Stories about a moment, or string of moments, that ignited a passion for fishing.

Autumn Harry may not have had a choice. She was born to love fishing. It was in her blood, just like it was in her ancestor’s blood. It helped that her dad was a Water Protector, and her mother worked at a local hatchery and monitored water quality.

But even young anglers born to love fishing can get frustrated.

One day after elementary school, Autumn’s mom picked her up to go fishing on the Pyramid Lake Paiute Reservation northeast of Reno, Nevada. Autumn, who is Numu and Dine and a member of the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe, cast and cast with little to show, grumbling louder each time.

“My mom told me, ‘Well, if you smile, and if you’re happy, you’ll catch a fish,’” Autumn said. “And so I threw on the biggest smile from ear to ear, and I sent out my cast, and I just kept that smile on the whole time, and then I had a fish on.”

Autumn was fishing in the famous Pyramid Lake, home of massive and vibrant Lahontan cutthroat trout and the Cui-ui, a native sucker. Her people are the Kooyooe Tukadu band of the Northern Paiute, which means Cui-ui Eaters. The lesson her mom taught her that day—that water is a place that brings joy—stayed with her.

But that innate love still grew over time. Like when, in 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic ripped across the country, hitting communities like the Pyramid Lake Paiute particularly hard, tribal leaders decided the shoulder-to-shoulder fishing on Pyramid Lake needed to pause. They shut down fishing on the lake to everyone except tribal members and residents. For eight months, Autumn focused on deepening her relationship with fly fishing in a space where no one watched.

“I got to the point where I knew exactly what depth to fish and where the fish are swimming and what they’re eating and where to cast,” she said. “It was also the time before vaccines, and we weren’t sure if we were going to survive. But I was out there every single day with my dad.”

Week after week for months the two of them cast their lines, laughed and kept fish for their people, delivering the fish to families who, because of the pandemic, no longer had access to their ancestral food.

What Autumn realized in those moments was that everything she’d been taught by her ancestors, her parents and the fish themselves, would soon become her future.

Autumn’s life is littered with stories of falling more and more in love with fishing, as are most of our lives. Maybe it’s a lesson from a family member, or particularly notable vacation or the time someone handed over a rod and said “try.” We all have that moment, or string of moments, that sparked a change and led us down a different path, one where fish, and fishing, would take the lead.

Lessons from a grandfather

Standing on the end of a dock as the sun glinted off the mayfly-covered water, my seven-year-old daughter and four-year-old nephew squealed at the same time. They cast their rods into the water and watched as 6-inch sunfish slurped their hooks, leaving behind a splash and a ripple. Their lines went tight, and my husband Josh told them to pick up their poles.

That moment felt, for Josh, like a scene from his childhood when he stood on the banks of a similarly reeded lake in Minnesota, this time next to his grandfather as the older Peterson told him to pick up his rod and hold his line tight.

And that’s what he did.

