A high alpine meadow in New Mexico. Daniel A. Ritz photo.

How community is key in Rio Grande cutthroat conservation in New Mexico

Daniel Ritz is fishing across the Western United States this summer in an attempt to reach the Master Caster class of the Western Native Trout Challenge, attempting to land each of the 20 native trout species in their historical ranges of the 12 states in the West. You can follow Ritz as he travels across the West by following Trout Unlimited, Orvis, Western Native Trout Challenge and Montana Fly Company on social media using the #WesternTroutChallenge.

My family loves to remind me that as a child I wouldn’t be able to sleep the night before Christmas Eve and would wind up exhausted and emotionally drained in the early morning before collapsing due to anticipation of Santa coming.

My mother and other loved ones still love to poke fun at my eagerness, often reflecting on how this foreshadowed my passionate and easily excitable personality.

After arriving in New Mexico — one of my favorite places on earth — I couldn’t help but feel that same sense of excitement for my first experience with Rio Grande cutthroat trout high in the Carson National Forest. I had been looking forward to it for so long.

True to form, I was barely able to sleep on my first night in New Mexico after receiving an alarming text from Trout Unlimited’s New Mexico Water and Habitat Program Manager Toner Mitchell, whom I was to meet the next day.

“Comanche Creek’s going to be tough,” Mitchell told me when I shared my initial plans. “I’m worried about the heat and low populations.”

Admittedly perturbed, I decided it was best to take Mitchell’s suggestion and adjusted course to another river, a tributary of the Pueblo Rio east of Taos. In fact, Mitchell said this stream was the first place he had ever caught a trout. The personal connection to this tributary of the Rio Pueblo immediately refueled my enthusiasm.

After climbing thousands of feet into the Carson National Forest, all seemed to be going according to plan. I was able to identify a feeding trout only partially hidden beneath an undercut bank. After performing a half-way decent cast along the bank just upstream of the feeding fish, I watched as it adjusted from its resting lane and devoured my floating Adams.

Bringing the fish to the net, I was dismayed to see that it was in fact a beautiful wild, but invasive, brown trout.

“Shit!” Mitchell said early the next morning when I met him, his disappointment visual and obvious. “That’s not good.”

I first met Mitchell during my excursion into the Gila and his focus was obvious from the very beginning. Mitchell’s commitment to and engagement with the native Rio Grande’s is obvious, but maybe not focused in the way you may expect.

“The community is the most important part of any native cutthroat project,” Mitchell told me in an interview preparing for my time in New Mexico. “Community is at the focus of every project we take on here. There are maybe three generations of people that don’t relate to the reality that Rio Grande cutthroat trout being the only fish in these waters. But you can’t just come in and think that telling folks what they should do, what the ‘trout guy’ thinks they should do, is going to be good for anyone. (New Mexico) is probably different from any other place you’ve been so far. I try to start with ‘how can I help?'”

Here, Mitchell touches on a common anecdote in the conservation world. I paraphrase when I repeat the words of conservation elders noting that you spend more time working on people than wildlife or habitat in a successful conservation project.

In northern New Mexico, Mitchell and others know that the future of the Rio Grande cutthroat trout and other native species is dependent on true collaboration with local communities.

“New Mexicans have been here on this land for more than 400 years,” Mitchell said. “You can’t come in with a ‘trout guy’ perspective. These are age-old relationships that we have to foster and work together with to build trust.”

What Mitchell speaks of is the increasingly rare genuine win-win situation. This is rare as it isn’t at all equivalent to “settling” or general “compromise” where everyone gets something, but no one gets what they want, but instead, scenarios where native trout and local communities can cohesively prosper on the land in perpetuity.

As Mitchell and I began what for all intents and purposes could be called bushwhacking through dense brush and fallen trees along a stream in the Carson National Forest, he told me the debris was from a once-a-century flood in the late 2000s.

“This fallen debris gets us closer to what folks sometimes call a Stage Zero Condition,” Mitchell shared. “These fallen trees restore the banks and continue to divert the river to form braids that enrich the surrounding soils and riparian area. It looks like a mess, but, this is beautiful.”

As I ducked under another fallen pine, I wondered if I wasn’t just bad luck. After our excursion along Willow Creek in Gila trout country, I think Mitchell was beginning to wonder if we were just destined to have difficult fishing conditions together.

Thankfully, this creek was, in fact, chock full of eager, beautiful Rio Grande cutthroat trout. I watched as Mitchell carefully placed bow-and-arrow casts to fish in log jams before jumping upstream and connecting with native trout in pronounced runs.

