By Mark Taylor

Back when we were enjoying an exceedingly mild February, plenty of friends were confident spring had arrived early. I knew better and, sure enough, March has been a lion here in Virginia.

With actual trips to the river pretty much on hold due to snow and cold, I’ve instead been living vicariously through others.

There is no shortage of ways to accomplish this. Go to “YouTube” and search for “streamer fishing trophy brown trout” and you’ll find enough video

s to keep you occupied for days. Some of them are even good.

s to keep you occupied for days. Some of them are even good.

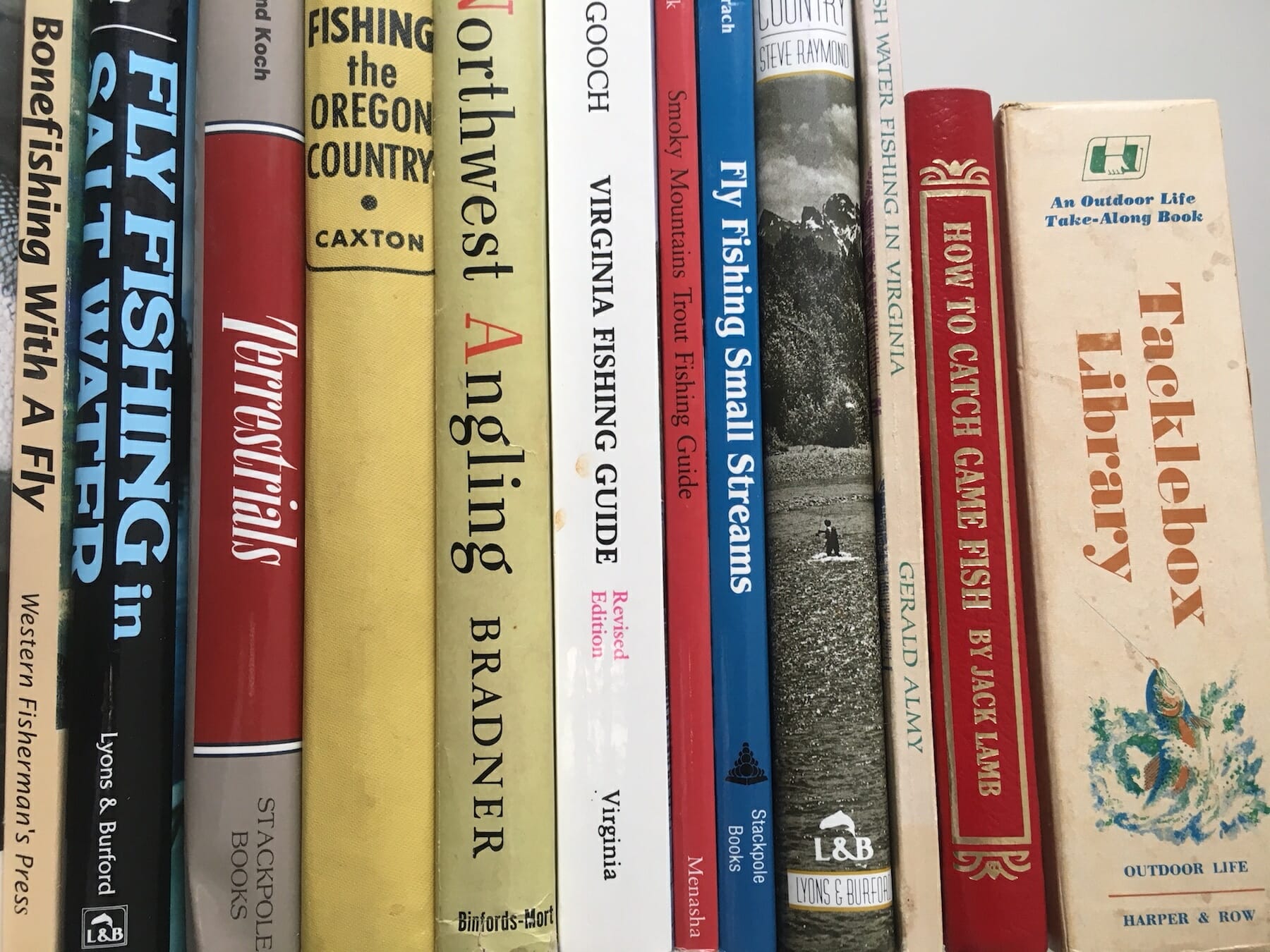

But reading is still my thing. Even as we progress deeper into the Short Attention Span Era, plenty of writers are putting out great stuff, in print and online, including right here at TU.org. While I’m constantly adding current books to my collection, I am also drawn to older books that I find at used book stores and even antique shops.

