Would you recognize a native interior redband trout if you caught one?

Editor’s note: Daniel Ritz is fishing across the Western United States this summer in an attempt to accomplish the Master Caster class of the Western Native Trout Challenge. He will attempt to land each of the 20 native trout species in their historical ranges of the 12 states in the West. You can follow Ritz as he travels across the West by following Trout Unlimited, Orvis, Western Native Trout Challenge and Montana Fly Company on social media using the #WesternTroutChallenge.

Our Western Trout Challenge series was purposefully written in the first-person. Choosing to write from my subjective voice was done purposefully in order to hopefully create a sense of relatability. Articulating the experience is the priority and I consider myself only a vessel as compared to a protagonist.

That said, I have introduced myself only when necessary and largely by negative definition. By negative, I don’t necessarily mean self-conscious or self-loathing, but, instead that I have revealed my character by telling you what I am not more so than by giving you characteristics to build a profile from.

What do you know? I am not a biologist. I am not a geneticist. I am not a professional fisherman or a guide. I am not an expert caster. I am not an influencer. I am not a master fly or knot tier and it is precisely not being all of these things (and more) that allowed me an amazing moment of discovery and connection with a core native species that is very often only identified, like myself, by what it is not.

After pursuing the native species of the Kern River plateau in the cauldron that was southern California, I spent a few days underneath the high, clear skies of Lake Tahoe. After observing the emergence of the Tamarack Fire in nearby Markleeville, I was relieved to disappear into the dense, lush forests of central Oregon.

As you pass Bend, Ore., the forests grow denser, the dirt roads that appear as tributaries to the few paved thoroughfares become more brick colored. As Black Butte — an impressive extinct stratovolcano in the Deschutes National Forest — rose before me while approaching my turnoff to Camp Sherman, I stopped to take a picture and noticed my shoes and pants were wet with residual moisture clinging to the junipers.

It had been weeks since I had seen a drop of rain.

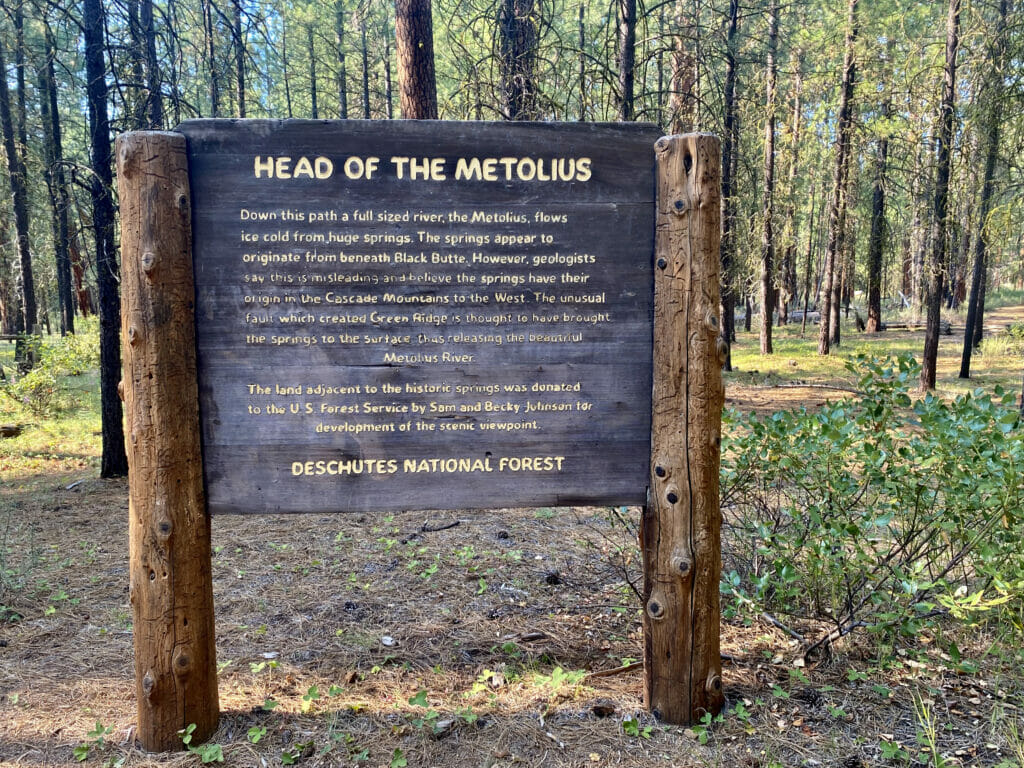

Just below Black Butte — a giant spring creek — the Metolius River literally emerges from the earth a full-sized river. In areas where heavy flows have created deep underwater channels the water appears almost turquoise in color. The dark earth, largely shaded from direct sunlight from the abundant lodgepole pines, clashes with the vibrant blue hues of the emerging water.

