Greg McReynolds

Dec 12, 2022

Beneath the slack water, it’s all still there. The main channel, braided in places, lined with reef and rock, hemmed in with granite and the dark loam that fueled the old orchards. Only 100 feet of water, less in most places, inundates the river below. Upriver from Wawawai near Granite Point, there is a submerged top rope anchor. Before Lower Granite dam was finished in 1975, climbers worked a route now invisible below the surface of the reservoir.

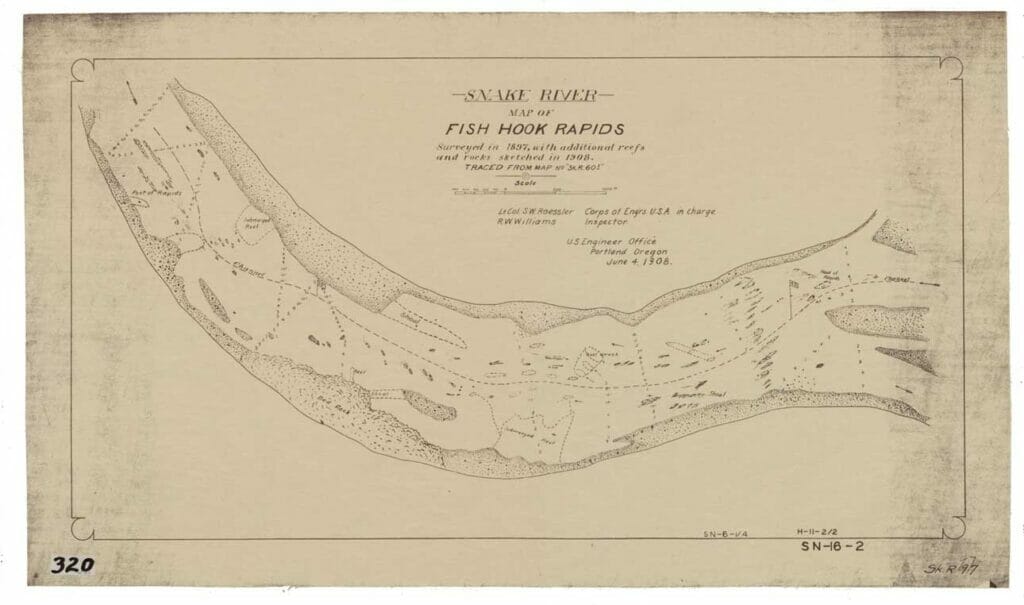

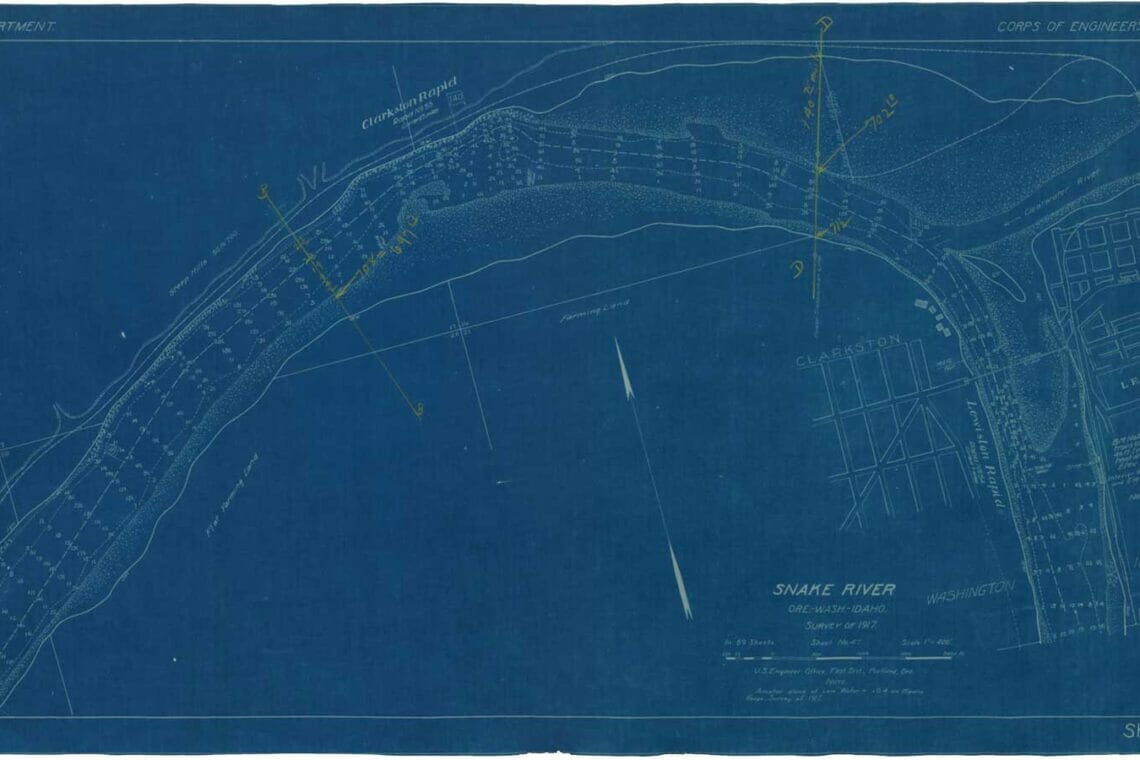

Lewiston Rapid, Clarkston Rapid, Upper Swallows Nest, Dry Gulch and Fish Hook, Five Mile and Pine Tree—somewhere beneath the water and the silt, those and dozens of other rapids still exist, waiting to re-emerge.

At home, gear is strewn across house and garage; the cooler is locked in the deep freeze of a local grocery store. I am in the frantic pre-launch stage for a Grand Canyon trip, only days ahead. But for some reason, I can’t get my mind off the 140 miles of river hidden beneath the reservoirs of the lower four Snake River dams.

The campaign to remove the lower four and recover the largest and most important piece of habitat left for salmon and steelhead in the Lower 48 is rightly focused on the anadromous fish that once returned to Idaho’s high country in the millions. But for those of us who are river runners, boat builders and lovers of whitewater, the allure of sections of the Snake River not seen for generations has its own special appeal.

And the Snake, like the Colorado, is a storied western river. John Wesley Powell on the Colorado and Lewis and Clark on the Snake. The iconic Grand Canyon of the Colorado, which is eclipsed in depth by Hells Canyon on the Snake. Wild country and white water have a powerful pull, and both the Snake and the Colorado have tugged at our collective imagination across the centuries.

It’s 280 miles from Lee’s Ferry to Pearce Ferry on the Grand Canyon. This is a whitewater trip pretty much unmatched in the Lower 48. Gates of Lodore is only 44 miles, 73 if you add in the unpermitted miles below Flaming Gorge dam. You could keep going and add Desolation Gray Canyon for another 84 miles, but you would need to draw two, separate, hard-to acquire permits. The Main Salmon is 81 miles, Middle Fork of the Salmon is 114. With a Main Salmon permit, you could start at the headwaters and after turning the corner at the Snake River, make nearly 400 miles to the slack water at Lewiston. The Missouri and the Yellowstone are long floats, but once you leave the mountains, they are mostly flatwater rivers.

