One can make the case that the Catskills of New York are the cradle of American fly fishing.

Montana, with the “rivers that run through it,” may be the sport’s spiritual home.

But unequivocally, my home state of Oregon is the birthplace of the McKenzie River drift boat—known more colloquially as the drift boat; or “Drifty” (the name of my neighbor’s Koffler craft); or the “H.M.S. Thin Mint” (an amalgam of the surnames of my fellow boat owners Helms and Moskowitz, and an allusion to the boat’s color scheme).

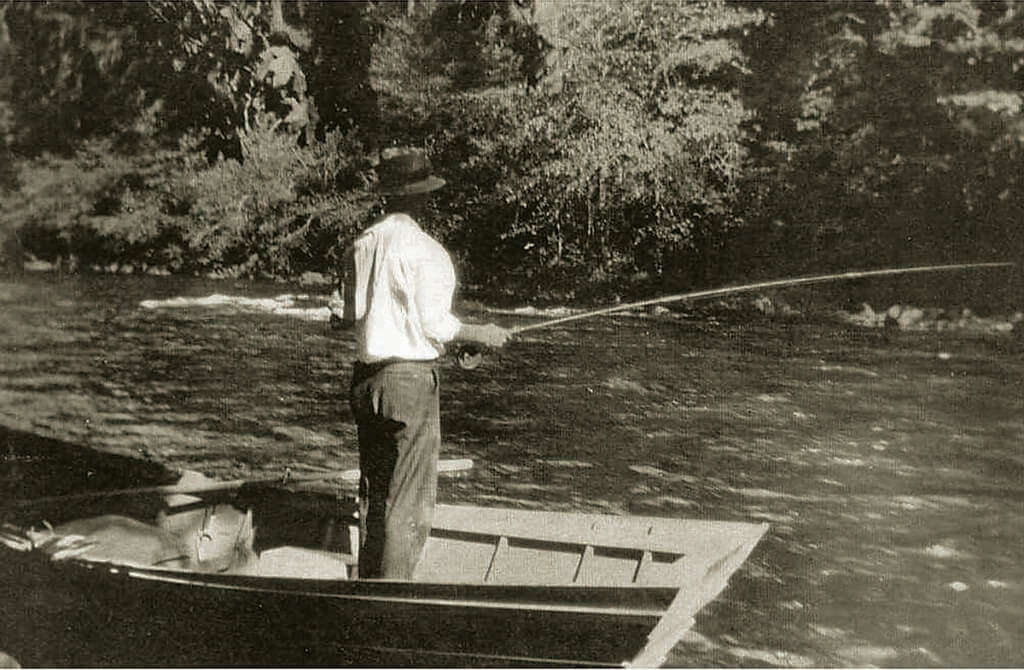

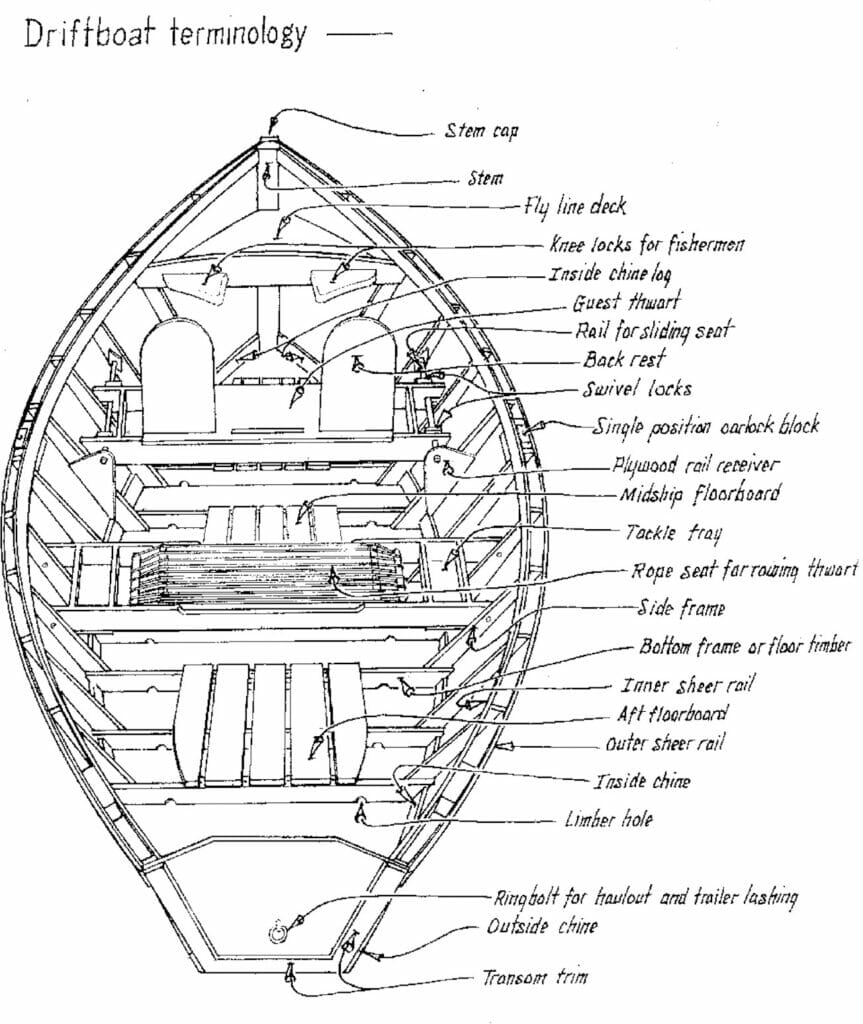

What, exactly, are the features that distinguish a McKenzie River drift boat? I asked fellow Oregonian Roger Fletcher, a drift boat aficionado and author of Drift Boats & River Dories: Their History, Design, Construction, and Use (Stackpole Books). “From a design perspective, the boat’s uniqueness is its flat bottom side from chine to chine, the continuous rocker fore to aft, and the straight and usually flared sides,” he shared. “These are the elements that give the boat its maneuverability and make it the whitewater fishing platform it was shaped to be.”

Below, thanks in large part to Fletcher’s meticulous research and genial nature, is the short story of how Western trout anglers’ most relied-upon watercraft came to be. (It should be noted that at nearly the same time, a slightly different boat design was taking shape on the Rogue River, 150 miles or so to the south. Perhaps that will be the topic of a future story, but we’re not focused on that here.)

