Editors note: This is the second in a three part series looking at the myths perpetuated in the national discussion about national monuments and the Antiquities Act.

By Corey Fisher

The issue of national monuments and the Antiquities Act tends to elicit passionate responses, both for and against. It also spurs misconceptions. Here are some of the most widely perpetuated myths about national monuments.

Monumental Myth #4: National monuments lock out the public.

Fact: Most National Monuments proclamations honor valid exist rights, such as for oil and gas leases, grazing, and rights-of-way. National monuments are a flexible type of land designation that can allow for broad access to a variety of multiple uses in ways that are compatible with identified values in need of protection. In essence, national monuments typically keep it like it is, ensuring future access to current uses and activities if they align with the overall purpose of the designation.

Following a designation, site-specific land management plans are created in collaboration with state and local governments, federal agencies, and the public. Input is sought at the beginning of the process, and a draft plan is made available for review and comment before a final decision is made.

Monumental Myth #5: National monuments are created in secrecy without public input.

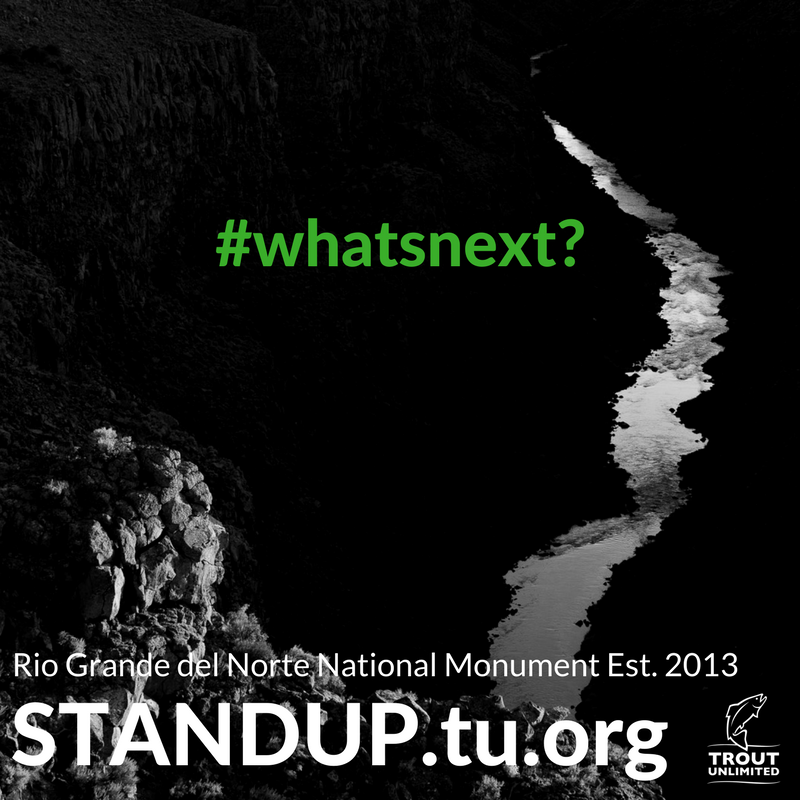

Fact: The designation of many national monuments have come after legislative proposals to conserve public lands languished in Congress for years, sometimes decades. In many instances, monuments have been designated only after robust public debate and support from a diverse set of local interests. For instance, when Rio Grande del Norte National Monument was designated in 2013, it received local and statewide support from local elected officials, state and national sportsmen’s groups, grazing permittees, and the New Mexico congressional delegation representing the area.

Monumental Myth #6: National monuments are the same as a national park.

While some national monuments have gone on to become America’s most beloved parks, such as Zion and Grand Canyon National Parks, Congress is the body that creates national parks and it is a decision and action completely separate from the designation of a national monument. Most modern national monuments do not become parks and a national monument can only be redesignated as a national park if Congress passes legislation to do so. Unlike national parks, most monuments in the West are managed for multiple use by the BLM or Forest Service. Learn more about different types of land designations.

Monumental Myth #7: National monuments are supposed to be small.

Fact: Six months after signing the Antiquities Act, Teddy Roosevelt created the first “large” national monument with the 60,776 acre Petrified Forest. Two years later he set aside 808,120 acres as the Grand Canyon National Monument. Development interests fought the designation and lost in the Supreme Court, establishing the precedent for monuments to protect both large and small areas. Numerous presidents of both political parties have gone on to create national monuments encompassing large areas with important biological, ecological, historic and cultural values, including hunting, fishing and recreation.

Monumental Myth #8: National monuments are an unconstitutional abuse of executive power.

Fact: Presidents can create national monuments only because it is an authority granted by Congress through the Antiquities Act. This delegated authority has been used to create national monuments by sixteen presidents, eight Republicans and eight Democrats.

From the earliest uses of the Antiquities Act to some of the most recent, Congress had the first opportunity to act on community-driven initiatives intended to conserve important public lands. If Congress does not take action, the president can use the Antiquities Act to try and accomplish the same goals. This approach – using the Antiquities Act to break congressional deadlock – continues to be utilized today.