Since the mid-nineteenth century, the central question of the American West has been:

How much water is there in the region, and how do we best use it?

This question has been a topic of debate for more than the past 150 years, and we’re still trying to answer it now in the twenty-first century. Beginning in the mid-1800s, Euro-American settlers felt it was their duty to develop and control all the water in the West down to the last drop as a part of the Manifest Destiny of the nation. Today, the context around these discussions has changed to incorporate a greater range of uses, needs and values while facing an uncertain future as climate change makes the West drier, hotter and more arid—but the central question remains the same.

Scarcity breeds innovation, and TU is at the forefront of developing creative and innovative ways to address these challenges and answer this question. We do this through the on-the-ground projects we do, advocating for legislative changes that provide new ways to undertake water management and supporting change within federal agencies that incorporates a greater understanding of the needs and opportunities for infrastructure and restoration projects in the West. Our on-the-ground work informs and directs our efforts at the policy and legislative levels. Our partnerships with ranchers and farmers in the West make us a more effective conservation organization at all levels, from putting shovels in the ground to meeting in the halls of Congress.

Each installment of Western Water 101 will be accompanied by a podcast, released weekly. Find the second episode below, and subscribe to get each new episode as it’s released.

Our success and continued reason for optimism that we can create a future that includes water security for people, fish, wildlife and rivers comes from a gradual shift over the past few decades that has brought on increased collaboration and watershed-wide thinking and action throughout the West. While the urban legend that “water is for fightin’ and whiskey’s for drinkin”—that all decisions about water management are acrimonious and unproductive—persists, the reality is that, although division still exists, declining reservoir levels and a growing fear of water stress has brought together diverse stakeholders to engage in critical conversations about our water future in the West. These stakeholders work together to find common ground and creative solutions that provide ecological uplift while also increasing watershed-wide water security for agricultural, municipal and recreational human uses. In order to understand this shift, it’s useful to look back at how the water system in the West came to be and why such a change toward mutual benefit for all water users has followed.

A History of Western Water Storage & Development

“A survey does several things,” historian William deBuys wrote in his history of the Salton Sea in southeastern California:

“More than the removal of native people or the eradication of predators, a survey confirms the taming and domestication of space. A reclamation survey does even more: it measures the fall and drop of potential waterways, the quantity of land that might be placed ‘under ditch,’ the spacing and alignment of canals, the location of diversions, headgates, and overflow channels. It provides a blueprint of a closely controlled physical world.”