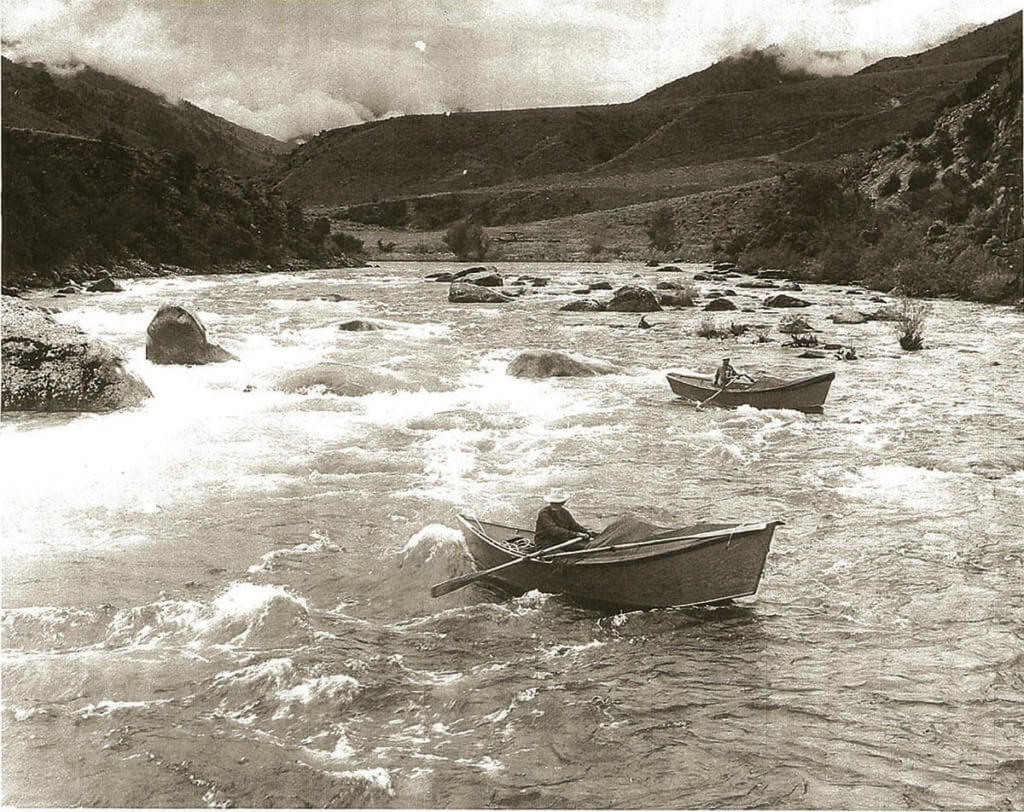

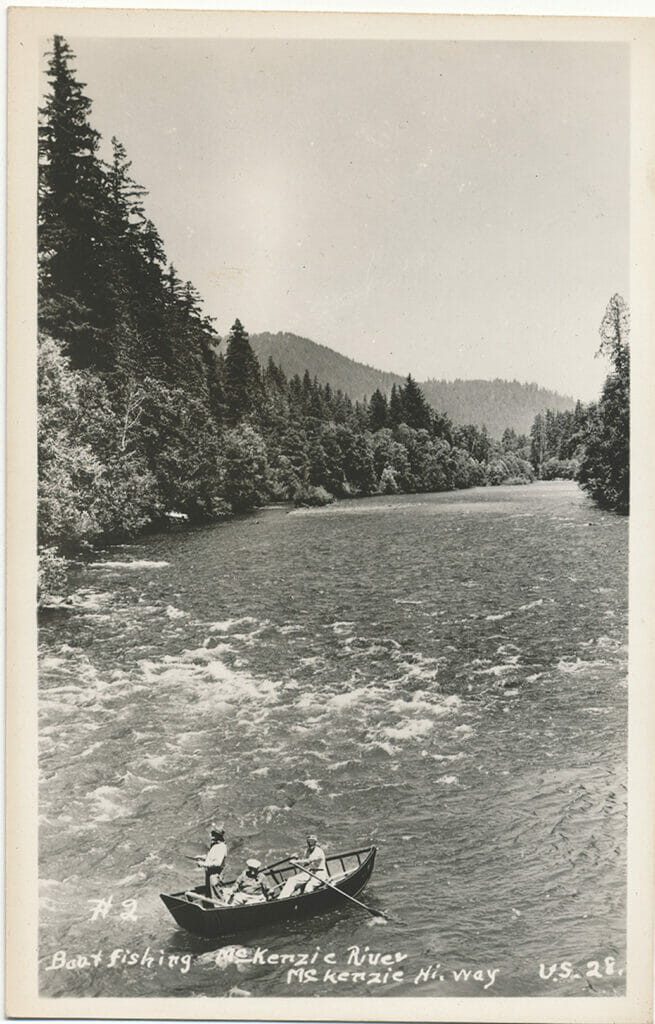

The McKenzie River flows some 90 miles from the Cascades in the east to its confluence with the Willamette River in the west, just north of the city of Eugene. Largely spring fed, the McKenzie runs cold and steady throughout the year. Today, the river has been tamed a good deal by three dams on its mainstem (and three others on its tributaries). But a trip to the upper section of the river will give you a sense of its former wildness, where mammoth boulders and shelves of basalt create class III and IV rapids, but also excellent holds for healthy wild redside rainbows. Though settlers of European ancestry had begun flowing into the Willamette Valley via the Oregon Trail only a generation before, by the 1870s, there was enough of a population—and enough prosperity—to bring visitors to the McKenzie to bathe in adjacent hot springs and fish. With the construction of paved roads leading up the river and the advent of the automobile, more anglers came. Many wanted someone to row them about on the river, and a market for guides was created. (According to the McKenzie History Highway Project, the first person on record to guide anglers on the McKenzie was Carey Thomson, who started out rowing for friends. This was circa 1909.)