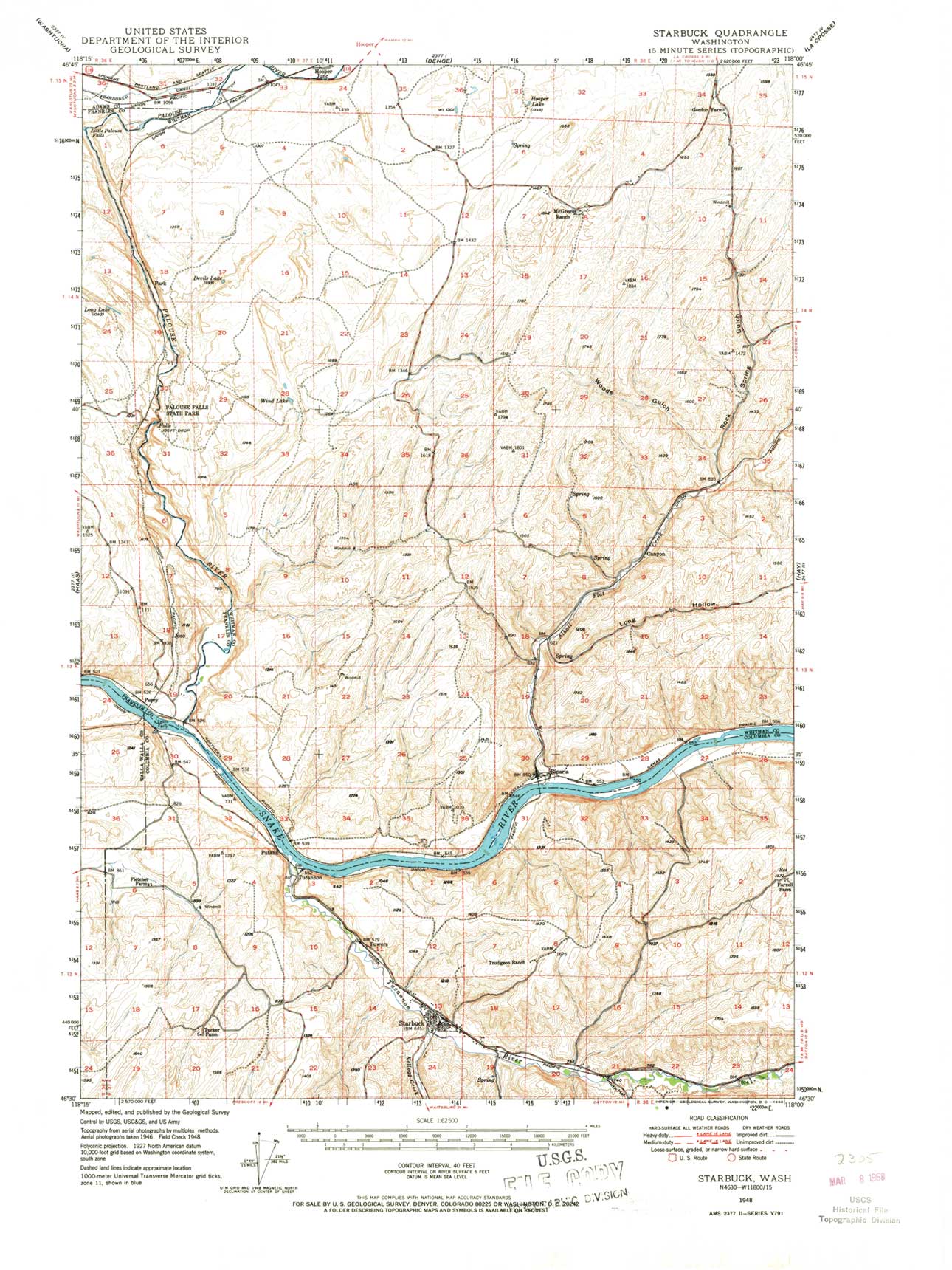

From Hells Canyon complex to the Clearwater is 108 miles. Removing the lower four Snake River dams would add at least another 140 miles to that total for a trip that is longer than Lee’s Ferry to Diamond Creek on the Colorado. Without the dams, floating the Main Salmon from Challis to Pasco at the confluence with the Columbia would be possible, clocking in somewhere around 550 whitewater miles.

More than 140 miles of new river, not seen for generations, unpermitted (at least at first) is a dream for many of us who spend an increasing number of hours applying for float permits that are getting statistically harder to draw.

My home water is the upper Snake River which we Idahoans stubbornly call the South Fork from the Wyoming border until it merges with the Henry’s Fork. The Snake River below Henry’s cuts through the rugged rift of the Snake River volcanic plain. Along the river, barn swallows nest in the basalt remnants of a 10-million-year-old cataclysm. The river ambles by, as if it hadn’t spent eons cutting away billons of tons of volcanic rock shoved skyward by shifting tectonic plates.

A river testifies to redemption through perseverance. A river is a drop, a trickle, a torrent. It is an unstoppable force, unbothered by the passage of time. Water, like rock, operates not in years or decades, but in eons. On the Colorado, the stratified layers laid bare by the river are a geologic clock, cataloging the passage of millennia.

The existence of that clock makes me sure that the lower four Snake River dams will come down. In The World Without Us, Alan Weisman speculated that dams would be short-lived in a world without humans. “In far less time than it took us to run out of codfish and passenger pigeons, every dam on earth will silt up and spill over,” Weisman wrote.

The lower four Snake River dams are coming down, of that I have no doubt. The fiscal reality of aging infrastructure means that the fate of the lower four is already written. Designed in the 1950s, built in the 1960s and 1970s, they are already bumping up against the end of their life. Since they were designed, we have exceeded the speed of sound, put a man on the moon, landed a probe on another planet and seen the origins of the universe from a telescope orbiting the sun. Ice harbor, Lower Monumental, Little Goose and Lower Granite, are no longer the technology of the future. These four dams have become an anchor, holding us in stasis while we wait for a living, breathing river to reveal itself from the depths of the expired reservoirs.

The question is not if the dams are coming down, the question is only when and if it will be in time to save plummeting populations of wild Snake River salmon and steelhead. Idaho’s salmon are up against it, but I feel it too. The Snake River below Lewiston will return, but for the salmon and for all of us who yearn to know this river, time runs short.

Comments