By Dave Atcheson

Most Alaskans are painfully aware of the recent downturn in king salmon runs on many of our streams. The numbers of returning Chinook salmon have remained alarmingly low for the last several years, prompting fishing closures in many areas, including the previous season’s closure of the entire Southeast region.

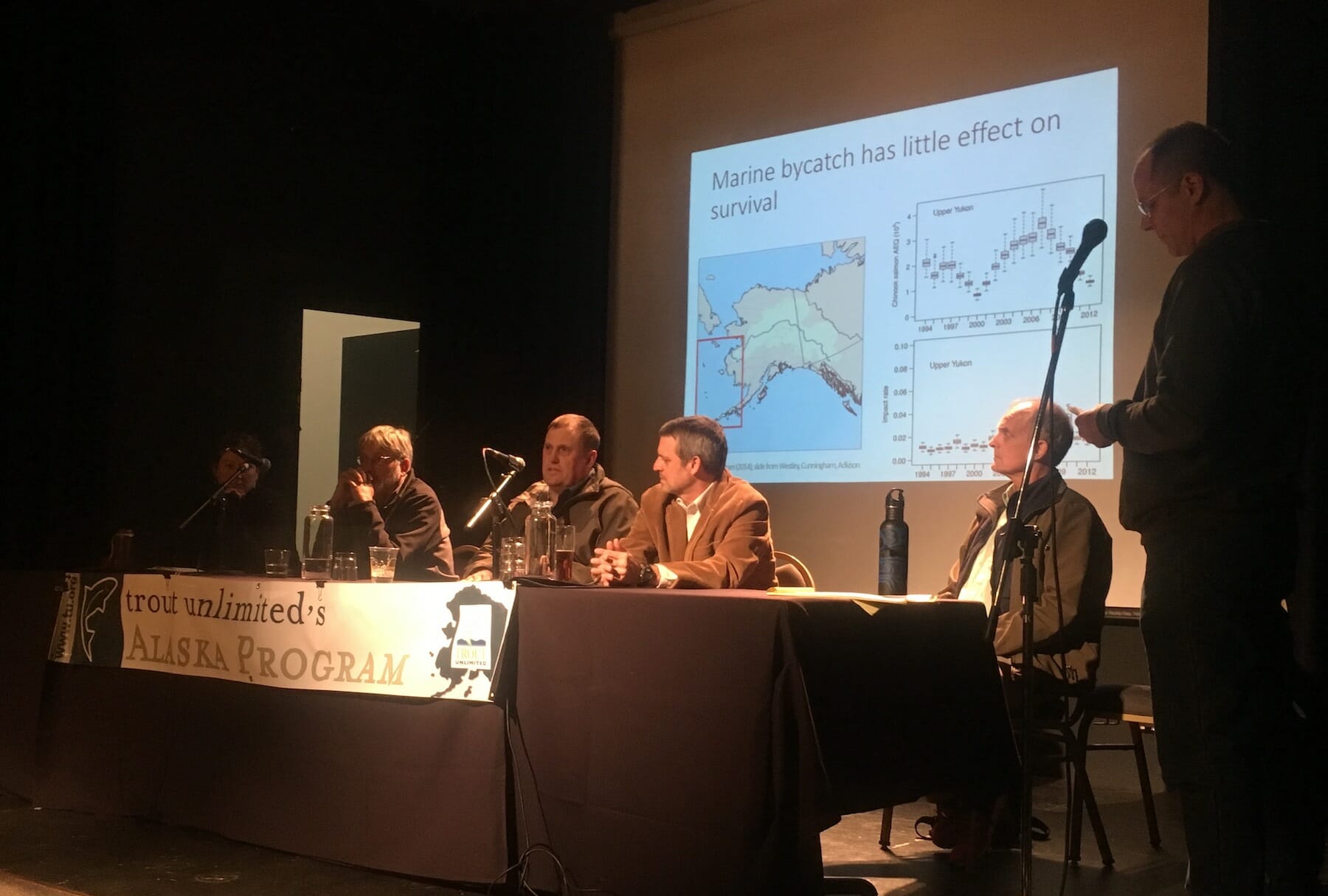

It was with this in mind that Trout Unlimited organized and hosted a Chinook salmon presentation and panel discussion on October 17 at 49th State Brewing in Anchorage.

Presenters included Ed Jones, the Alaska Department of Fish and Game’s Chinook Salmon Research Initiative Coordinator, who discussed current recent trends, how populations around the state are doing, how they’ve done over the past few seasons, and a look at last season.

Robert Ruffner from the Alaska Board of Fisheries discussed how the board process works and how management decisions might affect populations.

And Megan McPhee, a professor at the College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences at University of Alaska, discussed possible reasons for recent declines, and described past research she has been involved in as well as what research is currently being undertaken.

The three presenters were joined on the panel by Alaska Department of Fish and Game biologists Bill Templin and Jim Hasbrouck for a question-and-answer session.

While this was an excellent opportunity for the average Alaskan to sort out what trends have been occurring with regards to king salmon in recent years, and to learn from the experts, the big take-away from the evening’s event was that there is not one glaring reason for the recent downturn in Chinook size and numbers.

Likely there a variety of reasons that, in combination, are resulting in the decline. These include: warming ocean temperature and climate change; ocean carrying capacity, which may be diminished by the expansion of hatchery stocks; high seas interception of stocks; commercial bycatch; and habitat degradation.

It was also suggested that the decline in Chinook may even be a natural occurring fluctuation, a cyclical downturn much like coho stocks experienced in the 1990’s.

With a limited amount of time, the topic of what future research needs to be conducted was only briefly touched upon. Panel members agreed that much work needs to be done in understanding the salmon marine life stage, including near-shore survival rates.

With state revenue declining and with the current federal administration, there will likely not be much government money forthcoming to further fund the expensive research that is needed.

Chinook salmon, however, are of such great value — culturally and economically — to the people and communities of Alaska that action must be taken in order to protect this important resource and curb ongoing declines.

The State of Alaska, the Federal government, and those of us in the private sector, should in the near term take proactive measures that science has already demonstrated support healthy salmon runs.

This includes protecting key spawning and rearing habitat, maintaining clean water, and ensuring free flowing streams, which allow for migration of both juvenile and adult salmon.

While further research needs to be done regarding both the fresh-water and ocean environments, in many cases science has already told us what we need to do, or at the very least what not to do, to ensure the freshwater component of Alaska’s salmon runs. It’s up to us and the time is now to see what we all might do in order to retain this iconic symbol of our state and mainstay of Alaskan fishing.

Dave Atcheson works with Trout Unlimited’s Alaska Project. He lives in Sterling.