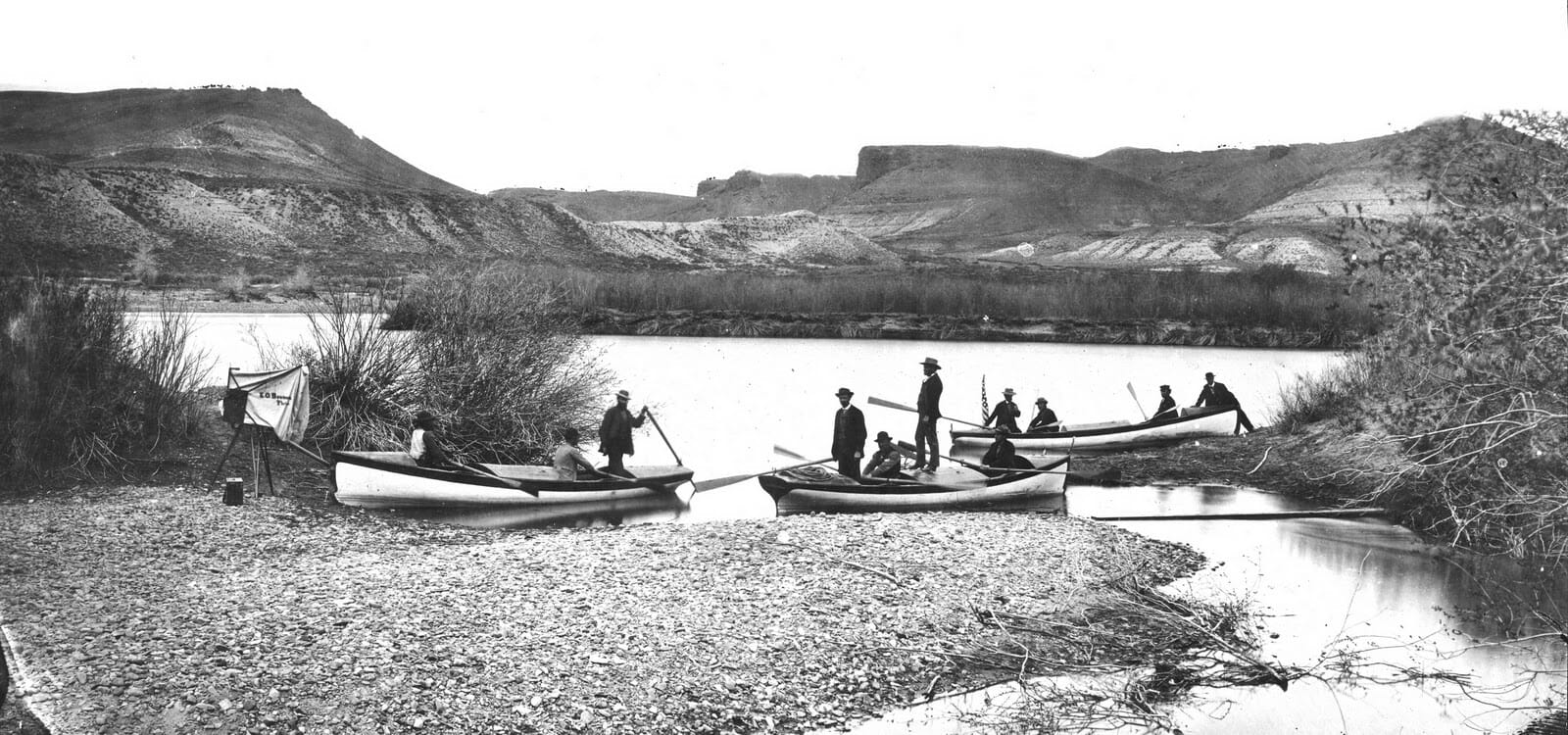

This desire to know the big picture of water in the West—how much there is, how to develop it—was a fundamentally colonial project, undertaken when the first Euro-American settlers sought to understand and survey the western lands acquired from other colonial nations as the United States expanded westward in the nineteenth century.

There of course had been millennia of Indigenous water use, development and management, as detailed in the previous post, but Euro-American territorial expansion depended on the removal and dispossession of tribes throughout the West. Control of the newly acquired territory relied on this and on, as deBuys also wrote, a need by the United States “to claim its land by right of occupation and understanding, believing that it knows, better than its rivals, how to use and settle the new land, how to capture and multiply its riches.”

This desire to know the quantity of water in the West in order to determine how to direct settlement resulted in the first irrigation survey, undertaken by the director of the United States Geological Survey (USGS) John Wesley Powell in 1888 . Though the survey ended only two years after it had begun and without definitive results due to political disagreements, it is an example of the debate that consumed the late-nineteenth century and continues to the present day over how much water the West has and how to use it. In order to put the West’s water to use—and as an answer to this debate—President Theodore Roosevelt signed into law the National Reclamation Act (also known as the Newlands Reclamation Act) in 1902. This piece of legislation is the foundation for western water development: the law funded the construction and maintenance of irrigation infrastructure through the sale of the public land that would be served (or “reclaimed,” in the parlance of the day) by these developments, and it created the Reclamation Service—now the Bureau of Reclamation—to administer these projects.

The Reclamation Act led, eventually, to the construction of the large-scale infrastructure that today dams, diverts, and controls nearly every river in the West, and began with such impressive structures as Hoover Dam on the Colorado River and Grand Coulee Dam on the Columbia . Both dams were flagships for the era of big dam construction, which ran from the early 1930s to the early 1970s and included Shasta Dam in California, Glen Canyon Dam in Arizona, Flaming Gorge Dam in Utah, and Owyhee Dam in Oregon. Throughout the twentieth century while these dams sprung up in rivers across the region to supply the ever-growing population, water managers, politicians, and regional developers continued to ask the same question: How much water is there in the West and how can we best put it to use?

Columbia-Pacific Northwest Region

But in the post-World War II era, with a boom in outdoor recreation, there were a greater number of interests asking that question who wanted to know what role recreation, the environment and other uses played in answering it. The construction of big dams tapered off in the late 1960s and early 1970s with increasing public opposition to large-scale infrastructure that was driven by the modern conservation ethic. This growing debate meant that there were more voices at the table, yes, but it remained an acrimonious topic that still adhered to the “water’s for fightin’” mantra based on an individual’s place in the priority-based water right system and that had defined western development since the nineteenth century.

