In our last post we explored how the management of water in the West has changed over the past few decades from a climate of conflict to one of collaboration and innovation. In this quest for increased water security, improved fish and wildlife habitat and the inclusion of diverse stakeholders in the decision-making process, TU’s on-the-ground projects lead the way in finding and implementing twenty-first-century solutions to twenty-first-century challenges. We are answering the century-and-a-half-old question of how best to manage the water resources we have here in the West with forward-looking projects that benefit all water users—including anglers.

Each installment of Western Water 101 will be accompanied by a podcast, released weekly. Find the third episode below, and subscribe to get each new episode as it’s released.

The West’s water systems depend on large-scale infrastructure to store and transport water. Most of the West relies on big “buckets” for water storage—large-scale dams and their attendant reservoirs on the mainstem of major rivers that deliver water and power to farms, towns and cities throughout the West. The term “storage” has, since the late-nineteenth century, referred in this context to the dams and associated infrastructure that hold rain and snowmelt in reserve for use when the water is needed. This includes big dams like Shasta, Hoover, and Grand Coulee that function on a regional scale, as well as smaller, local reservoirs that ensure water gets to the tap in your home or to a ditch to irrigate a field of alfalfa. Our water systems in the region depend on this big infrastructure both for the water it stores and for how water managers direct and distribute water throughout the system. For this reason, big dams like Hoover and Glen Canyon are integral pieces in western water management and are here to stay.

However, this doesn’t mean that we need to continue building large-scale storage facilities and other infrastructure as we did in the twentieth century. The reality of our changing climate and drying West is that there is not enough water to fill those buckets any longer—but by thinking creatively about how water moves through a watershed we can change the narrative on what counts as “storage” and create a water secure future for people and the environment.

Most Westerners associate “storage” with these twentieth-century marvels of engineering, usually constructed of concrete, steel and other manufactured materials. But the management of scarce water resources and the ability to increase basin-wide water security and create environmental benefits doesn’t have to rely only on engineering and infrastructure. “Natural storage” uses natural hydrologic processes and restoration practices that allow the landscape to act as a sponge and retain water in higher elevations at rivers’ headwaters. Natural storage projects help “flip the system” and focus on distributed water retention in higher elevations—with a multitude of benefits ranging from increased fish and wildlife habitat to drought resilience to the potential for creating fire-resistant landscapes—rather than on building new lower-elevation reservoirs.

The West’s large-scale infrastructure isn’t going anywhere; it’s the foundation of the water system we have and rely on in the region and it makes human life here possible by delivering irrigation water for ranchers and farmers who provide the world with food and drinking water for urban residents in cities like Phoenix, Denver and Los Angeles. But instead of building more reservoirs and pipelines—instead of relying on twentieth-century solutions—we can meet the challenges of a warming climate, a shrinking snowpack and drier summers like the one we had last year by “flipping the system” and employing natural infrastructure projects that provide environmental benefit to create a more secure water supply and a healthier environment in the watersheds where we love to float and fish. TU projects throughout the West are proving that natural storage and other restoration practices can be the twenty-first-century answer to the twenty-first-century challenges we’re facing today.

Projects

TU projects promote water security for all and take a basin-wide approach by providing multiple benefits to farmers, ranchers, recreationists, urban populations and fish and wildlife. These projects can also help restore ecosystem function in rivers’ headwaters and potentially provide natural water storage. The projects below illustrate the diversity of forms these restoration projects can take, from using heavy machinery to remove house-sized placer mine tailings piles in Montana’s Ninemile Creek to working with TU volunteers to install structures made out of natural materials to mimic beaver activity and restore wet meadows in the Sierra Nevada Wasatch mountains.

Golden Trout Wilderness, California

TU California’s Inland Trout Program focuses on headwater meadow restoration as a key conservation strategy for native inland trout species. Over 50% of Sierra Nevada meadows are considered unhealthy and in need of restoration having seen a century of anthropogenic impacts, primarily from over-grazing in the late 1800s. Restored, healthy meadows act as natural reservoirs soaking up spring snowmelt like a sponge, retaining it in elevated groundwater levels, and then slowly releasing it downstream during hot summer months. Meadows recharge our river systems with cold, clean water to support, among other species, sensitive inland trout. Past meadow restoration projects have demonstrated a 30% increase in groundwater retention in floodplains.

A noteworthy project of our Program’s work is on the Kern Plateau-Golden Trout Wilderness Area of the Southern Sierra Nevada to support the recovery of California Golden Trout. The Kern Plateau region is the only native home range of California Golden Trout and has documented meadow restoration efforts dating back to at least 1920. The majority of the Kern Plateau is US Forest Service land and is a prime example of multi-use land management with state-renowned off-highway vehicle trails, wilderness areas, extensive cattle grazing, the Pacific Crest Trail and more. These offer exciting challenges and opportunities for stakeholder involvement in our meadow restoration efforts which currently include 12 prioritized sites across the Plateau totaling over 2,500 acres and 27 miles of tributaries to, or the mainstem of, the South Fork Kern River. We have partnered with the Inyo National Forest, California Department of Fish and Wildlife, Federation of Fly Fishers and leading stream-meadow restoration practitioners to restore these meadows with strong stakeholder engagement from primary user groups such as anglers, OHV users and grazing permittees.