The craft available at the time were basically rowboats, 18 to 22 feet in length, 3 feet wide, with a freeboard (the distance between the waterline and the gunwale) of about 14 inches. They were fabricated from planks of locally available wood, including Douglas fir and cedar… which is to say, they were not particularly light. Though the early McKenzie guides understood the advantages of rowing against the current and the need to maneuver laterally to avoid obstacles, achieving these goals with the “old scows” was at best a challenge. In his book, Fletcher quotes John West, a young guide on the McKenzie, speaking to the inefficiencies of the boat du jour: “You’d pull your arms off and not accomplish much…” and, “you went through the rapids with one oar in the water and a bailing can in the other.” In 1920, West and his brother Roy decided they could improve upon the current rowboat design and built a boat with a bottom of less than 16 feet in length. Though the Wests’ design lacked most of the features we associate with a McKenzie boat, it was the first craft customized for the river, and was quickly adopted by many regulars. A few years later, a local angler named Veltie Pruitt made an even smaller boat that was also lighter. It caught the attention of a prominent guide, Prince Helfrich. After Helfrich hired Pruit to build a boat for him, this style gained popularity on the river. (Three generations of the Helfrich family have guided the McKenzie and other western rivers, and continue to do so today.)

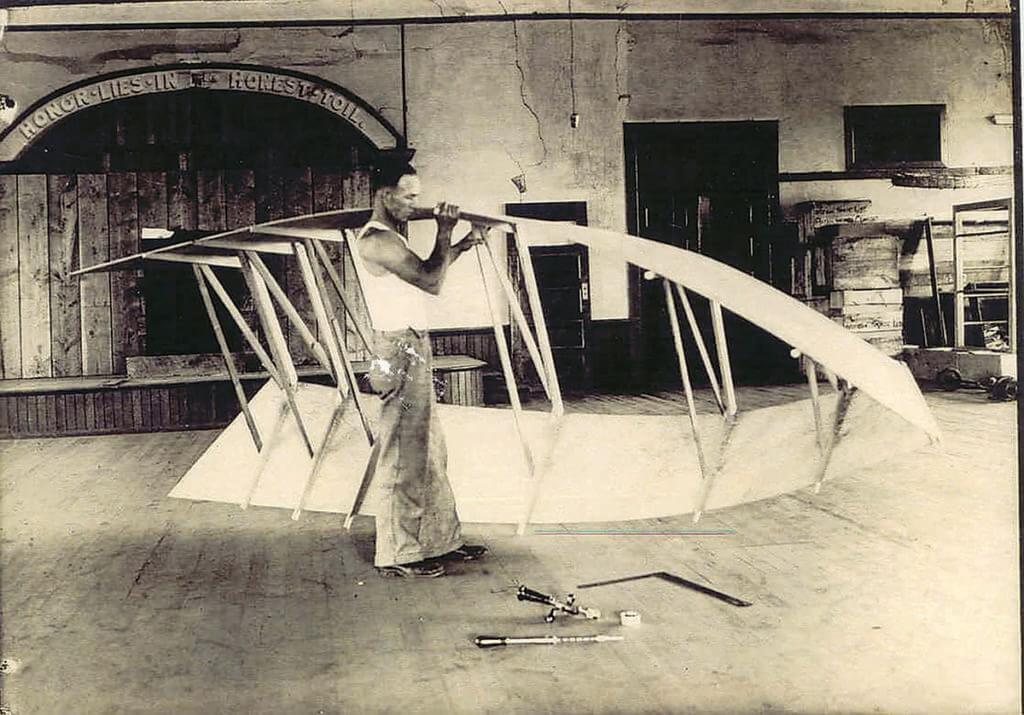

The next noteworthy development for McKenzie River drift boats was not so much a design alteration as change in materials and engineering. It evolved from the woodshop of one Torkle “Tom” Kaarhus, a Norwegian immigrant, circa 1936. Roger Fletcher points out that up until this time, boats on the McKenzie were built with board and batten construction—“with spruce ribs, cedar planking, oak chines and bottom battens.” Kaarhus recognized that plywood could greatly simplify boat manufacturing. Side panels could be cut from a single sheet; frames could be pre-formed. Plywood, both flexible and durable, was easy to work with, made even lighter with cedar and spruce frames, versus heavier Douglas fir and white oak. Kaarhus applied his new construction methods to what was essentially the West brothers’ design, and he usually referred to his creations as “West boats.”

