The author, wade fishing the Trinity River.

By Sam Davidson

A guy I didn’t know die

d recently while wade-fishing the lower American River near Sacramento. One moment he was there, the next he wasn’t.

Impossible to say, exactly, what happened, since no one witnessed the incident. Apparently, he was a newbie to wading, likely slipped and filled his waders and got sucked into a hole.

As the Tralfamadorians say in Slaughterhouse-Five, so it goes.

Fishing doesn’t have the reputation of being an acutely unforgiving activity, on the order of, say, rock climbing or wingsuit paragliding. But this sort of accident is not infrequent, especially at this time of year when river flows are high from snowmelt runoff.

I’ve had a few near-misses over the years, and have seen other anglers have mini-epics. And I am not talking here about hooks-in-the-eyebrow or sprained ankles on the bank—I’m talking about too-intimate encounters with the water.

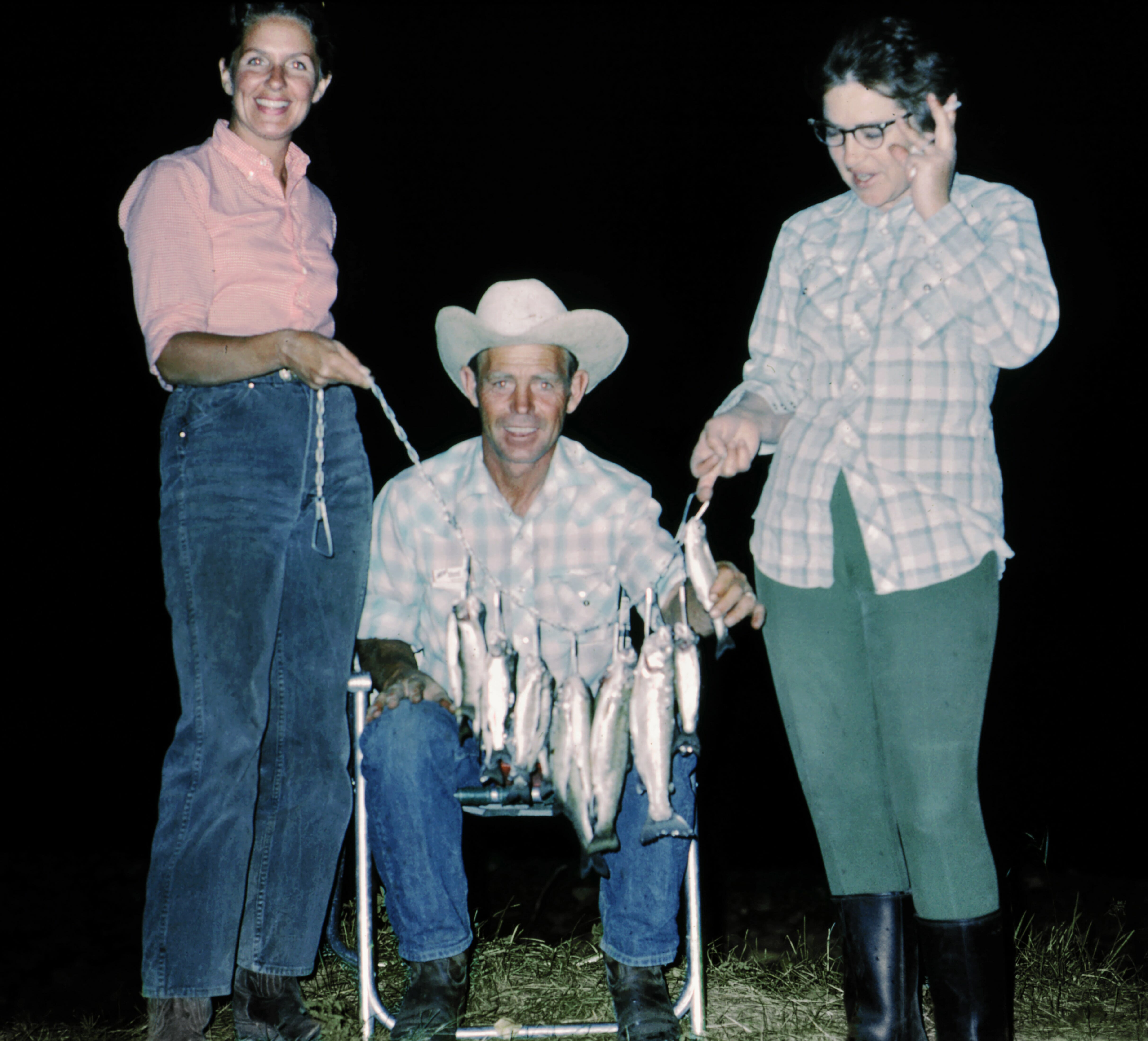

The man who taught me how to fly fish: Harold Johnston with a stringer of Wood River trout, 1968. My mother is at left in the photo and Harold’s wife Frances, an accomplished angler herself, is on the right.