The emerging science of “process-based low tech” riparian and wet meadow restoration is growing increasingly popular and the limitations of working within these wilderness areas provides a platform to test and utilize these methods. Approximately half the meadow sites are also in active grazing allotments that have been passed down for generations and improving meadow forage quality and capacity is one of the many anticipated near-term project benefits. This project has taken a unique landscape-level approach to restoration with a strong emphasis in utilizing techniques that are founded in science and supported by a diverse range of stakeholders.

Chalk Creek, Utah

In northern Utah, TU has been working with private property owners along Chalk Creek to improve water quality and habitat for native Bonneville cutthroat trout for 10 years. As the name implies, Chalk Creek is a naturally erosive and silty watershed. After decades of unsustainable range management, the South Fork of Chalk Creek became known as the largest source of nitrates and fine sediment in Echo Reservoir, one of the Wasatch Front’s primary water sources. TU has led collaborative rangeland restoration through the implementation of rotational grazing programs, irrigation diversion modernization and off-channel livestock watering systems, which have changed the trajectory of land management in the watershed.

However, the historical scars are still on the landscape. Many tributaries have incised or downcut 8-10 feet, carving out entire new stream channels and depositing all that sediment downstream. This has been caused by serial beaver removal in the 1960s to 1990s and bank erosion caused by overgrazing. Moving forward, our most persistent effort will be to try to rebuild the base level of the streams that flow into Chalk Creek. Our primary approach to accomplish this is to construct as many Beaver Dam Analogues (BDAs) as we can in places like Fish Creek. These BDAs work by allowing us to harness the natural stream processes of erosion and deposition to improve instream habitat, reduce downstream sedimentation and rebuild critical floodplains, which promote rangeland and stream resiliency and improve wildlife habitat. As the water is slowed and sediment deposits, the shallow groundwater table associated with the stream begins to rise, rewatering areas of desertification and bringing with it watershed resilience during times of drought, resistance to erosion and downstream sedimentation and improved fish and wildlife habitat.

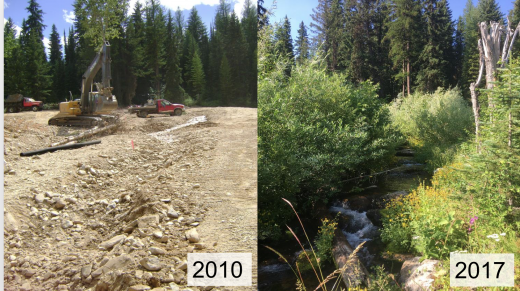

Ninemile Creek, Montana

Beginning in the late 1800s and continuing through the 1960s, Ninemile Creek, a tributary to the Clark Fork River in western Montana, was the target of large-scale placer and then dredge mining. This industrial activity impaired nearly seven miles of Ninemile Creek by creating a “corduroy” pattern of dredge piles and ponds with fifteen to thirty feet of elevation difference between them as well as an artificially straightened river channel. The result of such alteration of the landscape has been the disconnection of tributary streams from Ninemile Creek, as well as dewatering of the stream, changes in natural streamflow, increased erosion, and detrimental impacts on fish habitat and passage.

Because of the scale of change to the natural landscape, restoration in Ninemile Creek requires a different approach than in the previous two examples. In order to create a functional, connected stream system again, TU and partners used heavy equipment like bulldozers and excavators to smooth out the corduroyed topography, relocate the stream from the side to the center of the valley, and restore the straightened river channel to a meandering stream course. Mining activity had so degraded Ninemile Creek that restoration required a heavily mechanized approach to reset the ecosystem; because of the extent of the damage, Ninemile couldn’t heal itself by giving the watershed time and through the “low-tech” restoration techniques employed in the Sierra and Wasatch mountains.

“Resetting” the Ninemile Creek system with large-scale restoration work has allowed TU and partners to then implement low-tech solutions, including attracting beavers to further restore the system and provide habitat benefits. The reestablishment of beaver in the Ninemile’s formerly mined reaches, and their construction of beaver dams and ponds, can help restore natural hydrologic function, including slowing spring runoff and allowing for the potential of higher and colder late season baseflows. This in turn provides improved habitat for native trout species, as well as benefits for the entire floodplain and riparian community. While there are still lots of questions about what outcomes of restoration work can be generalized across geographies, initial data from Ninemile Creek give promising results for the potential to restore this ecosystem.

Conclusion

This kind of on-the-ground work happens in collaboration with local landowners and agency personnel and helps build support for larger-scale adoption of these techniques at the state and federal level. In our next post, we’ll explore how TU works for change in federal agencies and policies to ensure water security and environmental uplift throughout the West.

Table of Contents

Western Water 101

- Introduction to Western Water

- Conflict to Collaboration

- TU’s On-The-Ground Projects & Natural Storage: How Flipping the System Benefits People & the Environment

- TU’s Work with Federal Agencies: How Our Research Advocates for Change in the Bureau of Reclamation

- TU’s Work for Legislative Change

- Wrap-up: The state of our hydrology today in the Colorado River Basin

- Take Action