“Kaarhus did a number of practical tests with the new material,” Fletcher added. “Once he was satisfied with its integrity, he moved from planked boats to plywood skins. The material was light, flexible and it gave rise to free form construction. Jigs or strong-backs would soon be requirements of the past. Kaarhus also innovated the development of drift boat kits which allowed guides and others to build their own working boats.”

In the early 1940s, Woodie Hindman brought anglers another great leap forward in drift boat design. His boat-building career had begun under the tutelage of Tom Kaarhus in 1935, and by 1941, he’d started his own shop in Springfield, Oregon. Hindman’s contribution came in the form of the first double-ended drift boat, inspired at least in part by a float he did with his wife on the Idaho’s Middle Fork of the Salmon in 1939.

Up until this point, all McKenzie boats had been square-ended. As Fletcher notes, Hindman “simply repeated the bow frame pattern and replicated it for the stern, except that he lengthened the downriver frames to accentuate the downriver prow.” Soon, Hindman’s double ender came to be the McKenzie River standard. On his website, “River’s Touch,” Fletcher describes the joys of the double ender design: “It was a charm to row due to the accentuated rocker. It would pivot on a dime. This boat sports the most extreme rocker of the early McKenzies. Its crescent lines are lovely. As Woodie noted in one of his diaries, the lines had a purpose: “…to resemble the crescent shapes of the waves.”” In Fletcher’s opinion this change, along with Kaarhus’s use of plywood, were the two most significant developments in drift boat design and construction.

It should be noted that the drift boat shape we know today was adopted in 1948, when Hindman replaced the up-river bow with a small square (or “tombstone style”) transom. It’s believed that this change occurred after a friend of Hindman’s, Everett Spaulding, requested the transom to accommodate a small motor so he could push through slower water on the lower reaches of the Rogue and Siuslaw Rivers.

Of course, there have been many developments since. Aluminum boats (credited to Willie Illingworth) came online in the ‘70s. LaMoyne Hyde introduced the fiberglass drift boat in the early 1990s. Both served to democratize drift boats to an extent: they required much less maintenance, were durable and a bit more economical than wood. Some models have low gunwales to facilitate fishing from the boat; some can be highly customized. One maker even has doors. “I have to say that I loved the ability to step through a Pavati boat I was in recently,” Fletcher said, laughing. “Back in the day I could step out of a classic boat easily. Now, not so much. There’s room for many different drift boat designs, each best suited to their environment.”

For Roger Fletcher, however, there’s nothing quite like a wooden boat. “There’s a warmth in the wood, and a connection to the McKenzie,” he shared. “I’m a romantic about wood drift boats: boats taking shape by hands fondling wood, listening to the wood as it tells you what it can and cannot do, shavings falling around one’s feet and the odor of Alaskan yellow cedar or Port Orford cedar permeating the air. Sweet. Sweet. Sweet. If I could afford it, I’d cast a bamboo rod from a wooden boat. I’m old enough to appreciate the history.” Fletcher pointed me to a quote from Ted Leeson’s The Habit of Rivers that lyrically captures his sentiments:

“Like the steelhead, the drift-boat is the perfect union of form and function all beauty and business, and one of the most honest things on the planet. Few other craft will perform the same function, and none with such elegance. A whitewater raft will transport you downstream, but is sluggish and clumsy, handling precisely like what it is—an ungainly bag of gas. But the hull of a drift boat is geometric grace, a curvature in space defined by smooth arced planes that intersect like the vault of a cathedral. It holds no hint of ugliness. A drift-boat has a simplicity, a clearness of vision, and a sense of purpose so absolute that it might have sprung from the uncluttered heart of Shaker.”

Though the early McKenzie guides understood the advantages of rowing against the current and the need to maneuver laterally to avoid obstacles, achieving these goals with the “old scows” was at best a challenge.

Comments