Vintage volumes not only appeal to my nostalgic leanings, they include practical, how-to information that still applies today.

Most importantly, many old fishing books — particularly regional guides — provide historical context into what, in many ways, were not the good old days.

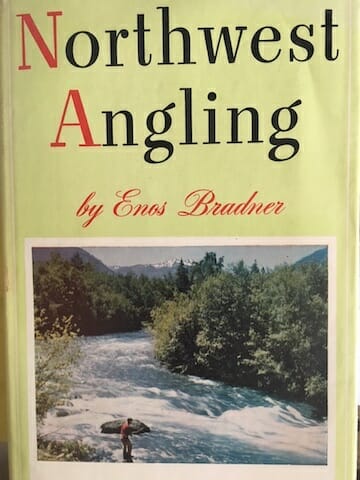

This discussion can’t get too far before one has to decide what actually constitutes vintage. I don’t think anyone would argue against Enos Bradner’s 1950 book “Northwest Angling” or Francis Ames’ 1966 book “Fishing the Oregon Country” being considered vintage or even antique.

But what about something like John Gierach’s “Fly Fishing Small Streams” from 1989, or Steve Raymond’s “Steelhead Country” from 1991?

When you think about how much things have changed over the past quarter century — both in the world and in fishing — I think it’s fair to say any book older than 25 years can be slotted into the vintage category.

Rivers have changed and fishery dynamics have changed with them. But individual wild fish, though fewer in number in plenty of instances, haven’t.

Fifty, or 70, or even 100 years is really just a blink in evolutionary history, after all. Trout hold in the same kind of water and feed in the same ways. Flies and approaches that worked then will work now, even if the equipment is more technologically advanced.

I constantly find intriguing nuggets, including effective fly patterns that have been around far longer than I have, and put them to use on the water.

But a recurring message from these books, especially those 50 years old and older, is that the old days weren’t necessarily the good the old days in many ways.

Until relatively recently, rivers were considered tools for man’s advancement. We exploited countless streams out of ignorance and for profit, using them to send logs to mills (above), to drive hydropower turbines, and as dumps for sewage, garbage and toxic waste.

Fish were an afterthought, if they were given any thought at all.

Bradner writes about how, in the mid-20th century, many rivers in the Pacific Northwest were already being decimated by sedimentation from poor logging practices.

Raymond relates the tale about how a massive slide on logged-over land essentially wiped out the wild steelhead run in his home river.

And, of course, it’s hard not cringe at least a little when seeing photos of and reading about anglers creeling piles of wild and native steelhead, trout and salmon.

The man-wrought devastation of natural fisheries birthed a heavy reliance on hatcheries, a model that still persists and one that, due to increasingly troubling funding challenges for state fisheries agencies, is probably unsustainable.

Lessons from the past have helped foster a better understanding of the impacts man can have on our aquatic ecosystems. We know what we need to do to protect and even restore these valuable natural resources and we’ve made some progress in the right direction. Take the Potomac River, where Trout Unlimited has been working tirelessly in the headwaters. Just this week the Potomac Report Card group reported that the river’s health has improved from a D grade to a B in just 10 years.

It has been disheartening of late to see efforts by some to stanch this momentum, to return to an era where profits and exploitation take precedence over care and protection.

Let’s hope this is a temporary blip.

Wouldn’t it be great if, 50 years from now, anglers can read fishing stories and books from this era and think about how much things have improved over the past half century?

Mark Taylor is Trout Unlimited’s eastern communications director. He fishes with mostly modern equipment but with mix of new and traditional approaches in his favorite rivers around his home in Roanoke, Va.