18 billion on salmon and steelhead recovery in the last 30 years, since about the time Snake River sockeye salmon were protected under the Endangered Species Act. Those billions come from our wallets every time we flip a switch and those billions haven’t brought salmon back.

I live in Idaho Falls, Idaho. My house is warm, my fridge is cool, my computer works, and my porch is lit. Those things happen because I pay my power bill. I’m an Idaho Falls Power customer, a city-owned utility that’s part of BPA’s grid. Thirteen cents of every dollar I pay goes to fish and wildlife recovery efforts funded by BPA—but really, it’s funded by you and me.

In one month, my household of four uses 617 kilowatts, costing $39 total with $5 of that allocated to salmon recovery. Multiplied by 12 months for 20 years, and I’ve paid $1,200 to help save fish trying to navigate these aging dams. I’ve paid it, and you’ve paid it.

When we pay for hydropower, we’re paying for flow. Flowing water spins undersurface machines, or turbines. That spinning action creates electricity sent to power lines originating at dam sites. Those lines tentacle across the country lightning fast, like veins pumping blood, so that when you turn on your screen, there’s instant image. That’s hydropower. Throwing water directly on a socket is a terrible idea, but when it pushes through a series of engineering wonders it’s light-bulb brilliant. That’s why Columbia River Basin is a workhorse—a workhorse that’s wreaking havoc on fish. So why not try something we haven’t tried before?

There are dam removal proposals coming out of Idaho, Oregon and Washington that show the Northwest can have its power, and its farms, and have fish too. Our only loss would be those four walls in the water. Without those walls, the workhorse goes back to serving its original master.

The river used to work for fish. Now it works for us. Think about that the next time you leave the lights on.

This blog was written and edited in June 2022.

Outdoor journalist Kris Millgate is based in Idaho where she runs trail and chases trout. She followed salmon migration solo during the pandemic for the Emmy-nominated film Ocean to Idaho. Her new film, On Grizzly Ground, premieres in August with her third book My Place Among Beasts. The statistics in this story come from her second book My Place Among Fish. See her work at www.tightlinemedia.com.

Fact box:

| Watts within Water for Household of 4 | |

| Monthly cost for fish & wildlife recovery: | $0.13 per dollar |

| Monthly power use | 617 kilowatts |

| Monthly power bill | $39 per month (includes $5 for salmon) |

| $5 x 12 months x 20 years = | $1,200 for salmon recovery |

Source: Idaho Falls Power and author’s utility bill 2022