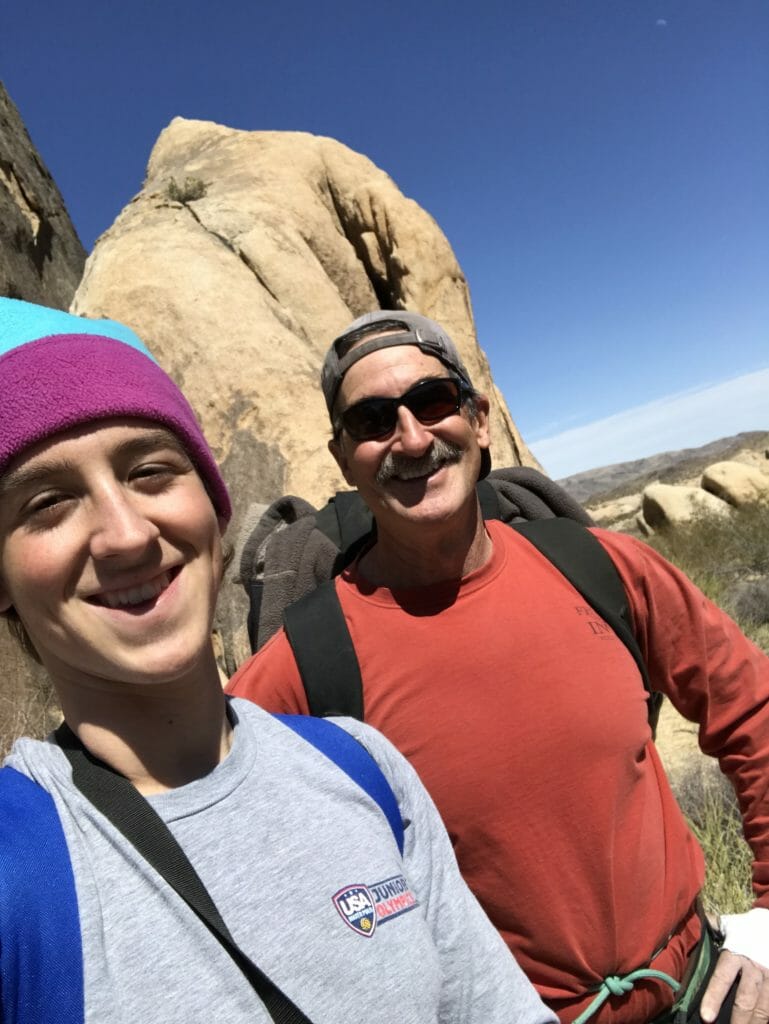

Photo: The Steelhead Whisperer and his daughter on California’s Big Sur River.

I spent Father’s Day this year not fishing.

That was fine with me, though. My son was with me and we were at 7,500 feet in the Sierra Nevada range, where winter had not yet gathered up all of her train. And we were doing something that’s as much fun as fishing—and a whole lot scarier.

We went up to an area festooned with granite domes and outcrops of a burnt orange hue. This landscape is magical at all times, but at sunset it glows as if sitting atop a giant forge.

It’s also rife with streams, most of which hold trout, most of which are small and wild and beautiful. I have fished with much satisfaction all over this area for three decades.

But our activity of choice for the weekend was technical rock climbing. Not like Alex Honnold in the movie Free Solo—we used ropes and safety anchors. We ascended a four hundred-foot high crack system on a formation called the Golden Toad. The climbing was pretty easy, by today’s standards.

Sometimes when you are standing in a stream or on its bank, your rod at your side or following your fly downstream, you see unexpected things, or think about things far from that place. It’s the same when you’re on a large wall of featured rock, crystals in its surface glinting in the sun.

We found, for example, a tiny frog wedged in a crack, and whistling swifts stuffing themselves into crevices below our feet. We watched puffs of smoke rise intermittently from a forested ridge to the west of us, likely from embers left by a recent lightning strike.

And sitting on a ledge near the top of the formation, I thought about my father, who recently passed away.

Dad wasn’t much of an outdoorsman. He was a businessman and an academic, and his preferred form of outdoor recreation was sailing. I didn’t learn from him how to fish, or how to rock climb, or any of my other preferred ways to enjoy the out-of-doors, actually.

The skills I did learn from him, though, were more valuable: how to treat people, how to do any job to the best of your ability, the importance of integrity, how to live beyond your own needs and wants.

Dad stood only 5-foot 10-inches, but he was like the Colossus of Rhodes to his three sons.

The one time my father took me fishing was more or less a disaster. My brother and I were perhaps 10 and 8 years of age and, thanks to mornings with our grandfather on Florida’s Gulf Coast and summer days spent on the Wood River in Idaho, loved fishing. We wanted to catch a salmon, so Dad got us on to a party boat to fish the waters of Monterey Bay for kings.

We got up before dawn that morning and, because Dad was a big fan of all three meals, went to Denny’s for a massive breakfast. As it happened, there was a sizeable northwest swell running that day, and as soon as we cleared the harbor the boat was rolling and pitching pretty good.

My brother and I were quickly “green around the gills.” Diesel fumes competed with the pungent aroma of cut-bait anchovy for the more pernicious influence on our constitutions.

And my father—a lifelong sailor who had sailed in open-ocean conditions for weeks at a time and who had never gotten seasick, ever—apologized to his sons and leaned over the railing to donate his breakfast to the sea.

I can’t even remember if we came home with a salmon.

Dad was born in 1934 and, like all of that generation, shaped by the Great Depression and World War II. Also like many from that era, he was dedicated to a value-driven life that contributed to civic, spiritual and societal causes. When I came to work for Trout Unlimited, he became a member of TU, even though he didn’t know a brookie from a brown.

Sitting on that ledge, it came home to me how much I would miss our conversations, which inevitably began with him asking, “How’s the fishing?”

My son popped onto the ledge, a big smile on his face. The difficulty eased there and shortly we were on the summit. My father was there, too. He was there as we made the sketchy downclimb on the northeast corner of the formation, and as we kicked steps and slid down the snowfield still cloaking the slabs at the base. He was there as we put our faces to the stone to drink pure snowmelt where it started its long journey to the San Joaquin River.

My father was there as my son and I drove over Chiquito Creek, a few miles from the Golden Toad, and reminisced about the day I had taken my son fly fishing there when he was 8 years old.

My son had yet to fish with a fly rod, so we tag-teamed the exercise of casting and stripping in line. The creek was running high that day but we managed to catch a handful of vigorous rainbows and brookies in the margins.

At length I spotted a nice eddy below a log that had fallen across the stream. The spray coming off the creek had rendered the log slick, but I decided it was a good idea for the two of us to sidle out on it anyway and drop a caddis into that eddy.

On our first attempt to flip the fly into that tantalizing swirl, I slipped off the log on the upstream side, dragging my son off with me. I landed upright in waist-deep water, and managed to keep my son from going under. But my prized 3-wt dropped into the creek on the downstream side of that log, never to be seen again.

It’s one of my son’s fondest memories—and one of mine.

Sam Davidson is the communications director for TU’s California Program.