by Chris Hunt

There’s a great little run on the South Fork of the Snake that’s only wadable when water managers lower the river in the fall, after harvest is all but done and the demand for downstream water subsides a bit. During high summer, with the river literally the

potential energy for Snake River Plain spuds, grain and beats, this side channel might sweep a guy away and drown him if he was foolish enough to set foot in it.

But now, in fall, as the leaves are nearly gone from the riverside cottonwoods, this place is made for the foot-bound angler. A bushwhack through the willows, following cattle and moose trails can take a fisher there, if he or she knows the land a little bit. Ducking under willow branches and over others, it’s an adventure in itself, and on a warm fall day, a decked out angler in waders will likely be resigned to the fact that, as evening rolls around and the waders come off, everything is going to smell like … feet.

But it’s worth it. Only a few folks know where this little channel runs, and even fewer know how to fish it. It’s upstream reaches are slower and sexier, as this is where the baetis hatch on cool fall afternoons. Downstream, there are deep pools that beg anglers to pull big, weighted streamers through the green water. Most walk by this middle stretch between the soft water and the deeep pools because it’s always moving and even in the tailouts, the current is random and unpredictable. And that’s OK with me.

It’s also a nymph run, where something big and heavy running near the bottom has a legitimate shot at a toad. It’s Girdle Bug water.

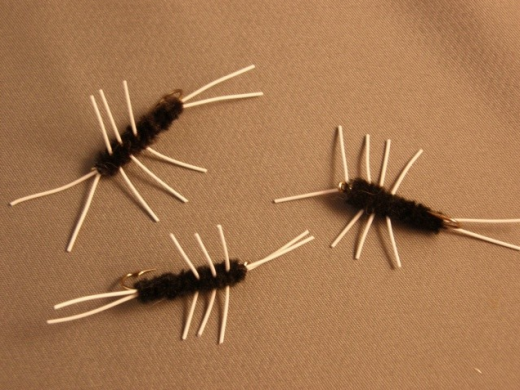

This God-awful fly looks a little like a stonefly nymph and a lot like a fuzzy stick with spines sitcking out of it. I’m not sure why it catches fish, but it does, and often. In this run, where running a weighted two-nymph rig helps get both flies down, the Girdle Bug is a big producer. And every time I bring a fish to hand with this hideous fly stuck in its maw, I audibly ask the trout, “What were you thinking?”

This God-awful fly looks a little like a stonefly nymph and a lot like a fuzzy stick with spines sitcking out of it. I’m not sure why it catches fish, but it does, and often. In this run, where running a weighted two-nymph rig helps get both flies down, the Girdle Bug is a big producer. And every time I bring a fish to hand with this hideous fly stuck in its maw, I audibly ask the trout, “What were you thinking?”

But something else lives here, too. Something decidedly not a trout. Native mountain whitefish, long the subject of disdain among the fishing crowd, perhaps because of its down-turned snout and its relatively plain appearance, also swim here. I’ve long appreciated whitefish in our big Western rivers, not so much because they are particularly fun to catch (even if they are), but because their mere presence is enough to ensure me that the river is generally healthy. A couple of years ago, the South Fork, like the Yellowstone to the north, suffered a parasitic infection that is exacerbated by low, warm water. Unfortunately, the parasite, a microscopic, capsule-shaped critter called Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae, hits whitefish the hardest. While the South Fork didn’t suffer from any significant outbreaks this year (we had a huge winter last year, and the river ran high and dirty well into July with cold, bottom-released water out of Palisades Dam), the Yellowstone took another hit.

For the sake of my river’s whitefish, I’ll take another big winter this year, even if it means I have to enlist my son, largely against his will, to shovel the walks every day.

Whitefish are related to trout, though they’re more closely related to grayling. They tend to be cold-water lovers, and while, yes, their noses turn down, their eyes often look up—I’ve had great winter fishing days catching whitefish on the Henry’s Fork and the South Fork casting tiny Griffith’s Gnats at rising pods of fish.

But here, in this decidedly trouty run, a whitefish will show up now and then, and sometimes it’ll show up with the unholy Girdle Bug stuck in its small jaws. With its solid, silver, heavily-scaled body shimmering in the fall sunshine, I still can’t help but wonder how a fish with a mouth that small could find a way to get a fly that big into its lips. And I look again at the fly that, for the life of me, makes no buggy sense whatsoever and smile.

But here, in this decidedly trouty run, a whitefish will show up now and then, and sometimes it’ll show up with the unholy Girdle Bug stuck in its small jaws. With its solid, silver, heavily-scaled body shimmering in the fall sunshine, I still can’t help but wonder how a fish with a mouth that small could find a way to get a fly that big into its lips. And I look again at the fly that, for the life of me, makes no buggy sense whatsoever and smile.

I’ll look the fish in the eye and simply ask, “What were you thinking?”

Chris Hunt is the national digital director for Trout Media. He lives and works in Idaho Falls.