I’m in Little Rock, Ark., this week for the Outdoor Writers Association of America conference. Our hotel is situated right on the banks of what looks to be an angry Arkansas River.

Years ago, I worked as an editor and reporter for a couple of small newspapers about 1,000 miles away, near the headwaters of the this great American river. The little town of Buena Vista (pronounced Byoona Vista if you live there) is but 50 miles or so from the actual start of the Arkansas as it tumbles off of Fremont Pass in cental Colorado and flows south near the town of Leadville, through Buena Vista and the new Browns Canyon National Monument. It then winds through Salida and eventually the Royal Gorge and Pueblo, picking up small tributaries along most of its upper course. After leaving Pueblo Reservoir, the Arkansas meanders across the prairies until, here in the state of Arkansas, it becomes a big, muddy southern river.

This last winter was a record-setter for the folks back in Colorado, and they can lay claim to the fact that they’re sending quite a bit of the water that is swelling the river’s banks here in Little Rock so far downstream. It’s been a great year for snow melt, and I suspect it’s going to be a pretty lively rafting and kayak season on the river near its genesis.

The Arkansas in Colorado is a playground for boaters and, at certain times of the year, it’s a great river for wild brown trout. It is, after all, home to the famous Mother’s Day caddis hatch.

But I’ve always looked at the Arkansas as a river with challenges. Within sight of where it begins as spring water and melting snow, the old Climax molybdenum mine has literally shaved off the peaks of the Mosquito Range above the river. Hundreds–maybe even thousands–of small mines, mostly abandoned and shuttered now, dot the mountainsides around the river’s upper reaches, as well as along its tributary streams that start high in the Sawatch and Collegiate ranges and drain some truly wild, high-elevation country.

Those old mines, to this day, drain heavy metals into the Arkansas, and they very likely will for years to come. There are efforts to curb their impact–and better fishing in the river’s lower reaches testify to those efforts being at least somewhat successful–but the river will, for the foreseeable future, always be a conduit for abandoned mine runoff.

Nevertheless, it’s a beloved resource in Colorado. Saturday night, those of us attending the conference here in Little Rock got to listen to music and dine on some spectacular southern-fried catfish as the river–brown and roiling from a seriously wet spring and, of course, from Colorado’s immense snow melt this year–flowed by within just a few feet.

As much as Coloradans love the Arkansas, I would venture to say that Arkansans are pretty fond of it, too. Bridges over the big river draw tourists seeking selfies with the city skyline in the background, and walking paths and greenbelts abound. It’s not just a feature here in Little Rock. It’s the feature.

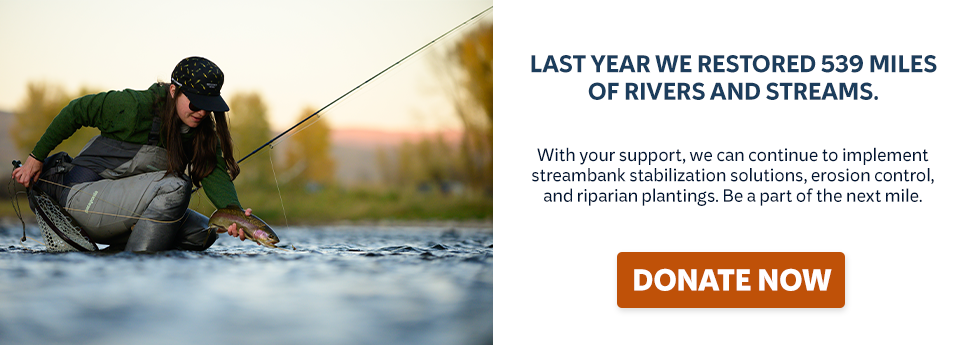

At TU, we do work on a lot of rivers–some just near the source, where the cold water flows and where the trout swim. But our work in the little tributaries and trickles that come together to make mighty rivers impacts those big waters, often many miles away from where we clean up abandoned mines or restore streams to their natural course and help make fishing better.

All across the country, there examples where small projects in headwater streams contribute to quality water downstream, where these rivers provide for everything from industrial use to drinking water to shipping. The Arkansas is no different.

Just a few years ago, TU worked to protect Browns Canyon as a national monument–local stakeholders who understand the value of protecting wild landscapes and intact, healthy watersheds came together and convinced then-President Obama to create the monument that today defines the canyon country of central Colorado.

And that, of courses, protects the quality of the water as the river flows 1,000 miles away in downtown Little Rock, where families gathered over the weekend to listen to music under sultry southern skies and enjoy the river as it wanders on by en route to the Mississippi.

Rivers don’t just connect places. They don’t just provided a path for water from the highest mountains to the lush southern woods.

Rivers connect people, too. And that’s a lesson we just can’t learn enough.