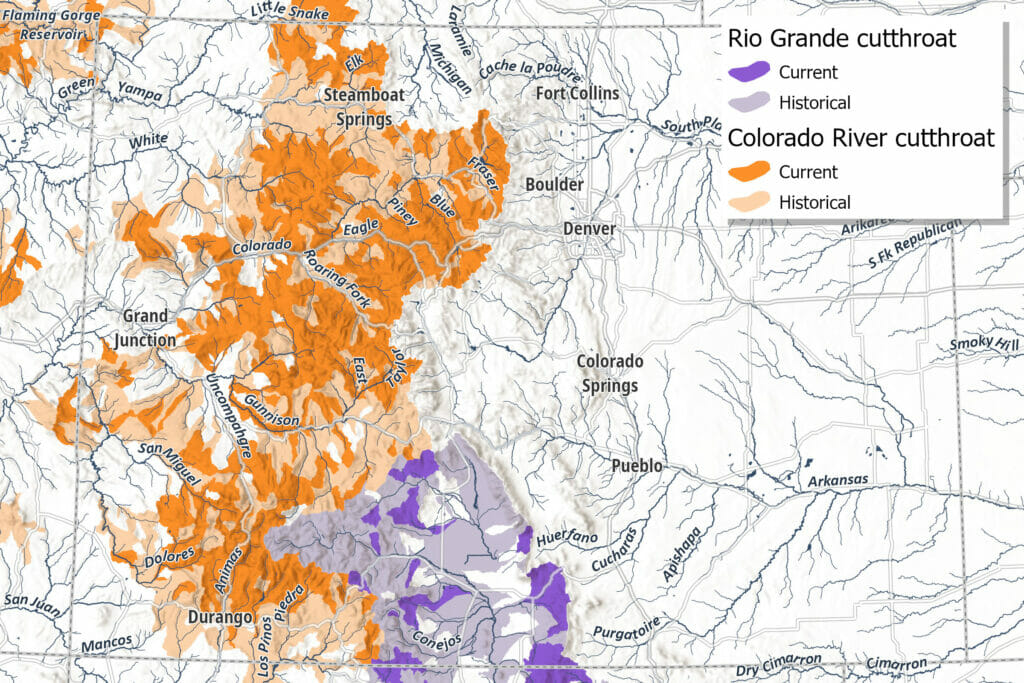

Compared to their Colorado River cutthroat trout neighbors, Rio Grande cutthroats appeared to have a more orange color to them and seemed generally lighter in complexion. Perfectly blending into the high-altitude streams, their eruption from cover to take dry flies was often a surprising explosion of color.

“The story of the Rio Grande cutthroat trout is metaphorical to these rural communities,” Mitchell said, noting that he acknowledges the dense history of New Mexican culture, and embraces the diverse multiple use history of the land.

“It isn’t a matter of me asking ‘How do we help cutthroat back to your streams?’ It’s acknowledging how we can keep more water in the streams, how we can help cattle and crops while enabling cutthroat habitat,” Mitchell said.

In a world of retroactive compassion, Mitchell and his staff’s active community inclusion and comprehensive focus was refreshing.

I regularly tell people that I love New Mexico because of the complex and dynamic culture.

Ironically, in some of the oldest continuous communities in the United States, history isn’t something that happened, it’s actively happening and as I like to say, “In New Mexico people don’t look over their shoulders in the past, they wear it on their shoulders.”

“I hope folks recognize the Rio Grande cutthroat trout as an icon of their culture,” Mitchell said, making the point that it’s colorful appearance and breathtaking gill plates literally embody elements of the Zia, the symbol on New Mexico’s flag.

As thunder loomed, Mitchell and I wrapped up our brush ridden fishing day. Before heading to the truck, we decided to fish below the artificial barrier, created with the help of funding from the Western Native Trout Initiative to see what we would find.

It wasn’t but a few casts later we had beautiful Rio Grande cutthroat on the line.

Within sight of the artificial barrier, I realized our end-of-the-day experiment below the barrier spoke directly to my experience of Rio Grande cutthroats.

In New Mexico, Rio Grande cutthroat trout are, but shouldn’t be, on the fringe. Sure, I had initially gone to a fishery described as purely cutthroat and found it infiltrated by non-native species, but, at the end of the day, we ventured below what had artificially been created as a safe space and found that the native, original species was alive and well.

During my time in New Mexico, many of my experiences weren’t at all like I anticipated, but as I drove away toward the Pacific Coast in preparation to try and catch the native trout of California, I found myself emboldened that at least Rio Grande cutthroat aren’t something that is behind us.

The future of Rio Grande cutthroat trout, like the culture of New Mexico, is evolving right in front of our eyes, not over our shoulders. Will we be able to listen to each other, to evolve together, as opposed to instructing and directing?

It seems to be the only way.