The Nacimiento River at peak winter flow, central California.

By Sam Davidson

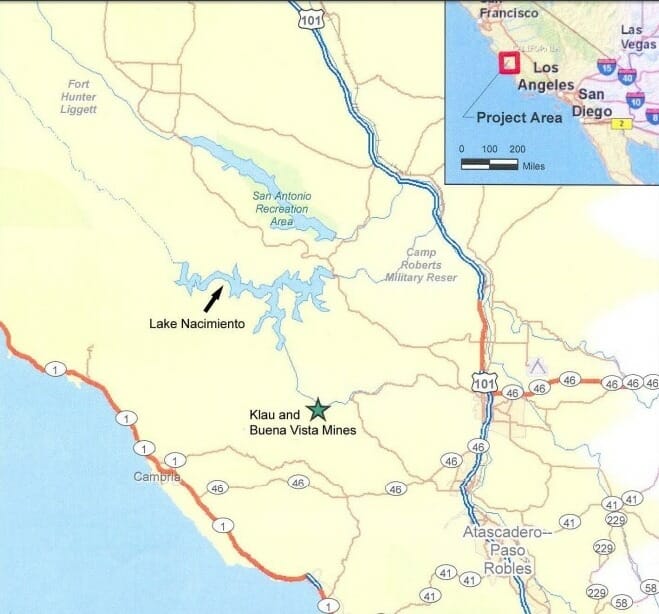

A recent telephone call with the Steelhead Whisperer got me fired up. His brother had been car-camping around the central coast, and had seen people fishing in one of the streams that swerve out of the Santa Lucia range and through the oak studded savannah of Fort Hunter Liggett.

This stream, which masquerades as a full-blown river during the winter wet season but otherwise assumes the character of a creek, has one of the prettiest names anywhere: the Nacimiento River. Nacimiento (pronounced Nah-see-mee-ento) is Spanish for “source of a river.”

Locals refer to it as “the Naci.”

I hadn’t fished the Naci for years. It’s not an epic trout stream by any means, but there is always an adventure to be had in unfamiliar territory. I decided a quick visit was imperative. My enthusiasm was such that my wife, a more circumspect angler, caught it and promised to outfish me if I brought her along. Who can say no to that?

Prior to 1957, when the Nacimiento River was dammed some eleven miles from its confluence with the Salinas River, it had steelhead in at. You wouldn’t imagine this, if you were to observe the river in late summer. Typical for many streams that originate in the coastal ranges of California, the Naci dries back in some sections into pools with little or no streamflow during the hot, dry summers.

Prior to 1957, when the Nacimiento River was dammed some eleven miles from its confluence with the Salinas River, it had steelhead in at. You wouldn’t imagine this, if you were to observe the river in late summer. Typical for many streams that originate in the coastal ranges of California, the Naci dries back in some sections into pools with little or no streamflow during the hot, dry summers.

Yet the Naci once provided some of the best spawning and rearing habitat for steelhead in the Salinas River watershed. A 1912 academic paper noted the presence of steelhead spawners there, saying “…especially good fishing may be had in Nacimiento and San Antonio Creeks” (Snyder 1912, p. 70).

My wife and I tried to imagine bruiser adult steelhead in the skinny water the Naci offered up in the hush of the late July heat, as we tossed small dries at wild and stocked rainbows.

Upstream of the boundary between Fort Hunter Liggett and the Los Padres National Forest, where it’s fishable, the river is no more than a few feet wide in some places. And the flow was miniscule. Yet the water was cold and the trout lively, thanks to the river’s spring-fed source near Cone Peak in the Ventana Wilderness.

Pretty much every likely pool and shaded run held trout. The stockers hung in the tailouts and rose languidly for size 18 elk hair caddis and royal Wulffs, while small wild juveniles slashed mightily at anything that ticked the surface.

A blend of madrone, oak, bay, grey pine and riparian growth limited wading and made casting tough. We donated a few of our offerings in thanks for their fragrant shade. The gnats locally known as “eye flies” were, shall we say, industrious.

We saw exactly zero other anglers.

All in all, a fine outing with rod and reel. Driving back in the early evening, I should have been relaxed—and I was, mostly. But I was also disquieted, because the Naci is exactly the kind of trout (and steelhead) water that could lose water quality protections under the federal Clean Water Act, if the Trump administration has its way.

For thirty years after its passage, the Clean Water Act was interpreted to apply not only to mainstem rivers and lakes, but also to smaller water bodies and streams that may not remain wet year-round. Two disjointed Supreme Court cases in the 2000s created confusion about the reach of the law. The so-called Clean Water Rule, finalized in 2015, used more than a million public comments and 400 pages of scientific record to clarify that smaller tributary streams and wetlands, some of which go dry seasonally but are nonetheless vital as habitat for fish and wildlife, are protected for water quality under the landmark 1972 law.

For thirty years after its passage, the Clean Water Act was interpreted to apply not only to mainstem rivers and lakes, but also to smaller water bodies and streams that may not remain wet year-round. Two disjointed Supreme Court cases in the 2000s created confusion about the reach of the law. The so-called Clean Water Rule, finalized in 2015, used more than a million public comments and 400 pages of scientific record to clarify that smaller tributary streams and wetlands, some of which go dry seasonally but are nonetheless vital as habitat for fish and wildlife, are protected for water quality under the landmark 1972 law.

But in February of this year President Trump issued an executive order to toss out the Clean Water Rule. Recently the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s took the next step in support of Trump’s order by opening a 30-day public comment period on the proposed action.

Trump’s repeal of the Clean Water Rule matters for anglers because nearly sixty percent of all the stream miles in this country are classified as small, headwaters or intermittent, and some states do not have their own water quality protection statutes. California, fortunately, does have its own water quality law, and in response to the Trump administration’s actions has vowed to adopt new protections for water quality, especially for wetlands.

We can’t ensure good water quality for trout, or drinking, or any other purpose in our larger rivers and lakes if we don’t protect water quality in their sources.

(L) Old mines have caused toxic levels of mercury in Lake Nacimiento, lower Nacimiento River.

(L) Old mines have caused toxic levels of mercury in Lake Nacimiento, lower Nacimiento River.

The Naci is, in some ways, the poster child for what can happen to a trout stream if you don’t protect water quality in its tributaries. Two defunct mercury mines in one of its lower tributaries have leaked so much heavy metal residue into that part of the drainage that the State of California advises people not to eat any fish caught in Lake Nacimiento.

Thank goodness the Naci upstream of the military reservation doesn’t have such water quality problems. That’s why it’s still suitable as trout habitat and provides fishing opportunity. This stream is an improbable and limited fishery. For serious anglers it’s barely worth the drive. But it is a good local resource that deserves to be sustained.

My wife made good on her promise that day. Some disappointments, though, are really not disappointing at all and can be embraced. Others, like loss of water quality protections for a lot of important cold water fish habitat, not so much.

For more information on the Clean Water Rule, and to submit comments on the EPA’s proposed repeal of the 2015 Clean Water Rule, go to standup.tu.org.

Sam Davidson is California/Klamath Communications Director for Trout Unlimited. He lives next to the Carmel River, a once-proud steelhead fishery.