Named a wild and scenic river in 1988, a 2015 water-quality study commissioned by the Friends of the Metolius found the entire length of the river to be “above drinking water quality” surpassed only by a small stream in the remote Blue Mountains region. This exquisitely clean and uninterrupted stretch of river is known for supporting one of the healthiest populations of the federally endangered bull trout and is one of the only rivers in the country where they can be legally targeted by anglers. The Metolius Basin is also ground zero for an exhaustive wild Chinook, sockeye and steelhead recovery effort.

I share all that not simply to expose the Metolius — it is already a well-known fishing destination — instead to show where my attention was focused. Truth be told, this was supposed to be an extra stop for me. Just for fun. Sure, I had a chance of hooking a bull trout, but really, I was a few days ahead of schedule after being smoked out of northern California and wanted to spend some time experiencing the Metolius, often mentioned in the discussion of the most beautiful rivers in America.

I was excited, but relaxed as I pulled up to try my hand at what the Native Fish Society called the “crown jewel of the upper Deschutes Basin and a place of exemplary ecological value in the state of Oregon.”

As my eyes darted up and down the river, I realized I was a bit overwhelmed by the abundant options. I decided to take the advice of a friend I had met up with the night before in Klamath Falls and work my way down from Wizard Falls Fish Hatchery.

As good a place to start as any.

As the sun set, I worked pool after pool with no luck, switching flies a number of times in an attempt to match the few bugs I saw hatching off the water. Flustered, I re-rigged and decided to switch tactics. I was here to enjoy myself anyway, right? Why not fish how I wanted?

Tying on a large sculpin imitation streamer, I began swinging from the deep center channel of the river to in front of and behind its plentiful log jams. Maybe if I wasn’t lucky enough to catch a lot of fish, I would be lucky enough to encounter one of the Metolius famed bull trout, known for violent strikes on baitfish imitations.

Only a few casts later, I almost had the stout 7-weight ripped from my hands as the line went stiff at the end of a dead swing. A few vicious shakes and multiple runs forced me to scurry down the river in order not to lose what felt like a solid fish. Awkwardly perched on a riverside rock above a deep hole, I finally was able to bring the maybe 18-inch fish to the net and realized my footing wasn’t the only thing I wasn’t sure of.

I didn’t know what kind of fish this was?

This summer, I have consistently been acutely aware of the species of my pursuit. This fish… this fish didn’t quite fit in any molds that I knew of.

The most striking feature was its vibrant bright red band, a phonetic trait I closely associated with species of rainbow trout. But, its coloring was different in a way that I still struggle to articulate. More vibrant. Dark spots were more defined but less plentiful than other rainbows I have encountered. It glowed a soft golden color, somehow unlike the reflective scales of the coastal rainbow. Also, its adipose fin was fully intact. Was this just a wild rainbow?

After snapping a few photos from my rock perch, I found myself obsessing over finding out what this fish was. The next morning, I made the quick drive back up to the hatchery where I had a bit more service and could put out some feelers and confirm what this beautiful trout was.

I have toured a few hatchery operations in my day, but Wizard Falls Fish Hatchery absolutely takes the cake as an interpretive ambassador for fish production. A person of less conviction regarding wild species could be wooed by the informative signage, open operational buildings, friendly staff, and plentiful runs loaded with fish chomping at the bit for the next toddler to chuck a handful of pellets.

Suddenly my phone pinged in my pocket and I anxiously pulled it out to receive my verdict.

“That’s a redband, far as I can tell,” read a text from Trout Unlimited colleague, Western Native Trout Initiative (WNTI) volunteer and all-around native species guru Tyler Coleman. “I wouldn’t question it if someone submitted it.”

That was great news because Coleman is the guy that receives and evaluates all WNTI submissions.

A redband trout! I hadn’t even considered it. Somehow, I had been so focused on figuring out what hybrid of rainbow trout that I had not even thought of the redband. Without even knowing it, I had hooked into yet another of the Western Native Trout Challenge’s recognized species.

Turns out that while the Wizard Falls Fish Hatchery lies directly on the banks of the Metolius, stocking ceased in the early 1990s to allow wild fish to regain a stronghold. All fish in the Metolius are wild and all rainbow sub-species are native redband trout.

