We just released an issue of TROUT magazine that focuses most of its 100 pages on the need to remove four dams from the Lower Snake River. That was an easy call for me as editor because I think removal of the Lower Snake dams, thus giving a huge percentage of steelhead and salmon in the Lower 48 a chance for survival, will be the defining issue for this generation of anglers and others who care about native species.

The story that rocked the trout fishing community last week, however, was about how a glitch with a gate in the Hebgen Dam on the Madison River in Montana led to a fish kill that could have lasting negative impact on one of the nation’s premier fisheries. Anglers across America, and especially in Montana, were freaking out because one of the most fabled trout rivers in America was drying up because a dam wasn’t working properly.

Wait… on the one hand we want to get rid of dams, and on the other, we worry that a dam isn’t doing a good enough job to support a trout fishery? Isn’t that a contradiction, or at least a little, um, dam confusing?

It is. But that’s the fickle nature of the angling world we live in.

It’s easy for many to embrace the ideal of free-flowing rivers, unencumbered by dams. Let nature have its way like it was before people started messing with rivers, right?

Well… hold that thought for just a minute. There are obviously a ton of economic realities that need to be part of any discussion on large dam removals. But focusing just on the sport of trout fishing, consider the reality that trout fishing in America—particularly fly fishing for trout in America—would simply not exist today, even as a shell of its current self, were it not for the presence of tailwater hydroelectric dams.

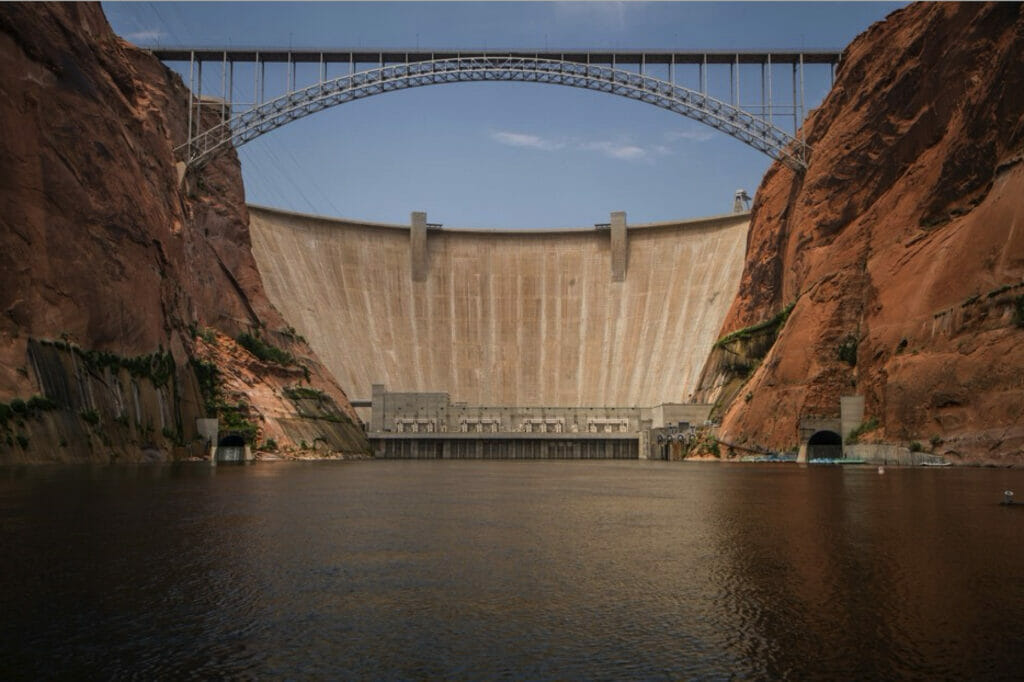

Many of America’s most legendary “trout” rivers are, in fact, tailwaters. The Madison. The Delaware. The Bighorn. The Holston. The Missouri. The Chattahoochee. The Henry’s Fork (of the Snake River). The Frying Pan. The Arkansas. The Green. The Colorado River at Lees Ferry in Arizona. The White River in Arkansas. The Sacramento. The San Juan. The Guadalupe in Texas. I could go on…

Wait… trout fishing in Texas? Yep. Because water released from the base of a giant dam remains in a constantly cool temperature zone that trout thrive in. And tailwaters are also bug factories, where caddis, and midges, mayflies and in some places stoneflies create a veritable smorgasbord for bug-eating trout. That’s why 99.9% of the hefty, bright-colored trout you see on the covers of glossy magazines are caught within 20 miles or so of the base of a hydroelectric dam somewhere. You can bank on that.

You can also bank on the fact that all the rods, reels, lines, flies… all the lodges, boats, paddles, everything that comprises the multi-billion-dollar realm of recreational trout fishing would be a fraction of what it is now, minus tailwaters.

Some might think that would be a good thing. For others, that would be catastrophic.

Just like the fish. In some places they thrive under dams, and in others, a dam is their worst enemy. One thing we Just as for the fish. In some places they thrive under dams, and in others, a dam is their worst enemy. One thing we do know for certain is that dams are almost always “bad” for anadromous fish (fish that run to the ocean and back into freshwater to spawn). And the equation is pretty simple to understand. We’ve already seen it play out in places like the Elwha River in Washington state.

Steelhead in the river. Dams built. No more steelhead in the river. Dams removed. Steelhead back in the river. Simple stuff.

For me, it’s all about picking and choosing battles very carefully and understanding that dams can have different effects on fisheries in different places.

Dams that block steelhead and salmon like the four on the Lower Snake River? Remove them. Dams that support a tailwater fishery like the Madison? Well, that’s a different kettle of fish, but maybe with some of the government’s planned infrastructure spending, we should at least see that those aging dams still work.