Welcome to the first installment in a month-long focus on water in the West. Join us on a tour through the history of the West’s water systems and major rivers, as we navigate the challenges of drought and water-scarcity facing the region. We’ll also explore Trout Unlimited’s leadership in finding innovative solutions to long-standing problems.

I’m Sara Porterfield and I’ll be your guide on this journey, drawing on my fifteen years as a raft guide and hundreds of hours in white gloves handling original source material in libraries’ special research collection rooms while earning my PhD in Colorado River Basin history.

Our first post explores the defining features of the West that shape the work that lies ahead of us as a western community.

Though the challenges facing the West in the twenty-first century are daunting, TU works tirelessly to keep the rivers of the West healthy, resilient and able to meet the diverse demands on them. We do this by addressing watershed- and landscape-level change in a multifaceted and inclusive strategy—we work with all stakeholders and water users from municipal residents to agricultural producers to members of the outdoor recreation community. The result of this work is not only better fishing, but a community based on finding collaborative solutions, partnering on on-the-ground projects that provide benefits across sectors and forging creative new ways to approach the challenges of a twenty-first century West.

Each installment of Western Water 101 will be accompanied by a podcast, released weekly. Find the first episode below, and subscribe to get each new episode as it’s released.

So, what are those defining features of the West and how do they shape our work?

While gold medal trout streams, whitewater rafting, agricultural production, and municipal and industrial water use all can be found across the United States (and, indeed, the world) the West—defined here as the eleven westernmost states in the contiguous US—requires a different approach than other regions because of four key issues: aridity, Indigenous water rights, the legal system governing water use in the West, and the large-scale infrastructure that dominates the region’s waterways.

1. Aridity

Unlike the eastern half of the country, the West is dry. Most of the region receives less than twenty inches of precipitation per year, with some exceptions—the coast of the Pacific Northwest, for example, can receive nearly 200 inches of precipitation annually, though even these states include areas that only receive five to ten inches per year. This aridity is the defining factor of the West. It has shaped everything from the legal systems governing water rights to the infrastructure that delivers water to urban and rural residents alike.

The arid nature of the West also means that most crops need irrigation water as a supplement to the rain and snow that falls from the sky in order to grow. Unlike in the more humid Midwest, South and East, irrigated agriculture in the West depends on water moved from its natural course—a river, lake, or creek—through ditches, canals, or pipes to farm fields. This aridity has shaped life in the West for millennia; the Hohokam people of southern Arizona constructed canals to provide irrigation and drinking water in the first millennia CE while life in the region today is predicated upon large-scale infrastructure like Hoover and Grand Coulee dams that provide water and power for entire regions. The perceived lack of water due to the arid and semi-arid climates of the West has shaped American perceptions of the region and therefore its reality; aridity has been seen, by Euro-Americans, as a problem to solve—often by brute force in the form of big dams and large canals

2. Indigenous Water Rights

Indigenous water use predates any of the modern governance and development structures in the West. Tribal use continues today, and tribes have some of the most senior water rights in the region. The Winters Doctrine of 1908 granted water rights in perpetuity to Native American tribes that predate Euro-American water rights, though not all tribes in the West have access to those rights protected by Winters. In the Colorado River Basin, for example, the 29 tribes in the watershed are entitled to about one-fifth of the river’s water supply; however, not all tribes have legally quantified the amount of water to which they have a right, and many tribes lack the basic water infrastructure to be able to use their allocations. Quantifying and settling tribal water rights can help tribes construct and modernize infrastructure, deliver water to their members and restore fisheries and ecosystems where tribes have fished since time immemorial.

3. Western Water Law: The Prior Appropriation Doctrine

Western water law grew out of the region’s arid climate. The eastern United States uses the riparian system, which descends from English common law and is predicated upon an abundance of water as well as not needing to apply water to fields to grow crops. Riparianism works as a sharing system: if you own land along a riverbank or lakeshore, you have as equal a right to that water as everyone else with property along the watercourse, provided your use is “reasonable” and does not adversely impact that of any other water user.