A Shift in the Conversation

Today in the twenty-first century we’re still wrestling with the question of how much water the West has and how to use it. However, the underlying assumptions about water quantity, beneficial uses and future certainty of supply have shifted due to the sheer number of diversions on the West’s rivers, severe droughts, shifting economies, a desire to include a greater diversity of stakeholders in decision-making and the looming threat of climate change. These factors have combined to cause a shift in the tone and method of the work being done on water management in the West. Collaboration and cooperation now frequently win out over conflict, as stakeholders approach water management from the perspective of the watershed in order to address the big picture issues of water supply and security in a warming, drying region.

Such an approach is not antithetical to the West’s founding doctrine of prior appropriation and other established systems of water governance, but rather a different—and more holistic—way of looking at the challenge of figuring out how much water the West has and how to use it. We can see this in two examples, one in the Yakima River Basin in Washington and one in the Colorado River Basin, which encompasses all or part of seven western states:

Yakima River Basin: The Portfolio Approach

Photo: Department of Ecology State of Washington

The Yakima Basin Implementation Plan provides an example of this more holistic approach and the ability of diverse stakeholders to find common ground. The plan is the result of a work group comprised of agricultural producers, conservation NGOs, the Yakama Nation, irrigation districts and state and federal agencies. This group recognized that fish, farms and people all need clean, fresh water to survive and thrive, and from this grew the goals of environmental conservation, enhanced fisheries and water security. The Yakima Plan does this through a “portfolio approach,” which looks at what the watershed and its residents—human and non-human—need and builds a portfolio of projects that work together to address these needs. These include the construction of fish passages at the Cle Elum and Tieton dams, irrigation infrastructure upgrades throughout the basin to conserve up to 170,000 acre-feet of water annually, increased surface and groundwater storage, habitat restoration for salmon and trout and a flexible water marketing system for moving water supplies throughout the basin. The Yakima Plan provides an example of how diverse interests within a watershed share goals, and how these can be addressed through a portfolio of projects that will provide both environmental uplift as well as basin-wide water security.

Colorado River Basin: The Drought Contingency Plan

In May of 2019, the seven states of the Colorado River Basin and the Department of the Interior signed a collection of drought contingency plans to respond to drought in the river basin that provides water for more than 40 million people in the U.S. West and Mexico and provides irrigation water for more than 5.5 million acres. These historic agreements (collectively known as the Drought Contingency Plan, or DCP) represented the shift toward collaboration and cooperation as the basin confronts a future that is predicted to be warmer and drier due to climate change—the effects of which farmers, ranchers, recreationists and urban residents are already experiencing. The DCP includes reservoir operation agreements based on reservoir elevation trigger points, a commitment on the part of Lower Basin states (California, Nevada, and Arizona) to a system of water conservation, and an agreement by the Upper Basin states (New Mexico, Utah, Colorado, and Wyoming) to study the feasibility of a demand management program. Together, these plans represent historic collaboration in the watershed, as well as a commitment to finding a way to reach basin-wide water security. While there is still work to be done—including ensuring that Native American tribes have a full and equal seat at the table—the DCP has set the stage for increased collaboration and incorporation of a wider range of needs and values as it moves forward.

Conclusion

TU is actively engaged in working within existing systems and finding solutions to watershed-wide security questions, including the dedication of water to environmental benefits. At TU, we engage in these creative, collaborative solutions and the new way of approaching water in the West in three ways, which we’ll discuss in greater depth in upcoming posts:

- On-the-ground projects that promote both ecological health and water security

- Research into the efficacy of federal agency programs’ implementation in service of agricultural producers, municipal users, and watershed health

- Advocacy for changes to existing and passage of new legislation that focuses on meeting the twenty-first century needs of the West

Table of Contents

Western Water 101

- Introduction to Western Water

- Conflict to Collaboration

- TU’s On-The-Ground Projects & Natural Storage: How Flipping the System Benefits People & the Environment

- TU’s Work with Federal Agencies: How Our Research Advocates for Change in the Bureau of Reclamation

- TU’s Work for Legislative Change

- Wrap-up: The state of our hydrology today in the Colorado River Basin

- Take Action