The first time I began to think of wading in a river as something that might not be perfectly safe, I was maybe 10 years old. It was July or August and my family was camping on the banks of Idaho’s Big Wood River. My younger brother and I would get up early every morning, dig worms from the loam, and march off to catch trout for breakfast, wading the river with impunity—and without personal flotation devices.

One day, after a brunch of brook trout rolled in corn meal and pan fried in butter, my youngest brother, age four, got loose and clambered into one of the truck tire innertubes we had rented for lounging in some nice slack water a little way upstream of camp. The river became a riffle just below that section and my brother quickly got into the main current of it. I remember the family watching dumbfounded as he floated by the camp, then latched onto a snag just before going out of view.

The innertube stayed with him briefly, then spun away downstream.

I was still damp from the morning fish-out, so I either volunteered or was ordered—I don’t remember which—to retrieve him.

I think the water might have been about chest high by the time I reached the snag and my brother, who was, as I recall, remarkably unconcerned. I got him on my back and ferried him to the bank. I remember being a little sketched out while wading back, but we made it.

No one made a big deal about this incident, but in thinking about it now, it seems like it could have been disastrous. However, other things had to happen to me before I became more cautious while wade fishing.

Near the site of the wild boulder ride, Merced River canyon.

One was a dunking on the lower Merced River downstream of Yosemite National Park. This segment of the river flows for seven miles through a deep canyon and harbors some truly massive brown and rainbow trout. It has all kinds of pocket water, buckets, and tailouts, but the wading is tricky. One afternoon I was fishing alone, trying to reach some sexy water well-guarded by a steep bank and maples and willows at the river’s edge. Side-stepping down the bank in full wading gear, I eventually stood on a large, flat boulder perhaps eight feet above the water.

What I couldn’t see was the boulder had been undercut in its perch by recent high flows. Suddenly, with a grinding noise, it collapsed beneath me. I had just enough presence of mind to leap away as it plunged with a roar into the river. I landed in the water in a pushup position, facing downstream, rod still clutched in my right hand.

My prized Powell fiberglass 5 wt snapped on impact in the butt section. The shock wave of the boulder’s impact washed over me. I felt the frigid water flow into my waders and down my torso.

Fortunately, the current was lethargic there. I came up sputtering and dog-paddled toward the bank. I hauled myself out of the water, the majority of my rod dragging behind me.

Thanks to having cinched my wading belt snugly, and landing in the water with my head downstream of my feet, not much water made it down my waders into my nether regions. I was scraped and shaken but, except for my rod, intact.

That was maybe the worst, but certainly not the last of my mishaps while wading. On one visit to the infamous Pit River in northern California—like pretty much everyone else who has ever fished there—I took multiple plunges to my armpits seeking a good high-sticking stance among its mossy boulders. Each time I had to struggle back to the bank, find a stance amid the thickets of blackberry and rattlesnakes, and strip off my boots and waders to drain them of water and strands of aquatic vegetation.

Another time, on the Madison River, I lost my footing while retreating in waist deep water from a close encounter with a young bull moose and went for an impromptu ride. I was wet-wading so didn’t have to worry about my waders filling and dragging me down—I only had to fret about catching a foot in a submerged tree limb and getting sucked under that way. The moose snorted at me as I floated by in the lawn chair position.

The log that spit me off. Public lands fishing at its finest, central Sierra.

Then there was the time I was fishing with my nine-year-old son on a small Sierra creek. It was June and the stream had plenty of juice. I saw a sweet eddy against the far bank. A fallen log provided a good position from which to dap an elk hair caddis in it. My son and I sidled out on the log, my fingers dug into the back of his britches. Our perch was slick with spray. As I prepared to help my son drop the fly into the eddy, I slipped violently off the log, pulling my kid off with me but losing my grip on the 3-wt. The breathtakingly cold water was chest deep there and I hoisted my son above the fray as I struggled to the bank. I never found the rod.

Things can go sideways, or upside-down, pretty darn quick when you wade into the water with a rod in hand. I’m lucky that I’ve always emerged mostly unscathed from my wading adventures. The guy on the American River wasn’t so fortunate—a tough reminder to us all. As the sergeant in Hill Street Blues would urge at the start of every shift, “Let’s be careful out there.”

Sam Davidson is TU’s communications director for California and Oregon. He is still wondering where that 3-wt went.