In the West, however, the arid climate led to the development of the prior appropriation doctrine, summarized as “first in time, first in right.” Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century with the discovery of gold and other precious metals in California, Colorado and other western states, miners developed a system that allowed them to lay claim to a certain amount of water and move that water out of its natural course in order to develop their mining claims. Under this system, the oldest rights have priority over more junior rights—in dry years, this means that often only the most senior, or oldest, rights are filled while junior right holders may not receive any water. A prior appropriation right is not tied to the land, so the right holder can move water onto a distant parcel of land and sell a water right separate from a piece of land. While water law is determined on a state-by-state basis, every western state uses a version of prior appropriation law and it is the foundation for all development, use and legislation of water in the West

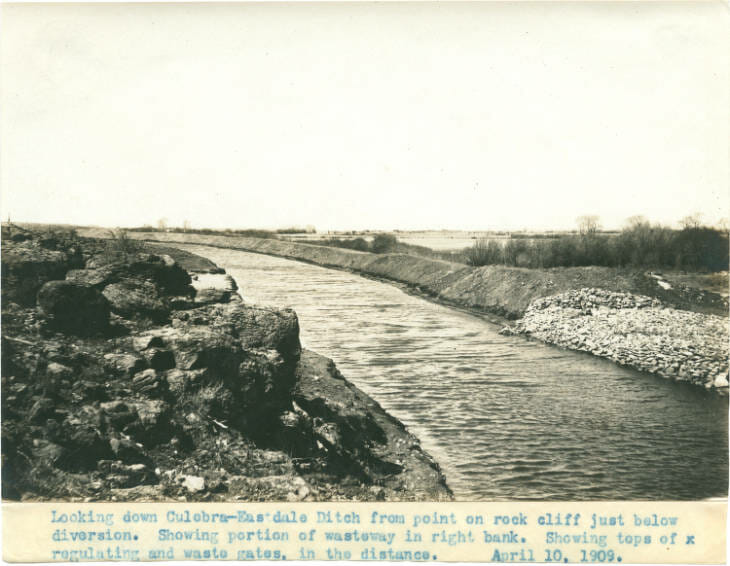

4. Large-Scale Infrastructure

The foundational federal legislation for the development of water in the West is the Reclamation Act of 1902. This law created the Reclamation Service, which is known today as the Bureau of Reclamation and charged it with “the construction of irrigation works for the reclamation of arid lands.” From this authority came the large-scale infrastructure that defines the region today: Dams like Hoover and Grand Coulee, reservoirs like Lake Powell and Lake Oroville, and conveyances like the All-American Canal and the Colorado-Big Thompson Project. We’ll discuss this “plumbing system,” as the western network of storage facilities, canals and reservoirs has been called, and how we can think about twenty-first-century alternatives to these twentieth-century solutions to aridity in the next post.

Challenges & Opportunities in the Twenty-First Century West

These western characteristics have shaped the challenges and opportunities the region faces in the twenty-first century. These include:

A changing climate:

Climate change is making a dry region even drier. The West is thought to already be in a “megadrought,” a prolonged period of lower than average precipitation, which in combination with climate change, is contributing to the aridification of the region. This increasing aridification combined with increasing demand from a growing population has led to uncertainty over the security of water supply.

Equity & inclusion:

For more than a century, the phrase most often used to characterize western water politics was “whiskey’s for drinkin’ and water’s for fightin’.” But beginning in the last decade of the twentieth century, western stakeholders have been working in increasingly collaborative ways and with a more diverse representation of water users at the table. There is more work to be done, but there are many opportunities—and, indeed, a responsibility—to diversify the decisionmakers who have a say in the future of western water.

Ecological health:

The modern environmental movement that began in the second half of the twentieth century helped us start to understand how our plumbing system disrupted hydrologic function of the West’s waterways and the myriad species—including humans—that depend on that function. Now that we have a better understanding of how these natural systems work, we have to try to put that hydrologic function back into place to survive the challenges of the twenty-first century.

Aging infrastructure:

Much of the infrastructure that stores and delivers water in the West is at least a half-century old while some is more than a century old. The age of our water delivery systems presents issues for efficiency, safety and the environment, but it also offers opportunities to think creatively about how to manage water in ways that are more sustainable for people and the environment.

TU is actively engaged in finding innovative solutions to all these challenges and to using the opportunities they present to advocate for and create a more sustainable and equitable future for the West.

Table of Contents

Western Water 101

- Introduction to Western Water

- Conflict to Collaboration

- TU’s On-The-Ground Projects & Natural Storage: How Flipping the System Benefits People & the Environment

- TU’s Work with Federal Agencies: How Our Research Advocates for Change in the Bureau of Reclamation

- TU’s Work for Legislative Change

- Wrap-up: The state of our hydrology today in the Colorado River Basin

- Take Action