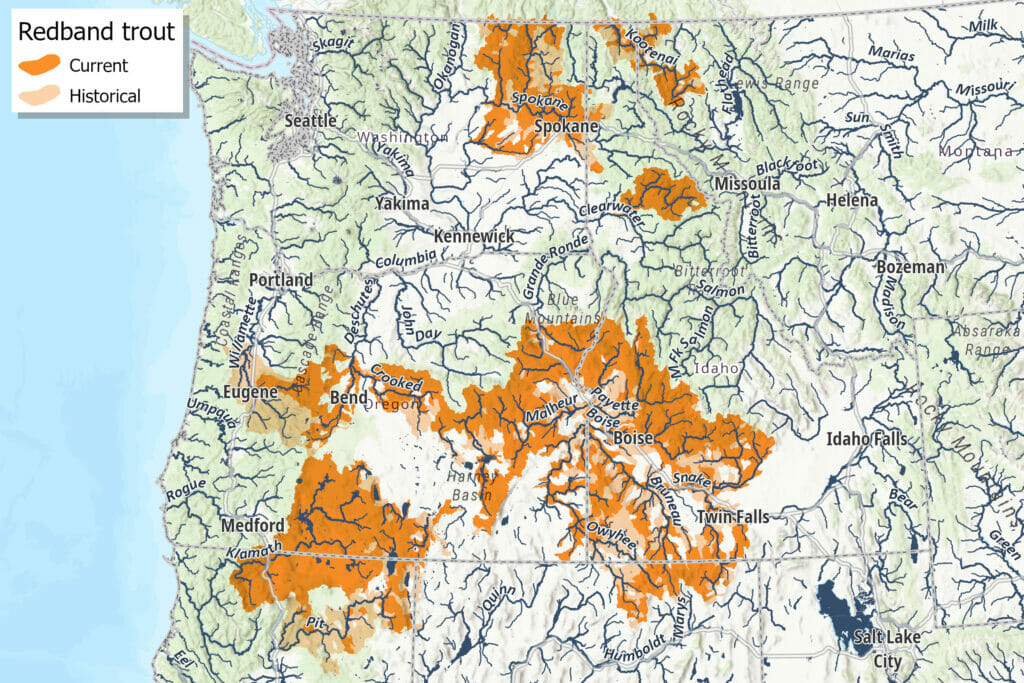

Interior redband trout historically occupied portions of major river basins that were considered outside the range of anadromy in six states—Nevada, California, Oregon, Washington, Idaho and Montana. The Columbia River redband trout is found in Montana, Oregon, Washington, and Idaho, and the Great Basin redband trout is found in southeastern Oregon and parts of California and Nevada.

On the third morning of camping along the banks of the Metolius a dense smoke moved in from a nearby wildfire and I was ushered east across the central Oregon badlands toward Idaho.

Before heading home, I decided to make a pit-stop stop along the mighty Salmon River outside Riggins, Idaho, to spend some higher quality and more intentional time with redband in my home state.

After crossing a pack bridge into the Gospel Hump Wilderness, I worked the pockets of a boulder-riddled high-gradient beautiful stream loaded with Columbia Basin redband. These fish showed more of the “classic” redband characteristics I was familiar with. Well defined par marks that last well into adulthood as well being on average 6-10 inches at best. For hours I scrambled, climbed and swam upstream connecting with beautiful, eager native redbands on almost every cast.

It was the stuff of angling dreams yet, until a few short days prior, I wouldn’t have even confidently been able to identify a native interior redband in an underwater lineup. As I reached the highest point on the stream that I was comfortable climbing, my sandaled feet bloodied and blistered, I pondered what a shame that was.

Here I was, Trout Unlimited’s certified “trout enthusiast” attempting to become recognized as a “Master Caster,” and it was only a few days prior that I was able to confidently identify this species native to my home region by what it was instead of what it wasn’t.

Back home in Boise I was scanning Facebook when I saw a man ask an Idaho-based fishing group for help identifying a fish he had caught. From where he claimed to be fishing and from the looks of the photo it was a beautiful Columbia Basin redband trout.

“Is this just a rainbow trout?” the man asked.

We see it all the time, someone on social media asking, “Can someone help me identify this fish? It is usually met with a shockingly basic mix of smart-ass people poking fun, followed by educated anglers offering kind educational answers and lastly, unfortunately, a number of people offering objectively incorrect answers.

In between the smattering of “IOt’s a catfish” and “That’s a hatchery rainbow” responses, I confidently typed, “Columbia Basin redband trout. A native species.”

In a way, redband trout appear to have been lost in time, lumped into the ever expanding and complex umbrella of “rainbow trout.”

As I considered my experience with and my personal parallels to the often negatively defined interior redband trout, I saw a few more comments come in on the post about species identification.

‘It’s a shark,” someone wrote.

If you are a resident of one of the states mentioned above, be sure to familiarize yourself with the native redbands of your watersheds. Mistaken identity is exactly that: a mistake.

Identity theft is a crime.