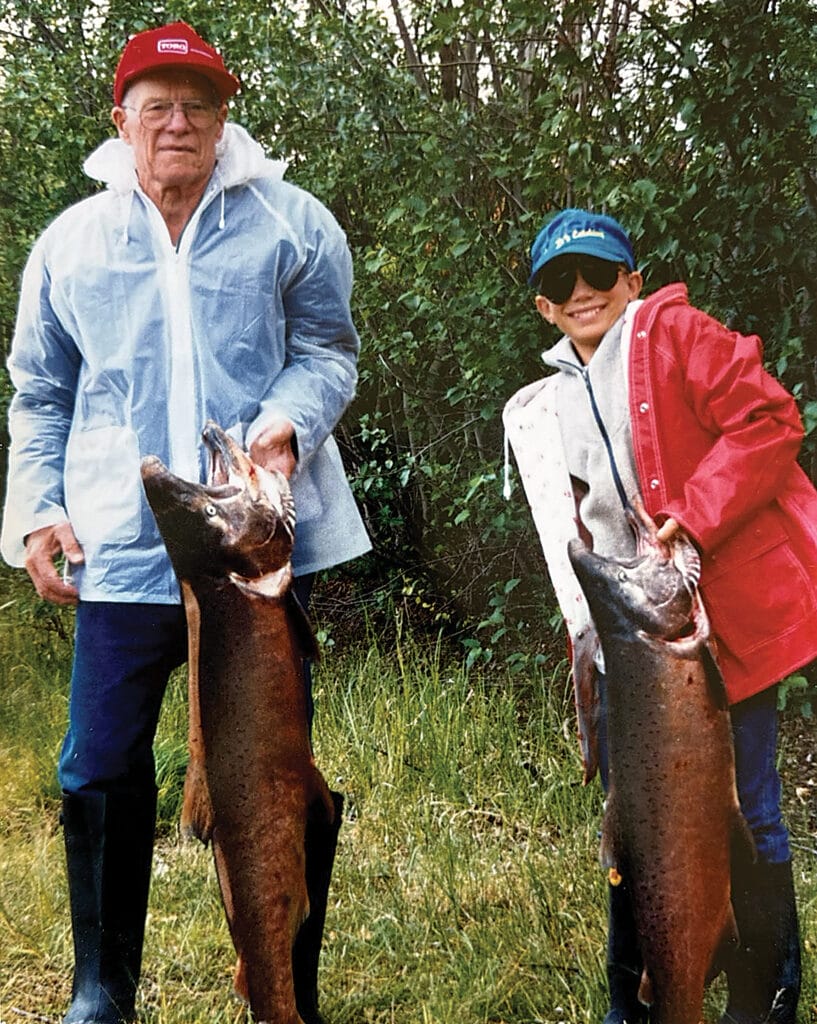

Over and over, day after day on summer visits from his home in Wyoming to see his grandparents in the Land of 10,000 Lakes, Josh would stand next to his grandpa and reel in sun fish. That little boy with too-big aviator sunglasses and an even bigger grin didn’t know it at the time, but he would turn into a trout fisherman, Alaskan fishing guide, and eventually a middle school science teacher. His love of fishing and teaching people to fish would turn into a career teaching science to the next generation.

And he traces it all back to those muggy Minnesota days, reeling in one sunfish after another, then carefully scraping their scales, emptying their bellies and breading and frying their flaky flesh in a pan of hot oil.

So when his little sister asked us to go back to Minnesota with her and her four-year-old son to teach him to love fishing, Josh had no choice but to say yes.

The trip became the first taste of fishing for our nephew, but may have, somewhat ironically, become what made our daughter into a fisherwoman. She, like Autumn, has spent her life fishing. From the time she could stand, she’s been casting into Wyoming’s streams, creeks, rivers, lakes, beaver ponds and even a culvert or two. But it wasn’t until that dock in Minnesota that all those lessons seemed to come together like a school of herring, taking shape as she realized the magic waiting for her underneath the water’s surface.

Figuring it out

As an adult, Matt Miller has built a life around water, fish and fishing. His interest in fish spans their natural history, their ecology and the simple thrill that comes from feeling a tug at the end of his line. He even wrote a book about it, called Fishing Through the Apocalypse: An Angler’s Adventure in the 21st Century.

But he’s much less interested in the hooked jaw of a trophy brown trout or pop of color from a rainbow trout than he is in the native fish swimming through whatever water he’s standing in or alongside. He wants to see and understand the fish that evolved in those streams, rivers and lakes.

While as a young boy growing up in rural Pennsylvania, he certainly loved to fish. But it wasn’t until his dad and a group of buddies took 14-year-old Matt on a fishing trip to Ontario, Canada, that he realized just how big a part of his life fishing would become.

“The fishing, by Canadian lake standards, wasn’t great, but I fished constantly, from sunrise to sunset every day,” he said. “It was one of those trips where the guys were playing cards and drinking beer, and I just did my thing.”

He took a tackle box full of big lures for pike, but after one pike on the first day, the bite stopped. So he found some smaller hooks to use for perch, crappie and rock bass, and he improvised with his baits, trying anything he thought could work. Then one day while eating lunch on an island, he took scraps of ham, wrapped them around a hook, and cast. A huge yellow perch bit.

“There were loons calling, and it was beautiful, and everything was there: the love of nature, of fishing, of dreaming of travel, it brought it altogether,” he said. “I realized this is what I want my life to be.”

Fishing for the future

Autumn’s journey with fishing didn’t stop after those months on the water, laughing and fishing with her dad and feeding people. She realized she could use what she knows, like her ability to pinpoint exactly how deep fish are suspended and what they will bite, to teach other anglers not only how to catch Lahontan cutthroat but also about the sacredness of water and the sacredness of fish themselves.

“My dad has this wonderful quote, ‘What is good for the fish is good for the people,” she said. “If the fish are good, then that means the water quality is good, that means the people are healthy.”

So in 2021, she became one of only three of Pyramid Lake’s Indigenous guides. She named her company Kooyooe Pa’a Guides, requiring anyone who books with her to say her people’s name for Pyramid Lake.

And like Matt, Josh, Miriam and maybe even my nephew, those moments that ignited Autumn’s passion for fishing keep growing, working in tandem as the fish teach her and the rest of us lessons about not only about how to catch and respect them, but also be in better relationship with the water.